I first saw delphine hennelly’s work in person several month’s ago at her MFA thesis at Rutger’s University art gallery. Although figuration in painting has come back into fashion, her work stands out by decisively presenting you with a system of signs and symbols that include the figure, while forgoing the more blatant illustrative function of such elements. To learn more about the motivations behind her cryptic and engaging work, I had the opportunity to interview her shortly before the completion of her MFA. – Jessica Mensch

B O D Y: In your most recent series of paintings you’ve taken the step of incorporating repeating forms and motifs into your compositions. Can you talk about this?

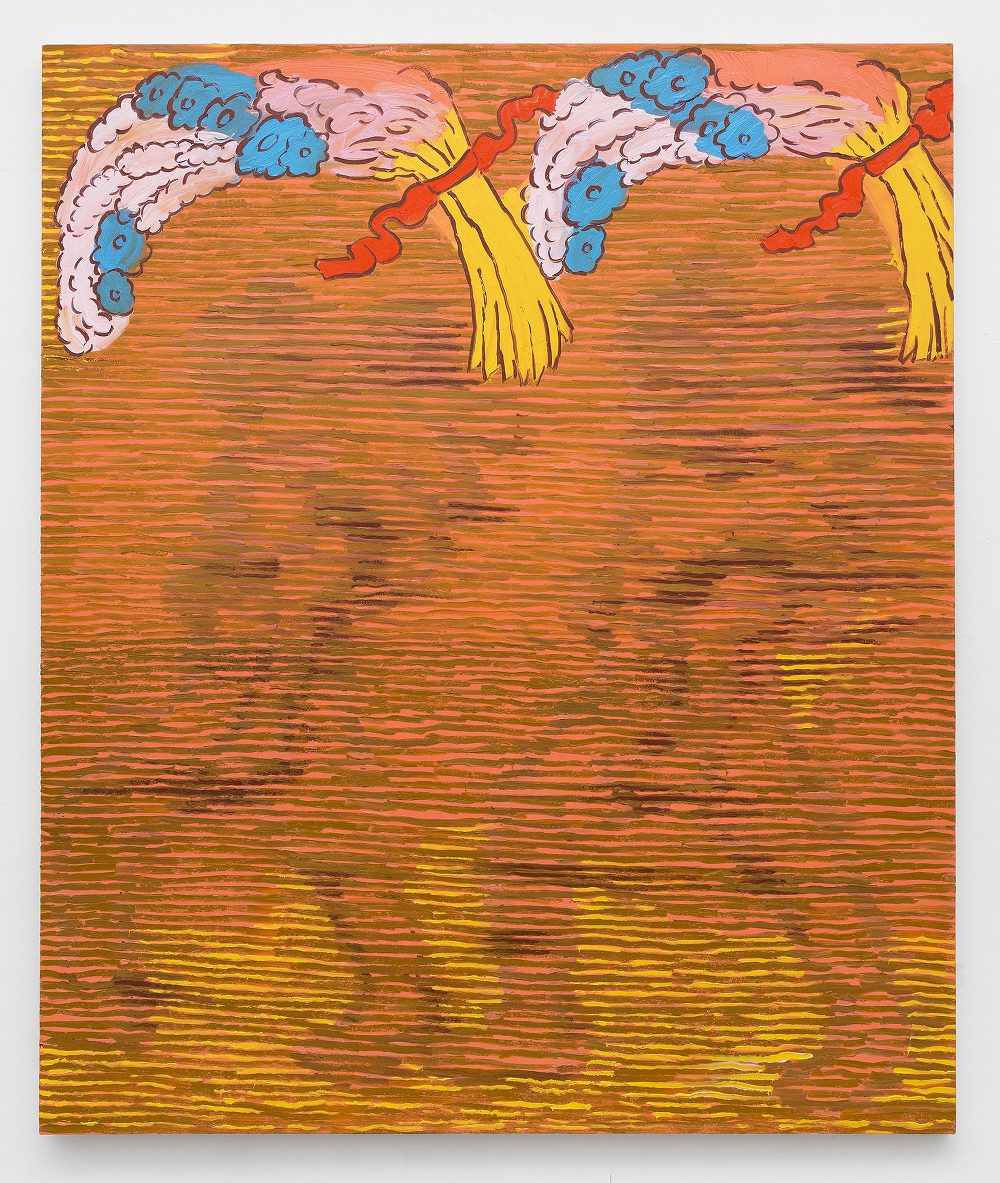

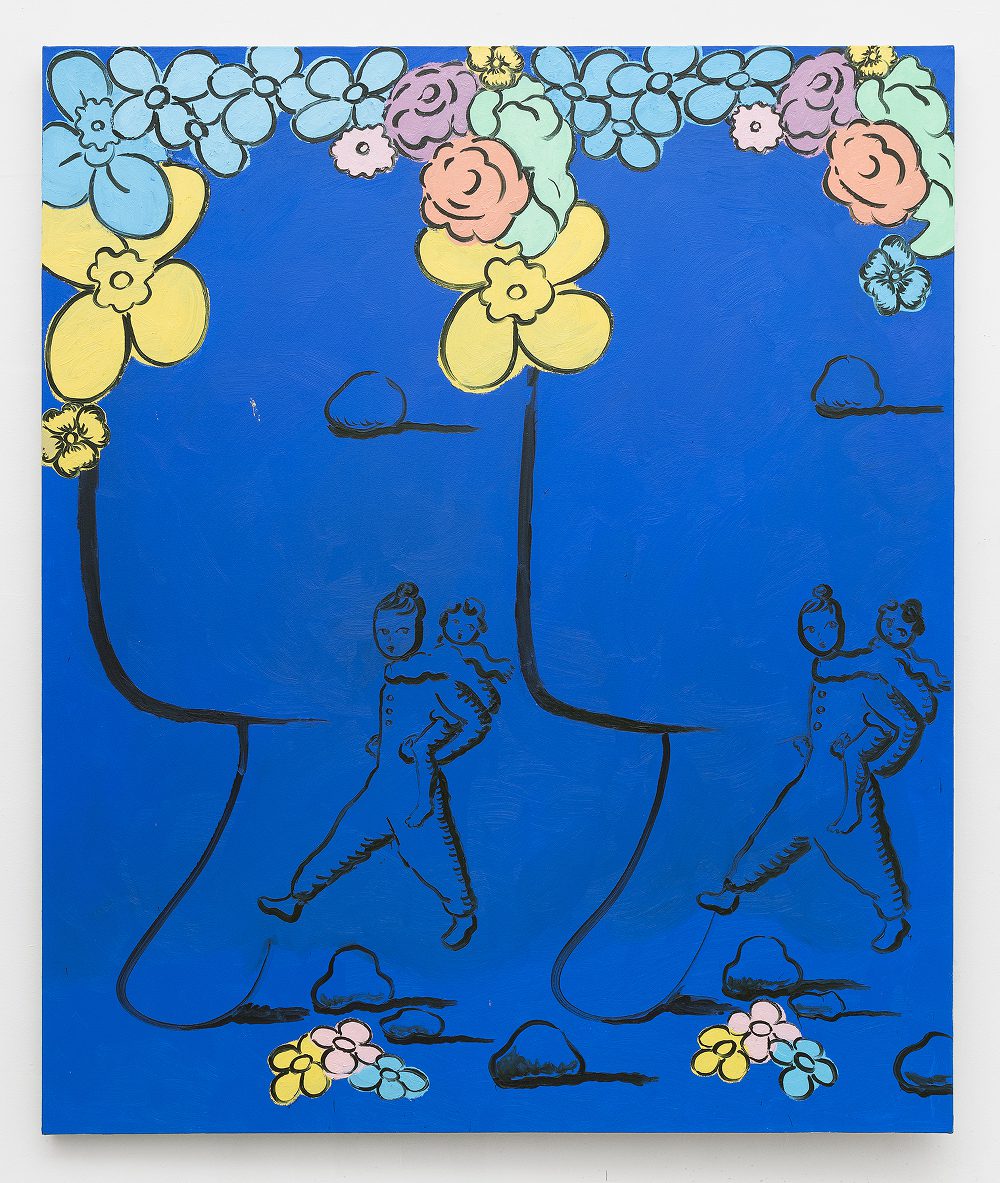

Delphine Hennelly: I’ve sort of always been interested in patterns as a compositional tool, but last summer I had a break through with a painting I did after the Orlando shootings. It’s titled Actaeon/Orlando. As political ramifications unfolded in the aftermath of that tragedy, I became particularly interested in the various defenses for gun ownership — one being, hunting. This seemed so retrograde and pompous to me that it spurred me to paint the image of The Hunter. I based the painting on Raoul Dufy’s textile design, La Chasse, and couched the story of The Hunter within Greek mythology, emphasizing the tragedy of a man burdened to fall prey to the outcome of his own desires. The doubling or patternization of the figure within this context made sense to me in that it implied a continuum and a repetition in time. By eliminating a large figural element, the pattern became integral to the formal structure of the composition and I was freed up, in a sense, to get away from the figure/foreground issue that feels technical for the most part, and actually kind of boring. The takeaway from that painting is that I became fixated on having a double figure as a means to depict a sense of moving through space. I also felt that once I began doubling my imagery, multiple numbers of this imagery were insinuated. I also like to have a continually rotating roster of elements as a kind of paint catalogue. For example, I’ll have a flower motif, a figural motif and a rock/pebble motif from which I can pick and choose from where I see fit.

B O D Y: So then are you developing your own system of signs?

Delphine Hennelly: Yes exactly. It’s like building a lattice or framework from which to work.

B O D Y: So the viewer, becoming familiar with these signs through seeing a succession of your works, begins to participate in the narrative – or rather uses these signs to speak about and understand your narrative? Actually, I’m hesitant to call what I’m seeing ‘narrative’ — do you see these recent paintings as having a narrative?

