THE TALE OF AYPI

(an excerpt)

II.

According to legend, some 300 years ago a group of strange men from unknown lands came ashore on this beach. The unexpected guests had dropped anchor, not encountering any sort of welcome until a young woman, Aypi, who often gathered beautiful stones from the beach, came across the newcomers by chance. Not being particularly timid, she spoke with them, and it seems they were inquisitive folk, since their talk went on for some time. When they did at last part, the strangers gave the woman a stunning ruby necklace. The thing shone with such an arresting sanguine glow that Aypi was tempted to immediately put it on, and as soon as she re-entered the village, everyone took note of the remarkable trinket.

Indeed, the necklace from across the seas dazzled all who crossed her path. She strutted haughtily through the winding streets of ramshackle stilt-propped huts, until there wasn’t a woman or girl left in the village who didn’t envy her.

As she passed by one young wife’s door, the woman grabbed her arm. “Come on Aypi, tell me,” she asked suspiciously, “where’d you get that fine piece?”

“‘Where’d you get it?'” smirked Aypi. “That’s what they say to a thief, girl! Some foreigners I saw down on the beach gave this to me.”

The other woman narrowed her eyes and asked insinuatingly: “They got enticed by your looks, did they?” spearing a meaningful look at the crowd of women gathered around.

“Oh no, girl,” cooed Aypi, who had always been proud of her beauty. “It’s not that at all, don’t be silly.”

“Strange… so why’d they give you that, huh? ‘Cuz a your Persian-like name?” she quipped, as the circle of women grew ever tighter around them.

“Speak up quick, girl, why’d they give ya that? Stop wasting our time, and spill the beans!”

Aypi gave them a sugary smile. “I told them about our life, our village and our chiefs, and when I showed ’em how our men catch fish, they laughed and laughed.”

Now the women gaped even more.

“They gave you such a thing for that nonsense? Any of us could have told them the same, if they’d only asked!”

“I told them about the coast here, and listed all the villages. Not one of you know better’n me how many people are in each village!”

This made their stomachs knot: Look at that smug tramp, and see what luck she’d had! All the men’s eyes were on her, as it was, and now she had that ruby necklace!

Only one sighing wreck of a crone remained aloof from the crowd, puckering her leathery face.

She wiggled her chin, pursed her lips, then, muttering and grumbling, she made her way towards Aypi, even pushing aside some of the onlookers. “Stand back, it’s none of your business!” the young women scolded her, bewitched by the ruby. The grandmother was forced to wait until things calmed down, and her toothless but carefully weighed-out words would be heard by all.

“May yer eyes cloud over, hrmph,” said the crone, waving her petrified clot of a fist. “You’ll bring calamity down on us all! Draw a disaster! ‘Round your neck the outsiders didn’t hang that cursed necklace for nothing, no, they wouldn’t have! May your nipples crack, yes crack! You come back here and you’ve betrayed all we’ve got, you mug of mugs, hmmph… you told everything, there’ll be no plenty on these shores no more, you’ve snowed a blizzard on our happiness, a blizzard!”

The old woman wandered off, muttering, “Would that yer eyes cloud over, ye bitch! Likely you’ve gotten us all murdered, yes, murdered!”

She was of the same age as the Flood and had seen everything there was to see, so fear began creeping into the listeners’ hearts as they heard her curses. The women immediately dispersed, and left Aypi standing dumbfounded and alone in the middle of the street. The words from the crone’s mouth, “She’s snowed a blizzard on our happiness, a blizzard!” echoed in their ears as they fled.

In the evening the town’s whitebeards held a meeting. As he was leaving their council, Dadeli, the village’s best man and Aypi’s husband, dragged like an anchor the weight of the sentence dealt out to his darling wife. The elders’ words rang in his ears: “What she said to the strangers doesn’t concern us. What scares us is that she had dealings with them at all. She has no place among us.”

After the door had shut behind Dadeli, one of the old councilmen abruptly spoke out what had been in everyone’s hearts without even knowing it:

“Well let’s hope it’s for the best!” he lamented. “She tortured everybody with her beauty. Enough! Out of sight, out of mind!”

The next day, before the town had begun to stir, on the pretence of showing her a certain islet, her husband sailed out to sea with her.

“Wear your best clothes,” he had said, “and put on that ruby necklace too, look how it suits you!”

They had left the village before sunrise. As they got on the boat, Aypi could already sense the tension, but only after they had arrived and climbed up the lonely peak did she take a look into her husband’s frozen eyes and knew her fate. In the final moments, she broke away from him in an attempt to flee, but Dadeli’s burly arms encircled her. From the cliff’s very pinnacle he pushed her down into the frothing swell. The strange necklace’s weight gave her no chance to swim, but dragged her down, twisting, into the depths of the briny waters.

Ever since, the people on the coast were haunted by the fear that those uninvited guests would return someday, bearing not gifts, but weapons.

III.

Sometime in the early afternoon, a group of local men gathered on the beach beside an old scuttled sailboat that had been there since their grandfathers’ time. They would roll their cigarettes and endlessly puff on bitter tobacco, their faces wrinkled by old sorrows.

The impending irreparable calamity of recent years was now upon them: they’d been ordered to immediately relocate to the city post, where new homes made of concrete awaited them. Some of them had already moved and began acclimatizing to the new location and lifestyle. Those who remained, still lived with a glimmer of hope, however slim, that perhaps this time, like several years before, the powers above would relent. For that reason, the stragglers hemmed and hawed and seemed in no rush.

Actually, the whole affair had begun with pleasant and even joyful news. Several years ago, a group of medical scientists conducting an investigation in the area had declared, “The whole coast is simply a natural wonder!” As they further explained, “the continuous abrasive force of the waves against the coastal shelf creates elevated levels of ionization in the atmosphere. In such conditions, people suffering from illnesses whose cases have been deemed hopeless could make full recoveries. If, for example, you were to open a sanatorium for asthmatics and people with other respiratory diseases, this stretch of coast would be simply invaluable!”

Following this, a stream of renowned and reputable administrators poured in from the capital to the secluded village, where previously, for months and even years at a time, no stranger would set foot. The scientists brought along with them every kind of instrument, conducted in-depth examinations of local conditions, debated incessantly, and concocted a number of schemes.

As the village fishermen observed all this commotion, at first their heads swelled with pride. Look here, if they hadn’t been living for generations in such a health-giving, astounding location!

In no time at all, the strangers began to transport construction materials to the site. A line of monstrous vehicles rolled in bearing a number of wheeled wooden houses, in which it was confirmed the construction workers would reside. The village children immediately gathered around them, knocking and poking the trailers to test the vehicles’ strength against their own, and marvelled at the smell of new paint as they sniffed in the scents of the trailers. A few of the smallest toddlers had even licked the wheeled houses out of curiosity. The older boys soon clambered up onto the roofs of the trailers and spent hours there gazing at the sea, arguing about nothing at all and dreaming until dark, as boys always will. As they understood it, this coast would quickly become a fine place and things would pick up considerably. If hunger and darkness hadn’t chased them off the rooftops of these dwellings, they would be ready to stay night and day up there, speculating about such matters.

The joy of both boys and men was short-lived. At first they had congratulated themselves, “If they build this sanatorium here, then they’ll build us nice new brick houses.” Soon though a disturbing thought arose – “If they build it, what will become of our village?” This negative aspect only then became clear, and soon the matter was resolved decisively and contrary to the hopes of the fishermen: The village had no future, fishing was now forbidden, and never mind all those who had always done this, let them find new jobs in the city. The fishermen’s elation had been extinguished with a single breath only to be replaced with grief and panic: What should they do? Whitherto should they run? Whom should they entreat, and from what quarter could they expect help?

Then, without warning, construction ceased of its own accord, and the fishermen found themselves free for a year. The trailers vanished. Due to poor planning, funds had apparently run out. Several months later however, the process began all over again. As it turned out, this time everything was much more serious: an order came that everyone must be deported from the area, without causing any interruption to the ongoing work.

Half a century ago these old fishermen had rowed all the way to the Russian capital just to make a name for themselves. Then the times had changed, and, like broken toys, the men now sat down in the shadows of this rotten ancient sailboat just beside those same wasted dinghies. At first no one made a sound because unsurprisingly they’d already discussed all their options. It was clear enough. Without any new suggestions to be made, what could they possibly discuss? No one wanted to start anything, so they sat, each minding his own business. Finally, Nur Tagan, an elder fisherman, stepped forward and launched into a tirade expressing his long-held opinions:

“Yes, indeed, men, my guess is as good as any, and I say from now on we won’t be able to change a thing. There are things we can do, and things we can’t. We’ll be moving soon, and our ancestors’ lands will slip through our fingers, but what can we do? Tomorrow I might go to the city and see my new house there for myself. If you want to come along with me, hop onto the mail truck.” After a few moments of reflection, he added “Don’t look so sad. Honestly, most of our children have already been there for a while, let’s not be stubborn.

After that, a bad-tempered discussion sprang into life. No one seemed to get much consolation from Nur Tagan’s opinion, though his fellow long-beard Mered Badaly did take his side because of his two boys, both of whom had already been living in the city. They had studied or whatnot there, taken up city work, and eventually dropped anchor. The elder, Kerim, was married, and the younger, Kerem, had no desire to return to the village.

“Hrrm! Ahem!” coughed Mered Badaly, clearing his throat as a preface to his speech: “You’ve got it right, long-beard. We ought to live near our children. I stayed up all night thinking about it, and spent all the evening pondering it too. How couldn’t I? Come on; speak up, which of you hasn’t been bashing your head against the wall over this? I have just one thought: without us, in the city I mean, won’t our grandchildren become complete strangers in no time at all? Already we can’t understand our own children when they talk, so you can imagine for yourself how it will be with the grandkids. They’ll be lost, there’s no denying it.”

“Now, there’s a reason I say this, men. I make conclusions based on what’s in front of me. Much as they boast, if we’re not around, their affairs won’t be so respectable, is what I say. You can see something particularly sheepish written across their faces. Last time the boys visited, the old lady and I couldn’t believe their behaviour. We didn’t understand why they sulked so, good heavens if they had even said a word to us! Yes sir, I asked myself if they hadn’t forgotten how to talk! It’s like they didn’t come from the city but the deepest desert. They brood without setting their eyes on the people ’round them, and don’t utter a single word. Yes indeed, if you’ve got nothing better to do, come see it for yourselves!”

My older boy Kerim, when I asked him “Son, why don’t you ever say a word from morning to night, like your mouth’s full of water?” he said “Father, We’re focused on our inner lives.” How am I to understand this “inner life” of theirs? So I told him, “Listen boy, perhaps it’s fun for you to live inside yourself, and you don’t need anyone else to talk to, but we sure do. If you clam up, who will us, old folks, talk to? Who can we discuss things with? If you won’t talk with us, and then someday if your children – our grandchildren – won’t talk to you, what’ll be the end of all this?” And so he answers “Everyone must act according to their ‘Tellekt.”

Tall Hodja, confused, raised himself a little:

“What did you say, old man?”

“T-E-L-L-E-K-T” said Mered Badaly, spelling it out especially for him. “That’s what he said, how am I supposed to know what he means?”

A younger fisherman in a straw hat couldn’t stop himself from chuckling as he corrected his elder – “It wasn’t ‘Intellect’ by any chance, was it, uncle Mered Badaly?”

“Ah yes, so it was, he said something or other like that, may well be so. Will you look at the words these people come up with! If you try to repeat it your tongue’ll break. Really, when they speak in this way, it’s no easy thing for the likes of us to understand. How about that, those words coming from their mouths! Anyway, is that a sign of intelligence? These folks, I don’t reckon they’re all that intelligent; in fact it’s probably all a result of soft-headedness.“

“Basically, I’m saying that all of these things result from them not being around us, what else could it be? It’s clear they’re having a fine time of it in the city without us! We old folks are obviously needed there. And how much! Otherwise the traditions of our ancestors will slip away into the sands, and our children will lose their native language. How else can they be brought up with education and learning, and, as it were, humanity? Look here, we let them fly too early from the nest, or we wouldn’t now be facing this kind of trouble. We weren’t able to teach them one third of what we’d learnt from our old folks, that blame’s on us. Television and books might not be teaching them anything bad, but they can’t get the example they were meant to take from us, from those other things, and that’s a fact. Sooner or later we’ve got to do the hard work ourselves, because no one else can.”

“I couldn’t have said it better myself!” responded Hodja, standing up. “I’ve seen this television thing of theirs! Isn’t it a wonder! A spectacle, alright! Whatever you want to see, there it is: on a summer’s day you can see snow – if it pleases ye! And in the winter you can see scorching heat, it has that too. Finer than you can imagine! Although you can’t touch anything with your hand, there’s great crowds inside it: jumping, dancing and even walking on their heads. One sings, one plays an instrument, one swallows fire and another kills you with laughter – whatever you like! I wouldn’t say it’s just interesting; it’s impossible to stop watching. If you kneel down before it, so long as those dancers keep dancing, you’ll sit there heedless of all your cares and duties.”

“But whatever you might say, I never saw this place on that television. I came back from the city without learning we existed at all. If you think that’s nothing, well, the people who watch television also listen to it and most of the ones who speak on it are young people themselves. As long as I have watched it, I’ve never seen seasoned wise old folks giving advice to youngsters and I certainly didn’t see any well-behaved child pouring water from a pitcher onto his grandfather’s hands. Why is this? I thought to myself, is this a case of “Yesterday’s sparrow teaching today’s sparrow how to tweet?” It’s a matter of training them, see? So if you can go after them, then go, by all means! But we don’t benefit them at all if we just keep sitting on this lifeless coast here, doing nothing.”

“That’s what I’m saying too,” agreed Mered Badaly. “Moving to the city quickly is the best thing we can do; let’s be near our grandchildren, perhaps it will do them some good. They can’t develop without us and what’s more, without us they won’t know themselves – no knowledge at all of their elders. What can you expect from children who grow up in such a way? They’ll probably make all kinds of mistakes we can’t even imagine, because big and small they’re always in front of that television. They take their lessons from it and that’s why their behaviour is going way off. Let’s say that box shows some house burning in the far corner of the earth – they’ll gasp in horror and pity the people burning inside, but they have no idea about their own neighbour lying sick in bed for however many months; they have nothing to do with him, though he’s living right there next to them!”

Gutly, the young fisherman, who had taken correspondence courses from the institute and went to the city every now and then, straightened his fur hat. “Walls of iron and concrete interfere even with radio waves and they’re a definite obstacle to emotional waves.”

“What? You want to make a joke of this?” Hodja grumbled. “You’ve forgotten that people are supposed to be compassionate towards each other, otherwise what’s the difference between us and animals? Wearing clothes? You can always put clothes on a horse or a dog for that matter!”

Mered Badaly continued, despite the interruptions, summarising briefly: “Well then, that’s what this ‘inner life’ of theirs means.”

Hodja had another question: “Old friend, we’ve heard of the ‘next life,’ and we’re living ‘this life’ right now, but really, what kind of life is their ‘inner life?’ Where is it actually? Wouldn’t it be a bit cramped?”

Gutly had the answer before Mered Badaly could respond. A pleasant smile appeared on his round face to show that, as usual, he had an especially choice remark: “Hodja, their “inner life” is located right between ‘this life’ and ‘the next life!'”

The men all laughed at the joke, and then they began to make fun of the village laughingstocks. “What’s more beautiful,” one asked at Pirim’s expense, “a bottle of vodka, or a woman? Which one is hotter, and which one is quieter?” For a while they forgot all about relocation. How can you escape worry though, especially if your worry is justified?

____________________________________________________________________

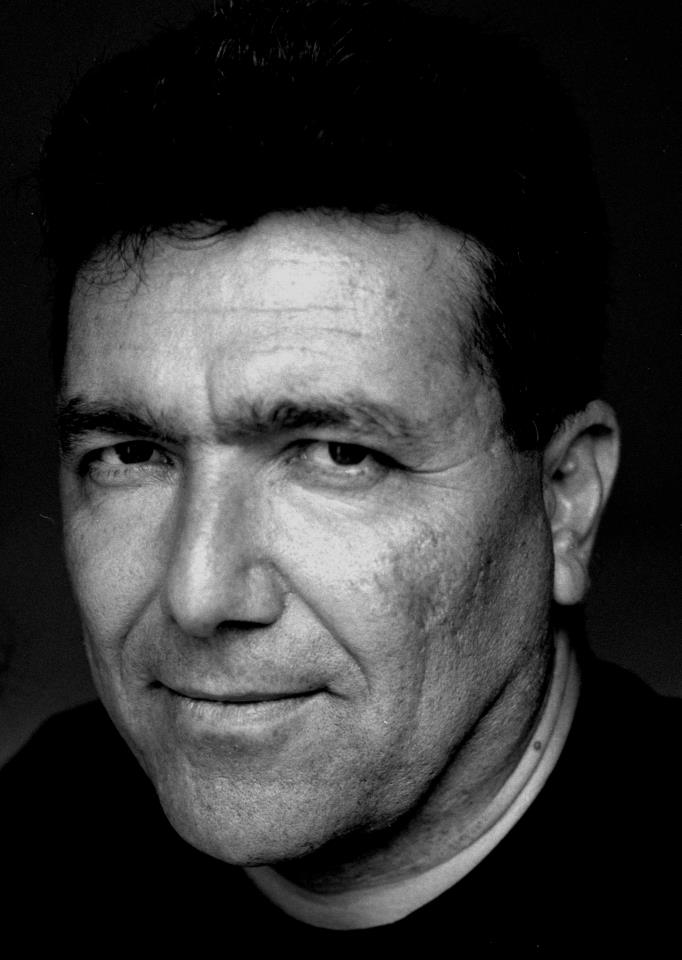

AK WELSAPAR was born in 1956 in the former Soviet Republic of Turkmenistan. In 1993, after spending a year under house arrest, he was excluded from the Writers’ Association following the publication of investigative articles about colossal ecological problems in Central Asia, mostly caused by the overuse of pesticides needed for cotton production. His work was banned and confiscated from bookstores and libraries. He and his family have lived in Sweden since 1994, where he is a member of the Swedish Writers’ Association. Ak Welsapar writes in Turkmen, Russian and Swedish.

Ak Welsapar has contributed articles to such journals and newspapers as Literaturnaya Gazeta, Druzhba Narodov, Soviet Culture, The Washington Post, and many others. He is the author of more than 20 books, including A Long Journey to Nearby (1988), This Darkness Is Brighter (1989), The Bent Sword Hanging on the Old Carpet (1990), The Tale of Aypi (1990), Mulli Tahir (1992), The Cobra (2003). He remains a proscribed writer in Turkmenistan and his name has topped the list of black-listed writers since 1993.

The Tale of Aypi is being published by Glagoslav Press on June 30, 2016

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

W.M. COULSON is a scholar of Turkic languages, who has also been involved in several other projects involving Turkmen letters. Residing in the Central United States, W.M. Coulson visits Turkmenistan only occasionally but always enjoys contact with a nation that has produced so many fascinating literary works.