TOWARD THE END OF HIS LIFE the Czech poet and artist Bohuslav Reynek published a poem that was uncharacteristic in two respects. Its last couple of words are French and Greek. Some poets prosper at the edges of their language, and import foreign words, but Reynek was not one of them. Most of his poetry remains lexically within Czech, with the exception of Biblical vocabulary that had long been domesticated in many European languages over the past millennium (and this is also the case of the Greek word, Lethe, the last in the poem). There are many contrasts between, say, Edward Thomas and T. S. Eliot, and their contrasting approaches to lexicon are indicative of other differences. Whereas Eliot ranges almost promiscuously through foreign languages, Thomas goes deeper into English word hordes, intuiting their connection with the land he walks over and the air he breathes. The French word Reynek uses is lait.

This presents little difficulty even to a reader with no French, and the poem itself provides prompts. In deciding not to use the Czech word mléko (cognate with our English milk), he steps outside his language, into another. Translators sometimes remark that simple words can be the most difficult to translate. Walter Benjamin’s example is how French pain denotes a very different set of experiences from the German Brot. They taste differently, they are obtained in different ways and in different settings; and so, as we break their different crusts, we feel and taste all the aspects that distinguish life in a Francophone community from a Germanophone one. Mutlu Konuk Blasing also emphasizes the way that the phonemes themselves feel differently as we pronounce them, which connects with our somatic history, as our mouths learned the word while eating the food, or in this case of “Rue L…,” drinking the liquid. Reynek obviously sensed that the Czech word for milk was insufficient at this last moment of the poem. As a translator, he had spent a lot of his working life demonstrating that his mother tongue could find terms for anything in French or German. But here that mastery is dropped or found wanting: he does not translate the word, as something, or someone, stops him.

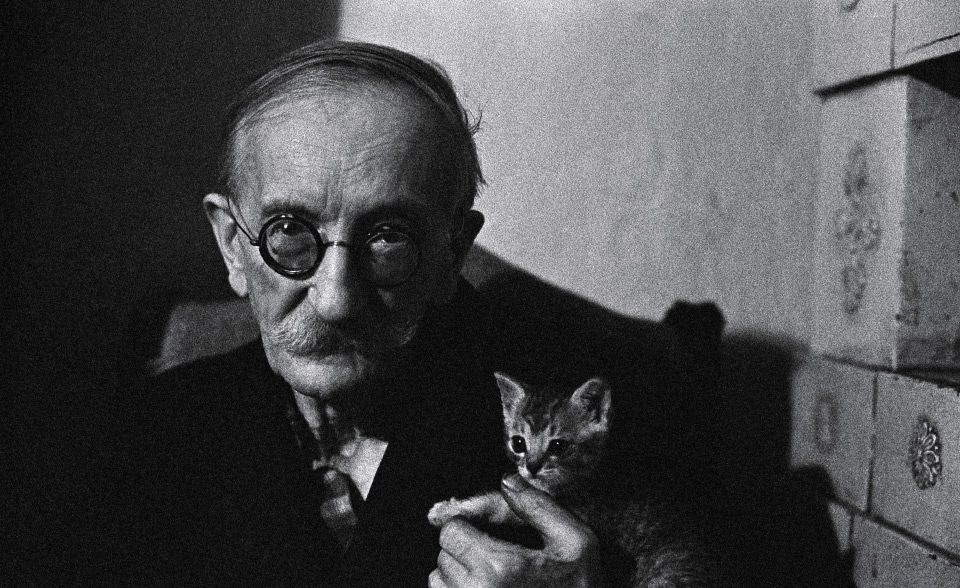

His connection with France was not only literary, and this brings us to the second uncharacteristic aspect of the poem. On March 13, 1926, he married the French poet Suzanne Renaud (1889–1964) in Grenoble. They would later have two sons, Jiří and Daniel, and from the outset of World War II, spent their lives in Czechoslovakia on a farmstead in the village of Petrkov, in the Czech-Moravian Highlands, about an hour-and-a-half’s drive south-east of Prague. His wife pined for her homeland the more she aged. It is a thousand kilometers between their birthplaces, and from 1939 to 1945, and again, from 1948 to the ends of their lives, military and political conflicts made the journey impossible. Yet this journey – whether undertaken or prevented – was constitutive of their life together. Though cosmopolitan in his interests, engaging with French and German poetry in the original, he was always uneasy spending longer periods away from home, even when staying in Grenoble, which he frequently did before the war.

