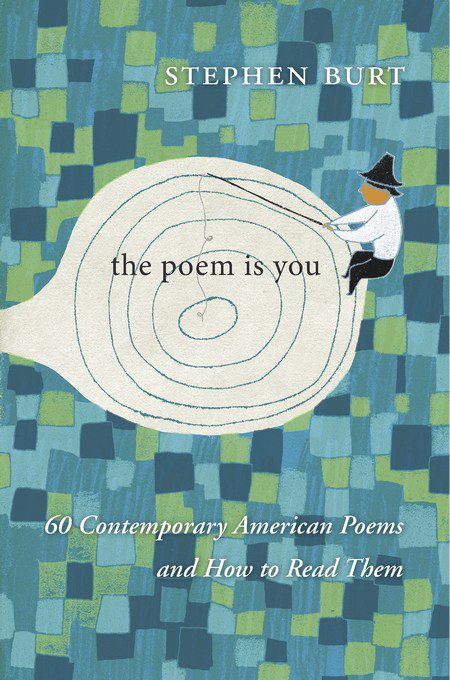

The Poem Is You: 60 Contemporary American Poems and How to Read Them

By Stephen Burt

Harvard University Press

2016, 432 pp

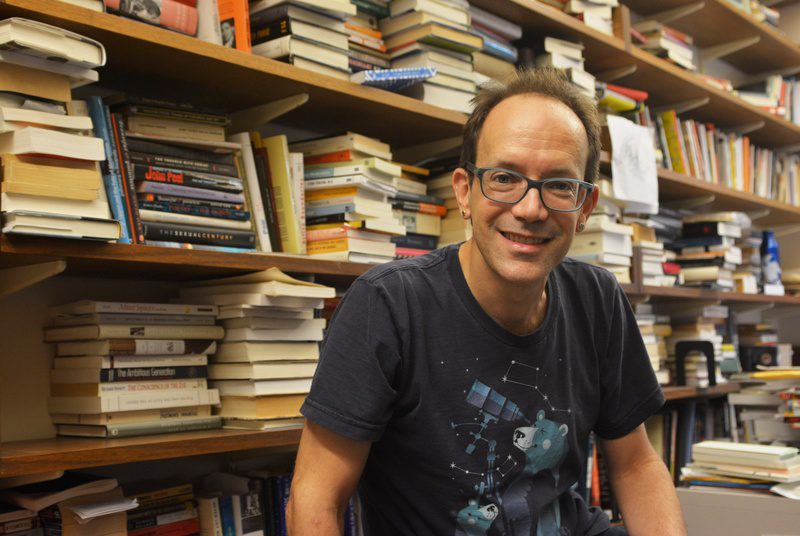

Stephen Burt’s new book is an intriguing hybrid – anthology, introduction, and critical study all at once. They choose one poem for each year since 1980 and append an essay of four to five pages. These essays, however, are not only about the particular poems, but also cover the poets’ careers, and explain where they fit into the poetry of the United States during this period. Though I have one reservation (more on this below), it is hard to conceive of a better vade mecum to the multitudinous panorama of that nation’s poetry in the last few decades. The clarity and accuracy of Burt’s writing, combined with their allergy to cliché, afford surprises on page after page. Burt reads more widely and more generously through American poetry’s various ecosystems, while still insisting on the importance of aesthetic criteria when we read and talk about poems.

One of the delights of the book is the way that Burt, when providing social context for a poem or poet, is never satisfied with a gesture toward presumptions they might share with the reader. Instead, they draw on the most recent research, quoting from history, social studies, and psychology among other disciplines, with a light touch but also with granular attention to extra-poetical matters. Because of its association with both I. A. Richards and Helen Vendler, Harvard University, where Burt teaches, has traditionally been a stronghold of an approach to poetry that scants social context. Vendler especially has argued for the importance of asserting poems as, first and foremost, aesthetic objects, rather than episodes in the critical narratives of cultural studies. Burt shows us that the critic can spend a good deal of time on, say, studies of teens’ online behavior, without ever taking their eye off the poem.

Burt has appeared on TED as an advocate of poetry, adroitly moving from autobiography to complex critical issues, as the TED genre demands; neither does Burt play safe and talk only about accessible poems, but spends a good deal of time on difficult work. Alert to a public acoustic unlike many other critics and poets, in this book Burt thoughtfully considers the deeper connections between the poems and the public reputations of some poets. For instance, they do not say merely that Adrienne Rich had many readers beyond the small group of poetry lovers, but they figure the social connections that may have enabled this, briefly suggesting the way that poetry can move in unreported patterns through our lives. Such a matter isn’t extraneous to the poems themselves, but is intimately connected with their pitch and range.

Some of the choices of poems are noteworthy. Including a Jorie Graham poem from 2007/2008 implicitly argues that she remains an important poet after the high point of her fame in the 1990s. I also wondered if the exigencies of their chronological structure forced Burt to choose weaker poems by Richard Wilbur and Kay Ryan. Burt has been one of Laura Kasischke’s staunchest advocates (she was interviewed in a New York Times profile of Burt that reasonably referred to them as a kingmaker in the world of poetry), and they interpret her work here so well that the poem, “Miss Weariness,” is possibly exhausted by it. Critics, no matter how generous and sophisticated, will sometimes think a poem is good, when the poet and themselves simply share a sensibility. Burt is a fine critic because this happens so seldom.

They write in places with magnificent PC verve. The criticism of sexism or ableism is frequently made for an audience that is converted, or at least is one or two brow-beatings away from conversion. It often overestimates shared presumptions, and thus is not always as thorough in its argumentation as it might be. In contrast, here is Burt discussing Brenda Shaughnessy’s poem “Hide-and-Seek with God,” which addresses her child who was born with severe physical handicaps:

It seems absurd, even insulting, to approach a poem with this topic and this affect by using the ordinary analytic tools of literary criticism: would it be better to love it, share it, cry, and then leave it alone? For some readers it might. And yet not to examine a poem so raw, so memorable, a poem about motherhood and loyalty and the messy emotions around life with any newborn, a poem that also addresses severe disability – not to use, with such a poem, the same lenses and gauges that we use with poems about hockey, or about falling leaves – would be to collude with the sexist, ableist social conventions that have made childbirth, motherhood, disability, and negative emotions around them unspeakable, unseemly, invisible. It is better to write poems about them, if they are your subjects, and better for critics to make available, when the poems work, hypotheses about how and why they work.

This is worth quoting at length to illustrate the tactful, yet forceful, way that Burt insists on the protocols of the critical profession in the face of social pressure. In other contexts, that pressure can grade from social to political, and while Burt understands the motivations, they do not believe the world is improved by pretending bad poems are good. They will spend the time and the effort to find the good ones that support the good cause.

Their catholicity notwithstanding, Burt has been especially engaged by the neo-baroque line in US poetry, or what they call “nearly baroque,” which they describe as poems that put “excess, invention, and ornament first.” In this book we find poems in this line by Angie Estes, Robyn Schiff, and Lucie Brock-Broido (the essay on the last is one of the finest in the book, a model of impassioned critical advocacy). Burt expertly lays bare the assumptions that would dismiss this kind of work as frivolous, emphasizing the strong sinews underneath its lavish textures. Here they are defending one of these poems, which includes in its phantasmagorical imagery dwarves “long / in their shadows and promiscuous:”

Brock-Broido appropriates – one might say with a vengeance – the slur that poetry, or her kind of poetry, is good only for teenage girls and old ladies: such people are just as important as the kinds of people (able-bodied adult men) who do not appear. Dwarves are important too, and they can have sex – they are “promiscuous,” which also means that they don’t hide.

Initially, this may seem funny because Burt is so serious. But then the passage turns back on those “able-bodied adult men” who consider people who have a different shape or different inclinations from them as “funny,” or, in the context of poetry, not worthy of serious verse. Burt is waiting up ahead for readers to realize how they can, unbeknownst to themselves, approach a poem ideologically from a position of social power or prestige; they also show here how poetry that seemed at first so eccentric in its means was never far from substantive issues.

At one point they remark that “‘American Poetry,’ now as in 1980 and 1960 and 1920, makes sense as a durable category for teachers and students and for readers and writers, since most American poets are closely related, in their influences and in the language they use, to other American poets.” Burt goes on to refer to poets whose styles were forged elsewhere and then spent significant amounts of their careers in the US, which makes them ineligible for inclusion here. But perhaps the point is not as straightforward as it might first seem. For starters, the three editors of New Poets of England and America (1957) went at their work with a different approach. Once one chooses the framework of the nation, then certainly such relations as these are immediately highlighted. But this does not always serve the art of poetry well. Most frequently it leads critics and anthologists to favour those poems that thematize the nation, or, in the case of poetry from the United States, which can be folded into the Emersonian story of individualism.

Burt is guilty of none of these kind of excesses, but it does seem strange to omit Paul Muldoon and Derek Walcott (two of the poets he mentions whose styles were forged elsewhere) from a book like this. Certainly, these two poets do not suffer from lack of attention (as Burt rightly remarks), but perhaps Ciaran Berry does, an outstanding Irish poet resident in the US for many years now, whose work is close to the neo-baroque style that Burt advocates. Berry helps us understand the limitations of Burt’s nationalism (however generous its dimensions): his poems find no real context in Ireland at the moment – there is no one like him, he doesn’t write about ostensibly Irish issues – but as a poet who has learned much from the legacy of Marianne Moore, he sits comfortably in the presence of Brock-Broido, Estes, and Schiff. A nationalist approach directs attention away from him, and perhaps many others. More generally, I’ll wager that if we lay aside the national story for a generation or two, we’ll find more interesting things to say about poets as various as Elizabeth Bishop, Wallace Stevens, W. H. Auden, Thom Gunn, and Claudia Rankine, to name but a few.

Burt might respond that all frameworks impose limitations, and as I have suggested they apply the nationalist approach with great sensitivity, informed as much by what the United States is now, as by what it hopefully might become. In the introduction, they suggest that a sequel may follow, covering poetry from outside the United States. While I think that, at this stage, there’s little to be gained in dividing anglophone poetry into the United States and The Rest of the World, I can imagine no better critic to tell me about what’s going on anywhere that a poem in English is being written.

— Justin Quinn

_______________________________________________________________________

JUSTIN QUINN’s Between Two Fires: Transnationalism and Cold War Poetry was published in 2015. He is Associate Professor at the University of West Bohemia.