MONSIEUR DE BOUGRELON

(an excerpt)

Monsieur de Bougrelon

A novel by Jean Lorrain

Translated from the French by Eva Richter

Published by Spurl Editions

CHAPTER ONE

CAFÉ MANCHESTER

Amsterdam, it is always water and houses painted black and white, all windows, with sculpted gables and lace curtains; the black, the white splinter in the water. And so it is always water, dead water, iridescent water and gray water, alleys of water that do not end, canals guarded by dwellings like enormous dominos; it could be gloomy, and yet it is not sad, but eventually it is a bit monotonous, especially when the water freezes and the gelid pewter of the canals no longer reflects the small, pretty dollhouses, upside down with front steps high in the air.

There was a strong wind on the Amstel that day, a wind to sweep away the sweepers themselves. At the Dam, there was the spectacle (which we had already seen too many times) of the tram station and the crowds around it; of fur caps pulled down over violet ears, cabmen and drivers blossoming with rosacea, necks disappearing behind mufflers, and those strange little old men who, with eternal drops of frost on the ends of their red noses, hawk omnibus connections at the highest prices. But everyone needs to live, and the surprise of hearing dangüe for merci, and the surprise of gathering freezing snot from the back of their gloved hands is one of the pleasures of tourism in Amsterdam.

Oh, these people of the North! The Dutch man, by the way, is rather ugly, and the Dutch woman resembles him. Those old women in black velvet hats perched upon caps of lace, embellished at the temple with hemstitched medallions of gold, apparently work better in the old master paintings than they do in the streets. And the Zeedijk (the Rietdijk of Amsterdam) does not come to life until nighttime. As for the Nes – where good, shapely, strapping men, very blond and very pink, innocently approach you from dive bar entrances, their plump bodies bulging out of their long hotel porters’ cloaks and their faces radiant – it had lost its mystery for us: we had already visited it too many times as well. This is surely human ingratitude, because the Nes had so delighted us the first night!

We used to love those heavy doors that opened abruptly to reveal, behind a row of tables, a heap of flesh and spangles, raised like a dessert on a faraway, luminous platform. “Dames françaises! Come in, Messieurs, we speak French,” and this from the decent, chubby-cheeked giants, who bowed and smiled with full lips, but they were good, honest smiles, unknown in Paris; they did not release for a minute the doorkeeper’s ropes they held in their hands. Indeed, at every entrance on Nesstraat there was the same sudden appearance of nudity and dazzling fabrics, the same patriotic offer, dames françaises, and the same salute.

Oh, only French women on every Nes, from the Belgian fogs to the distant parts of Holland, they are in every region!

Oh! How we are happy to be French

When we travel to foreign lands.

Amsterdam’s red-light districts are relaxing and refresh the soul; there is a sense of geniality there that is unknown in the Latin countries, and these devilish exhibitors, these solid doorkeepers to hell, defuse malice with their good shiny faces and their good thick hands in fur gloves, looking like thoroughly honest major-domos under their gold-tasseled caps. But apparently we had seen too much of them.

Nes, Zeedijk, the Dam, and even the museum did not speak to us anymore; there are days like that in life. We wandered through the city like flotsam, along the frozen canals, hurrying around street corners, for the great wind, as I have already said, blew forcefully that day on the Amstel.

It was bone-chilling outside, savagely cold, and the many Schiedammers we had knocked back in every cellar on Kalverstraat had hardly perked us up – there are days like that in life too – and so we meandered under January’s north wind, pitiable and glum, when an odd sign captivated us: Café Manchester.

It was in one of those uniform black-and-white Amsterdam streets: a small old two-story dwelling, very low beneath an enormous roof that crowned it from its gable nearly to the first floor. The lodging seemed packed in on itself, as though squeezed underground, and we had to descend five steps to find the front door and the only window, hung with wide net curtains of taut guipure, which opened just above the ground; on the other levels there were small irregular dormer windows with closed shutters. Café Manchester! It had the look of a lantern. It even had a pulley at the top of its roof to raise supplies and furniture. What did they sell in this café? In this Café Manchester, where apparently they spoke French as well as English.

The cold was intense, the house dubious; we went inside.

“Take your seats, Messieurs, sit! The women are coming. Déborah, hey! Gudule, French gentlemen are here.”

An old venerable woman spoke (a wide black velvet bonnet rested upon her lace cap), an old woman in a shawl, in bracelets and cameos, and Déborah entered the little low room with minuet steps, a great toothy smile, and, with knees bent, three curtseys. The girls are far less polite in France – and what style! What modesty, and what distinction! . . . We took our seats. Oh, what a cozy interior! The table was polished and shiny, the furniture waxed until it reflected, and the washed walls gleamed like moiré silk, with reflections cast throughout and a good earthenware stove in the back . . . There was even a rack made of island wood, a pipe rack, with pipes that Jan Peters and Cornelis surely once smoked at night; it was charming, but the girls were less so.

