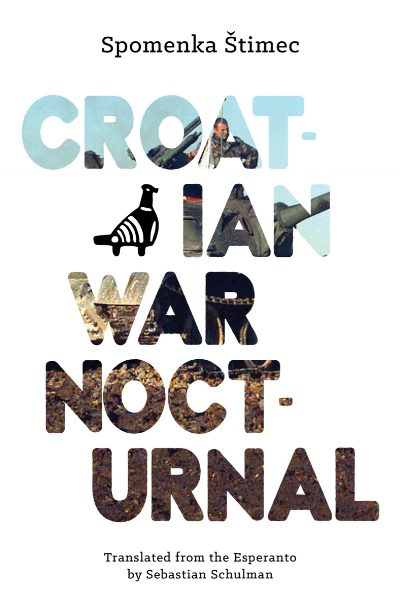

CROATIAN WAR NOCTURNAL

(an excerpt)

Croatian War Nocturnal

A novel by Spomenka Štimec

Translated from the Esperanto by Sebastian Schulman

Published by Phoneme Media

Recruitment

Today my brother was called up to the front.

I shoved my hand in the mailbox and took a look at its contents. A very meagre harvest today—only newsletters. From France came Franca Esperantisto whose front page invited the reader to come plant trees together. On another bulletin there was a stamp bearing the image of the Olympic flame. The lead article was a report on an amusing cabaret that had delighted its audience. In the accompanying photograph, the ladies wore long skirts while knights sported melon-shaped hats.

I belong to those who believe that we are waiting our entire lives for the letter that will change everything. As the writer Milovan Danojlić once put it, “Whenever I see the postman coming down the street, I put all my hope in him. Maybe today he’s bringing the great news at long last! Ever since I first became aware of myself, I have been waiting for some sort of redemptive piece of news. The message that will change everything and that will set my life on a new course.” I dug my hand into the mailbox one more time to be sure that nothing else was there.

At the back of the mailbox I found a card on which was written: ORDER TO REPORT FOR MILITARY SERVICE. It was hard not to just stare at it dumbly. Here it was, the day when everything changes. I had asked for a change, had I not?

The army wanted my brother to report the next day at nine o’clock. The draft card covered up the ladies with their long skirts at the evening cabaret. France cabarets its nights away. I was born here, where a different program is in store. A mix of fear and bitterness suddenly overwhelmed me and wouldn’t let me climb the stairs. It was as though I had to carry the whole cast of the cabaret up with me to the third floor. My fingers began to swell, my arms trembled.

My brother and I used to share an address from the time we used to live together. After he moved in with his girlfriend, he didn’t bother to update his address with the ministry of defense. And that’s how the war came to my doorstep.

I imagined him at home, newspaper in hand. When I call, he’ll reach for the receiver, and never again be able to pick up the thread of the article he’s reading. I decided to give him one more hour of peace. I washed my hands for a long time, scrubbing my fingers cleaner than usual. Those fingers that had held the draft papers. The text was the same when I read it again for the tenth time. My brother was expected tomorrow morning at nine o’clock in accordance with his military obligations.

I decided to delay informing him. Let him enjoy life for another ten minutes. I’ll call him in another hour.

Should I run away? Where to? To the nightly cabaret? I belong to those who believe that it is not possible to run away from one’s problems.

I’d already lost him once before. One day when he was four years old, he disappeared from the house. That afternoon we couldn’t find him anywhere. I walked around and around the house calling his name. His ball lay in the yard, but he was nowhere. I wandered the streets, searched every playground, questioned every child. He’d been seen before lunch, but not after that. Nowhere. When my father came back home from work I had to tell him that my little brother had vanished. But how could he just vanish? We went looking together, calling out loudly and hopelessly, visiting every store in the neighborhood. He was nowhere to be found. Father grew very angry. I saw my brother’s tiny shoes in the hallway and my heart shuddered. Between bouts of anger and anguish, I was suffocated by emotion.

My father discovered him later that evening. He was in the basement along with another small friend of his. They had decided to paint the windows in the basement and hadn’t wanted to answer us when we called for him. My brother could tell that the decision to color in the windows was probably something he wasn’t allowed to do. He managed to open the paint buckets, found a brush, and clambered on top of a chair to reach the windows. His friend needed a paintbrush too, so they took a bundle of dry twigs and stuck them at the end of a pole. Their tools didn’t necessarily paint the straightest of lines, but the laws of geometry didn’t hold them back.