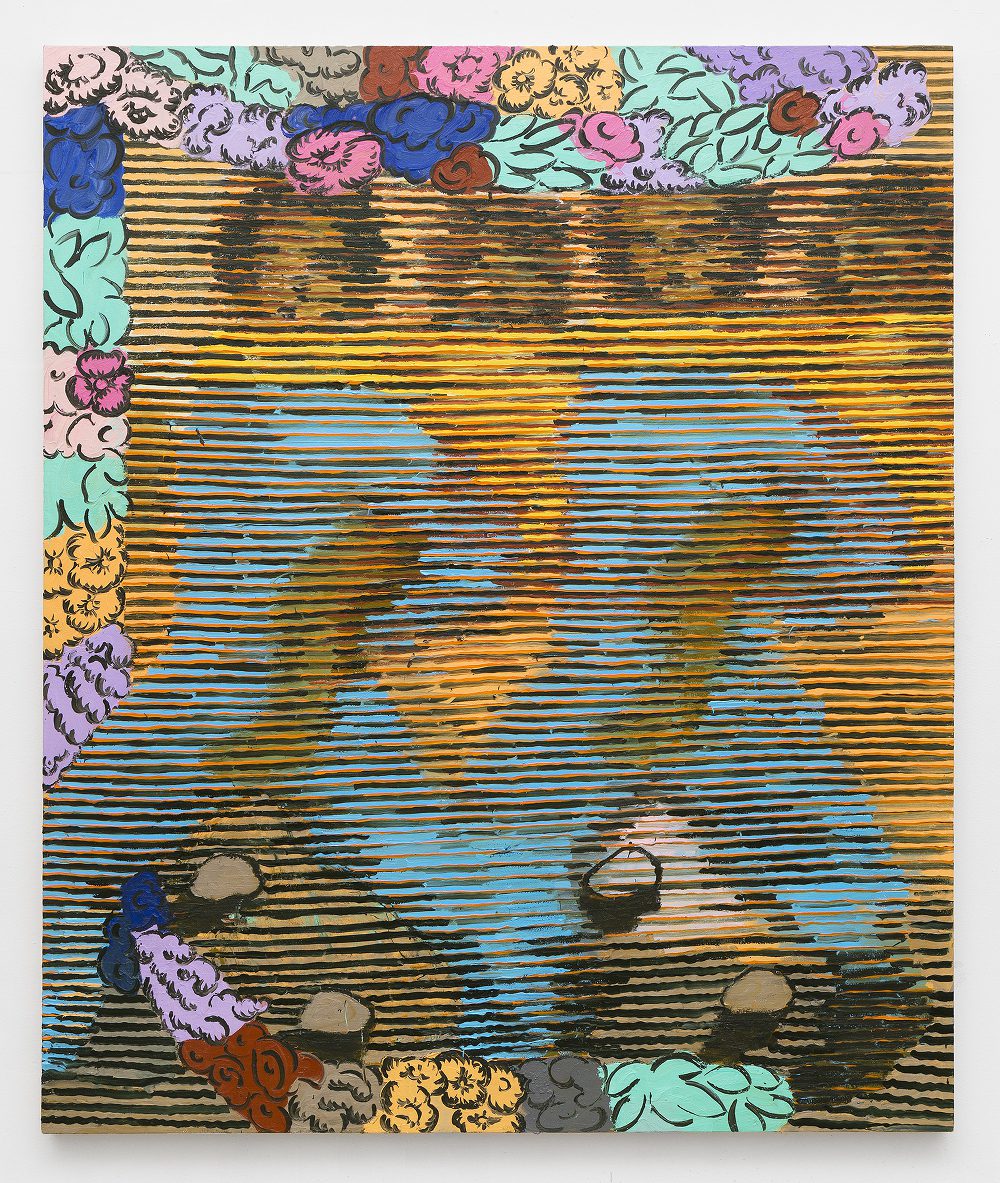

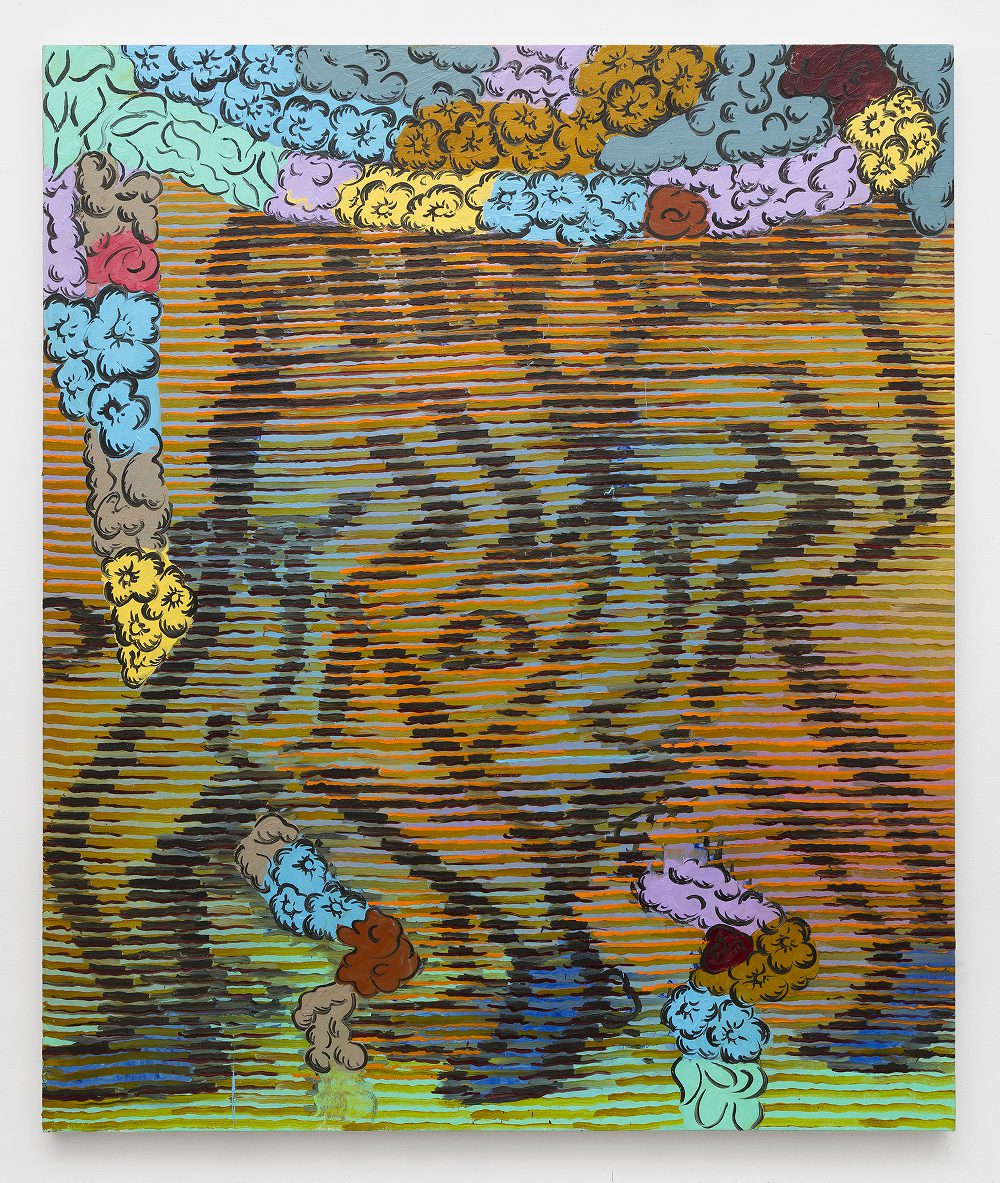

Delphine Hennelly: Well you’re right to hesitate about the narrative. I don’t see myself as a narrative painter. A lot of the motifs I use are chosen over long periods of time and are often inspired by elements found in other paintings. For example, the rock motifs I use are taken from the rock motifs that often appear around the foot and upper edges of paintings, tapestries and engravings from the Renaissance. I’ve always been fascinated by the rocks in Manet’s painting, Dead Christ With Angels. As a viewer, I’m interested in the edges of a work — specifically the attention that is given to those parts. The flowers I paint come from the same place — they’re often the part of a painting that’s there to decorate. However, I do think they also act as a seductive element, and in my work, I use their innate allure to distract the viewer from the plight of the figure. I’ll often use a stone motif to lock a picture plane in place — like paperweights. In general, the motifs that I appropriate I choose because of their formal references. Of course I do feel the motifs garner meaning, but it is only through their repetition that this comes out. I guess in some ways I’m interested in imbuing the meaningless with meaning, or rather, finding ones presence in the everyday. I do feel like there is a story in my paintings but on a larger scale then an A-Z narrative that’s limited to a single work.

B O D Y: At this point, is your story definable?

Delphine Hennelly: Well, I don’t know if I know how to answer that directly, but I can speak about some of my thoughts surrounding my imagery – one being the present day migrations of peoples and growing diaspora’s due to worldwide destabilization. This reality forms the basis for much of the politics in the foreground of my most recent series. In this regard, imagery from textiles and ceramics provided me with a huge source of inspiration – particularly because I associate these objects with domesticity and bourgeois comfort. I transformed this found visual material into visual tropes and juxtaposed them with the image of a figure in motion. For me, this implied a sense of destabilization, displacement and uprootedness. So for instance, my flower garland motif that is seductive, overtly decorative, recognizable, easy and comic-like, I clashed with the marching action of my foregrounded figures. In a sense, this is a reflection on how walking can be a form of resistance or protest. A constant question for me while making these paintings was: ‘is the figure moving towards or away from a life of comfort.’ As a result, I became fixated on the direction my figure was striding in – specifically, left. One effect of this was that it gave a counter clockwise motion to the movement. Also, because we read from left to right in our western culture, the gesture of the figure walking towards the left, for me, implied an exiting of the figure, or viewed another way – a gesture of resistance.

Tapestries and screen technologies also became meaningful associations for me in this series because they’re unique apparatus’ for viewing an image. In tapestry, the act of replacing a brushstroke with a thread, coupled with the unique manner in which the image can decay, is visually interesting to me. The effect of