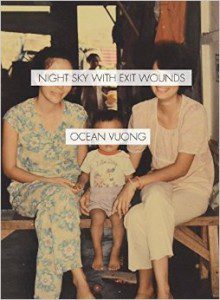

Night Sky with Exit Wounds

Night Sky with Exit Wounds

By Ocean Vuong

Copper Canyon Press

89 pages

Occasionally there is a book so exquisitely realized that a reviewer wants simply to point to it and say “read this.” Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds is such a book. Not because it is perfect, but because it is the record of a voice that should not be ignored.

And, if you are interested in American poetry, Vuong’s voice cannot be ignored. Considering the accolades he has recently won, including the Whiting Award, the Ruth Lilly/Sargent Rosenberg fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, praise from several generations of poets and interviews in major publications, this book, and he, are about as promoted as poetry gets.

These poems are elegantly devastating. The threatening beauty suggested by the title is not so much the theme of the collection as it is a primary tenet of Vuong’s poetic vision. What is threatening is thrilling, whether it is the void between silence and language, as in “Logophobia” and “Anaphora as Coping Mechanism,” which illustrate the physicality of language for Vuong and the way that words, like time, are forces with the power to change everything, though often they change nothing. In this world language ages and corrodes: “We had been sailing for months. Salt in our sentences.” But language also has the power to create and destroy. Here stars are “the exit wounds / of every / misfired word.” These poems delight in the power of language and its shapely, dangerous sensuality.

But physicality in this book is certainly not limited to language. Sex is ever-present here, but rather than consummation, sex in these poems is a failed attempt at leaving the loneliness of the body. The desire to lose oneself in another seems to lead inevitably to disappointment, a feeling that is not masked or made more lovely than it is. “Devotion” begins:

Instead, the year begins

with my knees

scraping hardwood,

another man leaving

into my throat.

There is guilt in these poems that is unassuaged even as it sublimates into language. “Because it’s Summer” describes a carnal rendezvous in a baseball field:

because you kissed your mother

on the cheek before coming

this far because the fly’s dark slit is enough

to speak through the zipper a thin scream

where you plant your mouth

to hear the sound of birds

Vuong emphasizes the unsettling juxtaposition of beauty and violence, sex and danger, mother and the man who “steps out of summer / & offers you another hour to live.” But there is nothing incongruous about these juxtapositions; instead a sense of acceptance — not resignation — infuses these poems, as desperate acts and feelings are made to sing.

The relationship between parent and child, but especially father and son, is probed in several poems here, including “Telemachus,” “My Father Writes from Prison,” “In Newport I Watch My Father Lay His Cheek to a Beached Dolphin’s Wet Back,” and “To My Father / To My Future Son.” Several poems use phrases and lines in Vietnamese, Vuong’s first language. The collection thus is deeply, at times even startlingly intimate, and yet the poems never feel claustrophobic. That is partly because Vuong artfully employs allusion to give these personal poems another level of meaning. Using Telemachus to talk about being a son, or a painting by Mark Rothko to turn 9/11 into art, or an epigraph from Jeffrey Dahmer to add uneasy drama to a lyric of failed love — these poems reach outward and inward at once, attuned to the needs of their maker as well as a larger cultural reality.

But mostly it is the poems’ language and lithe form that keeps us listening through our eyes. Couplets are common, but several poems use more intriguing and interactive forms, like “Seventh Circle of Earth,” which gives voice to Michael Humphrey and Clayton Capshaw, a gay couple murdered by immolation in Texas. The poem consists of seven footnotes across two blank pages, with the lines of the poem at the foot of the page. The poem ends:

6. mouth. / Each black petal / blasted / with what’s left / of our laughter. / Laughter ashed / to air / to honey to baby / darling, / look. Look how happy we are / to be no one / & still

7. American.

These are poems that inhabit their subject with sure, subtle language and primeval empathy. They would almost be too beautiful for their mostly dark subject matter if their beauty wasn’t so strange and haunting. The poem “Aubade with Burning City,” about the fall of Saigon, weaves snatches of “White Christmas,” which was broadcast on the radio as a signal to begin the city’s evacuation, with violence and surreal horror:

On the bed stand, a sprig of magnolia expands like a secret heard

for the first time.

The treetops glisten and children listen, the chief of police

facedown in a pool of Coca-Cola.

A palm-sized photo of his father soaking

beside his left ear.

These poems are light even at their darkest. The lines are feathery, floating over the page, rhythmically and musically engaging, while Vuong’s beguiling voice reaches deep into memory, experience, hope and loss.

In this heightened, sensuous voice, genius and sentimentality are only a hair’s-width apart, but the poems here mostly remain balanced between the two, only raising an arched eyebrow rarely, as in the line “here is my hand, filled with blood thin / as a widow’s tears.” Here the soft surrealism seems inorganic to the poem and calls more attention to itself than to the mood and spirit it seeks to convey. But this is an exception. Generally the narrative voice and imaginative imagery here are compelling.

Night Sky with Exit Wounds is a book of disquieting intensity. These poems don’t grapple with the universal uncertainties of the living and the dead so much as they lie with them and become one. This is language that has been indelibly lived.

–Stephan Delbos