Low . . . waisted and short-legged, as blond as a towline, with an absentminded profile and a flushed complexion, Déborah was overfamiliar, even eager.

With a playful temper, she could have pleased at the age of eighteen, but Café Manchester had evidently fattened her and given her wrinkles, and the poor good girl, as red as roast beef and as curly-haired as a sheep, deplorably insisted on climbing onto our knees and dipping into our glasses.

Her cheeks, scrubbed with sand like copper pitchers, were blindingly radiant.

Déborah was nice and rinsed thoroughly, much like the interior of a Dutch house, but her hair was thinning, the blue of her eyes was bland, and her soft skin exuded a heady musky scent. As it happened, though, she had an affectionate, even caressing, nature, with hands that were easily led astray, and she was touchingly obstinate in repeating to you, “Be gentle, Monsieur, don’t fight it!”

Gudule tempted even less. Called out by the house patronne the moment she tried to soap up the floor of one of the upper rooms, this pretty servant girl (a real workhorse) rushed down the stairs in the makeshift outfit of a proper worker – a linen shift thrown over an underskirt, her feet naked in clogs.

“To serve you, Monsieur!” She dove into a brusque curtsy. “Beer is on you, right?”

And Gudule made herself at home.

If Déborah stank of musk, Gudule had a strong smell of hot water and potash, but her breasts were firm and the skin of her arms was as granular and prickly as a turkey’s; her washerwoman’s arms could have pleased only cart drivers. Beneath her sleeves, boldly rolled up, she was a mean peasant woman, interested neither in her pitcher of beer nor in men’s kisses, a real Teniers, with a square figure and hard limbs; her face, though, was rather ugly, and her smile had a few holes – the humidity of the Netherlands is so catastrophic to delicate dentition!

Déborah had lighted a lamp. The woman in the black hat, seated at a distance, had put on a pair of enormous spectacles and was keeping herself busy, her nose in her knitting, maneuvering long thin needles. From time to time she ventured a quick, discreet look at us, a debonair smile, a mute “go on, my children, don’t be ashamed” that reassured and soothed, like a blanket of cotton creating tranquility and security. We had already bought Déborah five Schiedammers and Gudule four bottles of beer. Oh, the peaceful and homely Dutch interior!

It was at that moment that He appeared.

He, Him, the epic silhouette of this misty country, of this city of dreams, the prestigious hero of this tale.

____________________________________________________________________

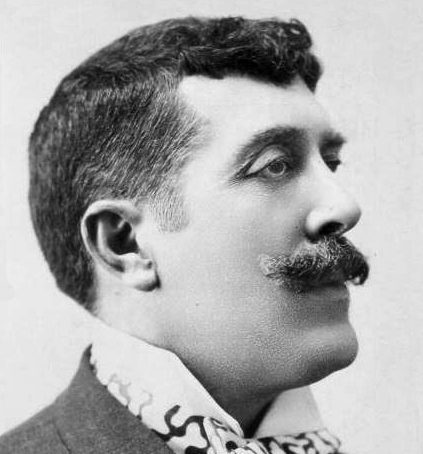

JEAN LORRAIN, born Paul Alexandre Martin Duval, was a novelist, critic, and dramatist, and one of the most conspicuously Decadent figures of fin-de-siècle France. Masks and disguises are recurring themes in his work, as is Parisian low life, satanism, ether, homosexuality, and the aristocracy. In 1897, he wrote Monsieur de Bougrelon, and shortly after, Lorrain left Paris to live in Nice. His stay at the Riviera began an intense period of creativity. In 1901, he wrote his best-known work, Monsieur de Phocas, which he followed a year later with his fantastical aristocrat saga, Le Vice errant. His health declined due to syphilis and his abuse of drugs, and he died on June 30, 1906, of peritonitis, at the age of fifty-one. It was rumored that when Lorrain’s grave was opened in 1986, the body of “Sodom’s ambassador to Paris,” as biographer Philippe Jullian called him, still smelled of ether.

Monsieur de Bougrelon is being published Nov 1, 2016 by Spurl Editions

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

EVA RICHTER translated My Suicide by Swiss author Henri Roorda, published by Spurl Editions. Her writing has been featured in Columbia University’s Catch & Release, and as an editor for the translation journal Asymptote, she edited Marcel Schwob’s Mimes (1901) in English translation.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more about Jean Lorrain:

A review of the novel at The Complete Review