He stood there, his striped sweater stained in unwashable green paint, and waited for my father’s tempest of outrage to subside. His friend ran home, palms painted green, while my brother’s chin sank down to his slippers in shame.

No one ever finished painting those windows.

I was so happy that he was back, at home and in the kitchen, but I also felt that I was supposed to get mad at him, at least a little bit. In the family rulebook, it was a great sin not to respond when called for.

“How could you scare us like that?” He lifted his eyes, his feelings hurt, and refused to answer. A sad smile spread across his face recalling that incident with my baby brother. Tomorrow at nine o’clock he will be given a rifle.

Hardly ten minutes had passed. It was silly of me not to have told him immediately. He should make what he wants out of his last free night. I’ll go call him now!

I felt faint. I had to drink some water first. How to start so as not to frighten him? So many of his peers have already left for the front. Some enthusiastically. Some out of a sense of duty. The number of casualties meanwhile continues to climb. But there’s talk now about the end of hostilities and the soldiers’ return. Are new soldiers drafted simply to take the place of their more tired brothers-in-arms? My feet sunk into the floorboards just thinking about wearing heavy soldier’s boots. Cautiously I wriggled my toes to prove to myself that I didn’t have those bulky things on my feet.

My cousin is probably fighting on the other side of the front line. This isn’t just conjecture—why shouldn’t he be there? This is after all a civil war and my cousin has lived in our former capital—now the enemy’s chief city—since the age of six. My cousin could have been called up with similar piece of paper written in a similar language, given a uniform and a rifle at nine o’clock some morning, and shown the truck that would take him westward toward some river at the border.

My brother and my cousin haven’t seen each for several years. One winter at our grandparents’ house they ran one after the other around the table trying to catch each other with homemade lassoes. Grandfather had laid down on the couch for a nap. Suddenly one of the boys ran by and banged him right in the middle of the forehead. Grandfather shot up in surprise and the boys ran off, stifling their laughter. It was up to Grandmother to discipline the troublemakers.

Has this battle between cousins returned? Is it not possible to find a more pleasant way to celebrate their reunion?

The last we heard my cousin went into hiding. He won’t be found. Others will shoot instead. Not much consolation can be found in that.

Maybe I should listen to the news first? I thought. Maybe something serious has happened and I don’t know about it yet.

No, I won’t hear the life-changing piece of news on the radio. That piece of news was already here.

I dialed his number. His girlfriend picked up. I told her that I had some bad news. She didn’t understand. She didn’t want to understand. I had to repeat the horrible information twice. My brother had just stepped out to get a fresh loaf of bread from the store.

In the meantime, I had to try and work as though nothing was going on. On my desk, a book of Korean folktales lay open to the story of Kyonu and Jingnyo. The two lovers were separated, a punishment for disobeying the orders of the Sky King. With the help of the magpies the lovers reunite one day a year, every year. A galaxy of stars, great and deep, divided the lovers.

Where were the magpies now?

Perhaps this translation was not the best choice for tonight’s reading.

My brother had visited me just yesterday. It was my birthday. I had wanted to forget about it. During a war, you age several years every month. But he hadn’t forgotten. He stood at the door holding an enormous package. What’s in that box? We opened it together. I didn’t quite understand what it was. My brother had a taste for magic tricks. So here was a ladder, but not just any ordinary ladder. When you twisted one of its rungs, it turned into an ironing board.

I had been bothering my brother two years to put up a light in the basement. For the time being, he hung an extension cord through the window and, if necessary, one could… But, hell, there was a war on—wouldn’t it be safer to bring the cable around through the front of the building? He burst out laughing. Indeed, it would be safer if, during a war, there weren’t any loose cables about. Then I laughed too. There was so much danger everywhere, and I was worrying about an extension cord. At the beginning of the war, I had called my brother and asked what we were supposed to do with the windows when the air raid siren sounded. I had been out of the country when they explained on TV what to do in case something happened.

“Should I leave the windows open all the way?”

“You can leave them like that. Yes, that’s the recommendation” What will we do in the winter, I thought, but then quickly consoled myself with fact that the winter was still far off.

“And the curtains?”

“Don’t worry about the curtains. Leave them as you found them and get down to the basement.”

I found comfort in his composure. Yesterday he finally fixed that basement light. The cord no longer hung about. A simple click and the whole basement was illuminated.