looking at an image worn by the ages is a quality I wanted to replicate, so I painted breaks in a linear pattern which resulted in an image that began to look both digitized, glitchy and worn with wear and tear. These painted tapestry weaves ultimately began to take on the appearance of having a mediating element, like a digital screen. They reminded me of rasterized images or interlaced videos with a shallow depth of field. For me, the doubling of the marching figure also indicated a glitch-like movement, similar to what one would see on a digital screen.

Also, and this goes along with the idea of repetitive motifs – I’m interested in the effect of negation which happens when a figure is repeated. By negation I don’t mean erasure, but rather as a means of neutralizing heavily gendered images of motherhood. I really felt that I needed to avoid the saccharine and sentimental in this respect, so it was imperative that I resist any easy allusion to the Madonna and child of Christianity. Simultaneously, the binocularity of the “double vision”, (i.e. the repeating figures), implies a self that is divided and/or the presence of two separate psyches – one of the mother and one of the child. Also, the feminist comparison between the self that is projected and objectified, and the self that is hidden or private is also something I hope to allude to. I often reflect on what the female form in defiance of this subjugating doubling could be. So, a literal representation of this psychological state felt like a necessary place to start.

B O D Y: The image of a mirror often appears in conjunction with the double image of a woman and child. Can you tell me about this?

Delphine Hennelly: I have often used the mirror as a nod to the art historical viewer looking in but not being seen. The mirror in its lonely objecthood blankly reflecting back seemed like a funny idea to me. It also seemed like an obvious way to send an invitation out to the viewer to enter the image as it kind of doubled as a window. In the later paintings I eliminated the mirror motif entirely but in the first iterations of the series I was intent on working out an image using a set of improbable variables. In these first paintings for instance, I appropriated the whimsical and decorative style of painted Delftware plates and contrasted this with a diminutive figure, who was journeying through this stylistically bucolic setting. The superimposed giant mirrors were a way to turn this figures journey into a fable. At some point I also saw the mirrors as large cartoon eyeballs with tear drops, but I didn’t end up developing this. The paintings eventually took a different turn. In many ways I am not that interested in having the paintings be fairy tales and they were starting to look that way with the large cartoon mirrors. Mostly, the mirror is interesting to me because it pushes the viewer to reflect on their identity. A mirror is usually always about oneself, not really the other.

B O D Y: Does the double image of the mirror partnered with the double image of the woman and child refer to the vision of two eyes — each eye seeing it’s own image? Or does this refer back to your idea interest in repetition?

Delphine Hennelly: Yes! Totally. It’s hard to talk about mirrors without making a pun, but the word ‘reflection’ comes to mind. I want people to think about the word ‘reflection’, whether it be the thought – “I see no reflection”, or “The mirror is epitomizing this thing I’m doing which is reflecting on this image”. I like the ever folding in, ever self-referencing pattern of this set up. It’s also funny when the whole image morphs into a face that is looking back at you, with big, dead end eyes. I like it when the meaning of things flips. So for example, a window let’s you in, but a mirror pushes you, back to you. I was also looking at a lot of Guston and was trying to think of ways of making objects the main characters of my paintings. These were my first paintings where I was getting away from the figure/foreground relationship.

B O D Y: I was just going to ask you about that. You said earlier you were attempting to depart from the figure/foreground issue because it felt both technical and uninteresting at this point. How does the graphic or cartoonish manner in which you portray the figure in your recent works circumvent this issue?

Delphine Hennelly: I’m not sure I am necessarily circumventing the technical issues of the figure/foreground problem, but the less time I spend worrying about that aspect of my painting, and just get on with the image making itself, the better! I have always been drawn to cartoons, or in other words, the exaggerated quality of an illustrative trope. One aspect I like of cartoons is the flattening of space such that the foreground is no longer something to consider. Also, with illustration one can allude to space and it’s understood as space. The illustrative framing device locks a space into place. One could definitely argue against all this and I am always shifting in my opinion, but that is how I feel right now. I guess what I’m trying to get at is that I don’t want to be held back by being overly descriptive with what I’m depicting. The quicker I can get to the whole picture the happier I am with an image. With figuration this is a constant struggle. Figures demand to be recognizable, descriptive and believable in their placement within the picture frame. The more I can push the limits of this the more interesting painting becomes for me. It’s not so much that I want to turn the figure into an object, but rather that I want to be able to bend the figure to suit the larger, formal problem of composition. Does this make sense? I think I’m actually a closet abstractionist. I really am driven by formalism.

B O D Y: So you walk the line between figuration/representation and abstraction?

Delphine Hennelly: Yes. It goes along with not being that interested in narrative. To get back to your question about the image of the Mother and Child, the women I painted previously were overtly sexual. The mother figure is a reaction to this. In previous paintings my female figures are coy, overt and exaggerated. These figures are a subversive response to the ubiquitous art historical female nude. In contrast, my current paintings depict a female form that has been emancipated from the gender normative expressions of femaleness. My women wear loose, gender neutral, one-piece suits. The front of the suit is flattened – undermining the expected reveal of breasts. And her striding legs are only loosely defined -in this instance, by the shapeless pant-suit that she wears. Her boots are utilitarian in style, which for me indicate a strong intent behind her energetic stride. Vanity does not come into play with these garments — which is funny because the mirror would perhaps imply vanity.

B O D Y: Ok, I see the connection between this formal transition and the change in your articulation of the female image. This makes a lot of sense.

Delphine Hennelly: Just to add, in my ongoing interest in the depiction of the female form, many of my earlier paintings are pastel colored, suggesting a playful levity. I would also say that the proclivity of gendered pastel colors has always been of interest to me, and is something I consider when working to subvert gender normative tropes. These newer paintings depict a departure from the pastel color palette of my previous work. For example, blue pervades these newer paintings, and is always the color of the clothing of the central female figure. For me, blue is a utilitarian color, the color of workers clothes and denim.

DELPHINE HENNELLY currently has work on view at Standard Projects at 111 S Nash St, Hortonville, WN. She also has a series of drawings in a traveling exhibition titled “Got it For Cheap”, curated by Charlie Roberts.