Their children grew up bilingually, and would continue their father’s work of translation and publication of French literature. Reynek translated his wife’s work into Czech and they met when he was translating her first book of poems, Ta vie est là (1922); in English, Your Life is Here. (The subsequent years would give an ironic shade to this title, as it turned out that her life was not, indeed, “here” in Grenoble, but “there,” in Czechoslovakia.) The poem’s title, “Rue L…,” refers to rue Lesdiguières, where the Renaud family had an apartment. While Reynek is one of the most compelling poets of the spirit, exploring the ways in which humans are connected to both the things of this world and of another, it is rare for him to make a poem depend on biographical information like this.

“Rue L…” begins with children wandering through the street, as dawn approaches. They are going for milk and bring their coins with them. The liminal moment between night and day reminds the poet that they are also on another threshold, between life and what comes after. The coins they hold might, in the end, be handed over to Charon, and not the milk man. The shades of the underworld contrast with the whiteness of the life-giving liquid. Reynek concludes by turning away from the children to address his wife, Suzanne, as they pick up some coins also:

We’ll take these on long roads,

entranced, across the lea,

round waters and through woods,

whispering: lait, Lethe…

As with the children, the couple may find both earthly and unearthly uses for the coins. Because they are agèd, they stand even closer to the threshold of life than the children. He also figures a more literal journey, through the lands that separate France and Czechoslovakia. Tolls are paid in specie for different types of journeys.

Reynek was also a Catholic. While much has been written on the cross fertilization of literature in the first decades of the twentieth century with religious beliefs from Judaism to Theosophy, we are less accustomed to Roman Catholicism. For this, we must look to French writers such as Paul Claudel, Charles Péguy, and Léon Bloy, among others. Reynek’s engagement with this intellectual current was profound, and he often adopted its apocalyptic contours in his early career. His home in Petrkov, both biographically and poetically, was underwritten by far-flung places, long journeys, and foreign languages. His life, like that of his wife, although intimately connected with one place, was really everywhere.

His Catholic faith and his farm are the two important frames for both his life and his art. Some poets excel at showing us the complex extent of the world; others look no further than their gardens. Reynek belongs to the latter category: in his greatest poems he remains within the bounds of the farmstead in Petrkov, observing the livestock, the light, and the seasons. His Christian faith makes this space infinite. He finds no easy scriptural lessons in his experience, neither does he impose any. Indeed, on occasion his faith deepens his despair (and then vice versa). For Reynek there is no tension between the physical phenomena he records and the chasms and exaltations of the spiritual life. These are instinct with one another. No ideas but in things? Reynek might well respond: only ideas in things? What about – as another American poet put it – the heavens, the hells, the worlds, the longed-for lands? These too can be perceived in the things of this world, if only one attends carefully enough. His poems are true records of what he saw, and they do not exclude marvels.

A poet like Reynek appears in English, as though out of nowhere, and we scramble for some explanatory context. The first resort of many anglophone readers will probably be the Cold War, and they will be curious about how Reynek relates to, say, Miroslav Holub, and perhaps poets from neighboring countries such as Czesław Miłosz, Zbigniew Herbert, and Hans Magnus Enzensberger. Yet this is of scant use. Simply put, the Czechoslovak regime was not discernible from the window in Petrkov. Not that the authorities left Reynek alone; they nationalized the farmstead in 1949 (though they allowed him and his family to live and work on it). From 1948, Communist cultural commissars had instituted a critical practice of strategic amnesia, designating texts, music, paintings, and films that had no socialist ambitions as non-art. When the regime relaxed somewhat in the 1960s, during the Prague Spring, many poets and intellectuals visited Reynek in the Czech-Moravian Highlands to pay homage. Restitution and remembrance were integral to liberalization, and Reynek, as both artist and poet, was valued by the younger generation, in part because he unwittingly treated Communism in kind, designating it as a non-subject, not important enough to mention in his poems, or to depict in his paintings.

If not the Cold War, then what? “Rue L…” offers another context. Foreignness was integral to this most Czech of poets from the outset. Tradition had it that the family name came from France or Spain. Dagmar Halasová writes that they “based their claim on an entry in a register, where the oldest known Reynek of their family, Jakub, is given as ‘Reňk,’ the inverted circumflex above the letter n a residue of the Spanish tilde. The name itself, they said, then came from the adjective renco, or lame.” Halasová, like most other critics, demurs, but that the family wished to claim such an origin is interesting in itself.

Reynek went to high school in the nearby town of Jihlava, or in German, Iglau. Whereas the present day Czech Republic is monoglot, up to 1945 it was more cosmopolitan, and one contributing factor was that German was the first language of over three million people (almost 30% of the Czech and Moravian population), known as Deutschböhmen, or Sudeten Germans. Jihlava was a predominantly German-speaking town, with a large Jewish community. In 1914 Reynek began working with Josef Florian, a publisher with modest means and large ambitions. A Roman Catholic also, he was drawn to French contemporary writers (he was also the first to publish J. M. Synge and W. B. Yeats in Czech). From the small town of Stará Říše, he commissioned translations, often by Reynek, and published the works in fine editions that frequently amazed French authors when they received copies, with exotic frank marks, in the post.

He was not the only Czech publisher intensely interested in foreign writers, and many of these translations had a transformative effect on Czech literature in the period. Having long engaged with German-language writing, Czech authors were renewing their interest in France, from the Catholic conservatism that Reynek and Florian were involved with, to André Breton, whose Prague connections would later play an integral role in the history of surrealism. In the 1920 and 1930s, Reynek himself translated works by Paul Valéry, Francis Jammes, Georg Trakl, Jean Giono, Charles Baudelaire, Paul Claudel, Charles Péguy, Rainer Maria Rilke, Jules Amédée Barbey d’Aurevilly, Adalbert Stifter, Victor Hugo, Marcel Schwob, Charles d’Orléans, Georges Bernanos, Léon Bloy, Jean de la Fontaine, and Paul Verlaine, among many others. It was an extraordinary achievement. Naturally, his engagement with some writers was deeper than others, and, as critics agree, Reynek came into his own as a poet in this period, with the publication of Lip by Tooth in 1925.

Perhaps he found himself through others; perhaps he needed to hear strange sounds in German and in French in order to discover a way of writing in Czech. Radek Malý, in The Stories of Poems and Their Translations (2014), remarks that Reynek was not purely a servant of other authors in his translations, but left the unmistakable imprint of his own poetic personality on the work. Translation theory has long argued about the ethics of such exchanges, and there is something suspicious about writers using foreign texts as occasions to flaunt their own particular styles, on occasion without knowledge of the source language. Here we have a different phenomenon, as the style and imagination of the poet-translator is expanded by the foreign materials, even as it pushes back against them.

Malý follows the remarkable path of translations of Arthur Rimbaud into German, and their subsequent influence on both German and Czech poetry. These translations enjoyed huge success and Georg Trakl was their ardent admirer. Karl Klammer, the translator, took many freedoms in phrasing and image; the versions were often riffs on Rimbaud rather than literal renderings, and these affected Trakl’s work directly. This was striking, as Trakl had good French and could have read the originals. Next, Trakl is translated into Czech by Reynek, often preserving Klammer’s coinages. Through them Trakl became one of the most influential foreign poets on Czech poetry in the period between the wars. Malý remarks that “it is paradoxical that what readers today perceive as motifs and metaphors specific to Trakl in many cases come from Rimbaud, or rather from Karl Klammer and the way that he translated Rimbaud into German.” This leads him to the conclusion that translators of poetry are not always neutral mediums, but can initiate and inform new relations between and within traditions. In English, though we have some experience of foreign influence on the language’s poetry (though not as extensive as most other European languages), we overlook the role of the translator. In the case of most Eastern European poetry, this is justified, given their relatively small creative input (Holub is a good example of this). On closer inspection, we see that translators, often unacknowledged and uncredited, are important nodes in the translingual networks that make up the European poetic tradition, contributing to its themes and contours. At home in Petrkov, tending to his goats, observing the snow on the yard, the cattle in the byre, a long way from Prague’s cafés and bars where writers worked out their differences, Reynek stood at the very centre of this continental system.

Klammer’s involvement, the extent of its influence unacknowledged prior to Malý’s study, is an index of the deeper and wider patterns of what is sometimes referred to as World Literature. This term is too large for our present purpose; the European zone is sufficiently capacious and labyrinthine. It is a centuries-long conversation across borders and languages, intense in some directions, slack in others, exchanging these valencies from decade to decade. Because English has been a lingua franca for almost seventy years now, and because it has a good chance of maintaining that status for a few more decades, we tend to miss these kinds of conversations, even though they were constitutive of our own poetic tradition, for instance in sixteenth-century sonneteering.

Martin C. Putna has described the different forms and modes of Christian literature in Europe in the past centuries, in order to define the Czech approach in the early twentieth century. In the English tradition, two of the finest poets of religious poetry are Gerard Manley Hopkins and George Herbert. Both are at the heart of the English tradition of devotional poetry; both are intensely engaged with form. Hopkins on occasion pushes words to their limits. Donald Davie remarked that such contortions damaged the poems, but others have not agreed; for instance, Seamus Heaney found in Hopkins expressive possibilities that opened him, Heaney, as a poet. Similarly, the critic Miroslav Červenka has referred to the “cloddishness,” or “ineptitude” of Reynek’s language, not as negative criticism, but rather as a means of identifying Reynek’s rejection of poetic speech that has been smoothed and sleekly shaped by the current in the centre of the stream. Putna elsewhere identifies this as Reynek’s deliberate turn from both “text-book prosody and the avant-garde” to embrace a linguistic knottiness and naivety. Other poets who come to mind are Robert Frost and Edward Thomas, for their use of form and the rural setting of many of their poems.

But comparison only gets us so far, and the similarities observed can often be of an aleatory nature, too general to be illuminating, as though we claim a similarity between the practice of crystal gazing and the game of soccer because they both use a ball. Roman Catholicism, as a common factor between Hopkins and Reynek, is different from this, as it is a shared European heritage, both a framework of belief and a tradition of cultural artifacts. The same holds for the tradition of European lyric poetry, some of its skeins tweezed out by Malý above. By remembering how many foreign debts anglophone poetry has accrued over the centuries of its existence – from Greek, Latin, Italian, French poetry among others – we are reminded that a poet like Reynek, who seems to emerge from a faraway country of which we know little, is part of the same tradition, of which English poems are only one part. This is lyric poetry of a type in which the poet uses certain patterns of rhyme and pacing that many previous generations have. It is a way of finding likenesses in both words and the world, or sometimes impressing phonic likenesses on disparate experiences, and savoring the phases of that difference.

Successful poetry translation – and Reynek was very successful – reminds us of this common European tradition. Rimbaud arrives with éclat in German, transforming Trakl, who then is brought into Czech, helping Reynek at a key moment in his poetic development. Reynek now approaches English, trailing these particular clouds from French and German skies, as well as Latin, Italian, and of course Czech. Successful poetry translation often also hides the work of conveyance, the long hours spent learning another language, and then the months and years spent becoming familiar with alien airs and graces. We overlook translators in our enthusiastic discovery that we have much in common with a poet from another language. This is what Reynek did when rendering Jammes, Trakl, and many others into Czech, and it is also what he did in his original work, as he mostly excludes the traces of foreign, as I mentioned at the outset, rejecting a macaronic modernist technique in favor of the unadulterated mother tongue.

This is why “Rue L…” is such an intriguing poem, as it hints at the long journey that translation requires; it also indicates that translation not only entails the transfer of literal content and rhymes from one language to another – a kind of advanced crossword-puzzle work – but is connected with friendships, marriages, children, systems of belief, and personal fates. Milk is the first thing that most human beings taste; at the same time they also taste the flesh of another person. Soon after this, they learn their mother tongue, which is both a symbolic code and a matrix of physical sensations. We are physically situated in a language – the coding carved in our oldest bodily memories. No matter how fluent we become in other languages, we are anchored thus in our first words. The word lait remains recalcitrantly untranslated, in acknowledgement both of his wife, as well as the limits of his own mastery as translator.

— Justin Quinn

_______________________________________________________________________

This is an edited version of an essay that will appear in The Well at Morning: Selected Poems 1921-1971, by Bohuslav Reynek, translated by Justin Quinn.

_______________________________________________________________________

JUSTIN QUINN is an Irish poet, critic, and translator who has lived in Prague since 1992. He works at the University of West Bohemia and is the author of several studies of twentieth-century poetry, most recently Between Two Fires: Transnationalism and Cold War Poetry. He is a frequent contributor to B O D Y.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more by Justin Quinn in B O D Y:

Essays:

Review of Steph Burt’s THE POEM IS YOU in the April 2017 issue

Review of Joseph Massey’s TO KEEP TIME in the January 2015 issue

Review of Joshua Mehigan’s ACCEPTING THE DISASTER in the January 2015 issue

In Memoriam for Dennis O’Driscoll in the February 2013 issue

Translations:

Translations of two poems by Bohuslav Reynek in the March 2017 issue

Translations of three poems by Wanda Heinrichová in the November 2015 issue

Translation of a poem by Jan Zábrana in the November 2014 issue

Poems:

Poem in the November 2014 issue

Three poems in November 2013 issue

Translation of a piece of short fiction by Petr Borkovec in the October 2012 issue

Two poems in July 2012 issue