Now I have a light. But what about my brother? The price for yesterday’s repairs was too high. If I had been just a little less insistent…

What did the fortuneteller do in that Korean tale?

My brother called back. He was back from the store, the loaf of bread still under his arm. He put it down and listened to what I had to tell him.

He asked me to bring the draft card to his office the next day at eight o’clock. I read it to him again. I could picture just how the slanted wrinkles on his brow deepened while he listened.

We’ll say goodbye tomorrow at eight o’clock in his office. What is one supposed to say at a sendoff like that?

They say that the first night is the hardest.

I sat back down at my desk and stared at the photograph from the cabaret. One of the knights was bringing his hand up to the side of his half-melon helmet, saluting the viewer.

Who could I turn to at such a terrible time? My address book was overflowing with friends, but I would have to struggle through this night alone.

As I turned out the light, I could hear how the clock hungrily gnawed away at the seconds, one by one.

Mars, God of Croatia (1922), Miroslav Krleža wrote the following on the nature of power:

The captain never listened to anyone who said that power could be wielded dishonestly, immorally, or stupidly. That it could come in despicable, tyrannical, or barbarous forms. Quite the contrary! To him, power stirs up bright and cheerful feelings like those borne by simple-minded children staring at the naked blade of a sword shining in the sunlight. The child is enamored with the nickel-plated blade and thinks to him- self—why not use it to cut and slice while it’s still all sharp and silvery? The captain regards his power through these child’s eyes and uses his authority with joy and gusto, swinging it around like the child with his naked, sharp blade. When the captain yells “Company right! March!” he has no idea that his shouting is the fulfillment of a scheme hatched in the Middle Ages by some shadowy organization, the same organization that tries to sell its wares from Thessaloniki to Baghdad. Those sorts of conspiracy theories are printed in the opposition newspapers, the kind that no decent person reads. But the captain isn’t aware that he is in fact a cog in the black machine, an unthinking, primitive, gigantic machine. Many years of training have dulled his half-intelligent, sluggish mind and ravaged his desolate, uncultivated soul. Those long years of training spring from the captain’s mouth with an amplified shriek, spouting programmatic nonsense.

On the use of Catholic symbols on Croatian military uniforms:

Christ does not hang upon the breast of the patriotic soldier like the symbol of an idea. Christ has become a barbarian fetish that soldiers condemned to death pin onto their filthy shirtfronts to protect themselves against the ring squad or the hangman’s noose. Even in the Malay Archipelago, men paint themselves blood-red and take statues of their gods into the battlefield as protection against impending death. Apart from his oleographed Christ, each soldier tucks a picture of Mary Mother of God of Bistrica inside the rim of his cap, or carries the image of Saint Roch in his pocket. In Croatia, there is more than The One True God. There are many, an endless number of Croatian gods… Practically the entire detachment has been dedicated to innumerable saints, beatified holy men, and guardian angels. And many of those condemned soldiers, who naively went off to rob, burn, slaughter, and murder, will crawl back on their bare knees to the sacrificial altar and lick the church marble, convinced that their necks had been saved, if they returned alive at all, by the luminous blessings of the Almighty. Back at the base, a huge Croatian flag hangs in the window in three rain-soaked colors, with a large head of Christ crudely and frighteningly added in paint. Faded and drenched, Christ’s face is distorted into a demonic grin, almost like the melancholy Pantokrator of Byzantine frescoes.

____________________________________________________________________

SPOMENKA ŠTIMEC (b. 1949) is a leading figure in the small but vibrant world of Esperanto literature. Active in Esperanto culture since her youth, she has authored dozens of works in Esperanto and Croatian, including novels, short stories, travelogues, plays, and textbooks, and has taught Esperanto language and culture in many countries. Her work has been translated into a number of languages, including French, German, Icelandic, Swedish, Chinese, and Japanese. A recipient of the prestigious Franz Alois Meiners Prize (FAME-premio, 1994), she has been a Member of the Academy of Esperanto and Secretary of the Esperanto Writers’ Association. She lives in Croatia.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

SEBASTIAN SCHULMAN is a PhD candidate in Jewish history at Indiana University, Bloomington, and the former director of translation initiatives at the Yiddish Book Center, Amherst, MA. His writing and translations have in appeared in The Dirty Goat, PaknTreger, Forward, and elsewhere. He serves as translation editor for In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies.