The Selected Poetry of Emilio Villa

Translated by Dominic Siracusa

Contra Mundum Press

708 pages

Who are the greatest Italian poets? Ask the most turned-on and tuned-in anglophone literary heads you know and you’ll get a rich list indeed, including Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Montale, Pavese, Leopardi, de Palchi, Calvino and Merini. Mama Mia, some wise guy might even throw in Vinnie Barbarino, but he, like Dominique Wilkins, is more accurately “poetry in motion.”

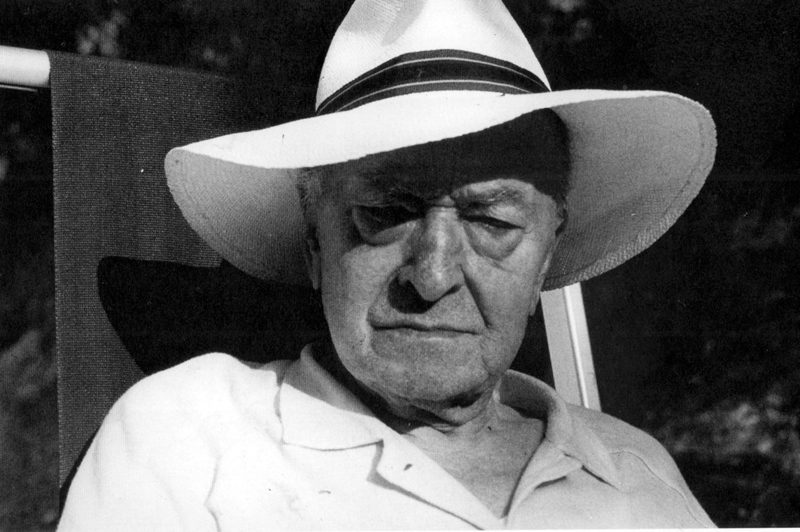

Does poet, scholar, translator, philologist and art critic Emilio Villa (1914-2003) deserve a spot on that roster? Dominic Siracusa, who has meticulously edited and helpfully annotated this volume in the face of the distinct challenges of Villa’s obscurity, his temporary exile from Italy in Central America, and his penchant for destroying his own work, would definitely argue in the affirmative.

Siracusa’s thesis, as presented in his introduction, is that placing Villa in the canon of 20th century Italian poetry radically disrupts the way we think about the Italian avant-garde. Without pretending to read Italian, this humble critic would concur. Because even when we place Villa’s work in the context of poetry as a human endeavor, it prefigures much of what would come to seem innovative about American poetry in the second half of the 20th century.

But that’s not really what’s interesting and finally rewarding about this book. Villa is zany: energizing and enervating by turns, emotionally and intellectually. His is a polyphonic voice. From high to low diction, Italian to English to Latin to Spanish to French to Sumerian to Akkadian, to drawings and photographs — sometimes all on the same page — Villa’s concept of “poetry” was all-encompassing.

But it didn’t necessarily start out that way. One thrill of this book is the wild contrast between Villa’s early work and his last. If, as Ilya Kaminsky suggests, great poetry begins in elegy and ends in praise, Villa’s body of work is great poetry in the sense that it begins in elegy and ends in praise of the malleable force of language. But such strictures are not necessarily relevant to a mind as iconoclastic as Villa’s. Here’s part of an early poem, “Medieval Town,” published in 1934:

A people of grim and holy thoughts,

Like old angels hanging from the sky,

Rolls across the bells’ waves.

Melancholy pervades Villa’s first book, Adolescence, but Villa’s work quickly thickens and grows stranger. Yes, but Slowly, published in 1941, is a departure from Villa’s earlier poetry and one that seems to cross the best of Ginsberg and Beckett. The collection is a turning point in the development of Villa’s style from the personal to something more experimental and expansive. Here’s part of the title poem:

we wait, patience will come, let’s get to the thing:

it will come when in the evening in the little town

where the incandescent clouds of dried meals cross off shore

and the shouts of barn dances or halls, in a winy

prose, when spring tenderly milling between false notes

and musically will spread across the colored hemisphere,

in great handfuls the grasshoppers and grain and fountains

of the universal grain and the cornel tree, and venus

supreme venus and an inimitable light of iridium […]

A multi-linguist who worked in numerous languages in his native Italy before moving to Brazil in the 1950s, where he became involved with Concrete Poetry, which would deeply influence today’s Vispo movement, Villa was complex and original from the start. But reading chronologically through these poems, one sees a rapid shift toward the avant-garde. This development seems to have been at least partially sparked by World War II, as is evident in the brilliant poem, “1941 Piece,” which begins with a description that could be an ars poetica before moving in the second stanza to the cynicism that injects Villa’s otherwise intellectual poetry with feeling and humor:

It could be

that on any given

day air would travel

half-heartedly through the air,

maybe, but if Lake Garda fails to recover in time

all the dust eaten by cyclists in meaningless races,

& kilometers that don’t count, good for nothing […]

Villa’s poetry is often as ethereal as air blowing through air, or as he writes a few lines later, an “ephemeral vase of air.” But elsewhere in this poem, which stands out for its connection to historical events, Villa is stunning in his visual precision, as when he writes about “the breath…”

of foreign fodder, and the air filled

with a stew of local beer, and the change

of musical coins across the zinc counter, will touch

the firmament with frosted hands: and then

some agate marbles concealed in the panic snore

of those poplars will serve as lamps or blinds

When Villa writes about “the earthly dream / where the stones of Europe mature,” his vision of poetry in the midst of a World War crystallizes. This poem, which comments obliquely on the situation in Europe and Italy during World War II, is one of the last in the book that feels grounded in a physical subject. After 1950, when Villa published his collection Yeah but After, his poetry is a cacophony. This book and several following are printed horizontally rather than vertically, so one has to turn the book on its side to read the poems. At this point all the elements of language — its sound, its sense, and its image — become more pressing realities than the physical world.

In much of this mid-career poetry, Villa sounds like Fernando Pessoa if he could have written in all of his voices at once. This is code-shifting at its most vibrant:

seed in the tracks at the end of the line under the rotten ties

seed on the cobblestone of the capital

a grain on the sparrow’s tail

a proton (in the parlance of our times) a quantum bloated with shade

in the isotope

or (let’s suppose) a bacillus aestheticus subtillimus

in the wolf’s maxillary membrane or the anal

orifice of the whale

a seed (as we say around here) that leavens, of Justice […]

This is poetry that is smart, sensitive, and hard not to enjoy. When Villa is at his most inventive, he can swerve between the voice of Chaucer and a Milanese chancer in the dark alley of one line.

In Da Verboracula, published in 1981, drawings and charts mingle with words, vying for the attention of the reader, who is now also partially a viewer. The latter part of this collection feels utterly contemporary, as in still strange, like a combination of the New York School and the Language Poets. And here we see how Villa’s work developed along the same lines as the poetic avant-garde we generally consider American. This is from “Poetry Is,” written around 1989:

poetry is to forget

forgetfulness

poetry is to se-parate self from self

poetry is what’s completely left out

poetry is emptying without exhausting

poetry is constraint to the remote,

to the not yet, the not

now, the not here,

the not there, the

not before, neither not after,

nor not now […]

It is certainly Villa’s deep allegiance to the avant-garde and the experimental that have kept him in obscurity. Siracusa states that the poet is still relatively unknown even among Italian readers. His entrance into the canon enriches and complicates the way we think about poetry in both Italian and English.

Readers of Czech poetry will see a stylistic connection between Villa and the exiled Czech poet Ivan Blatný, whose late work also moves among several languages. As such, Villa — like Blatný — is a scholar’s dream, relatively untouched and truly complex. Contra Mundum is establishing themselves as a clearing house for Villa’s work, also publishing his Selected Writings as well as his translation of The Hebrew Bible.

It is important to note that passion shines through Villa’s great erudition and at times astringent avant-garde sensibility, and this is what differentiates him from many devoted practitioners of experimental anglophone poetry. His most familiar touch is a shock:

windows are a seed among headlights: and I

sow breath and great goodtime, and you

walking up and down the arteries of town;

and I make ragged comparisons, and you carry

the stingy and melancholy beauty within the red shade

of still being beautiful, a girl like a countryside;

and I know how to give forgotten compliments, and you move on;

and you think that one needs to watch what is needed,

and I think about shivering animals that will once again

piss close to the air like they used to; and you

make me a musical list of clothes to dry

in the generous and hapless air of our camporella.

Villa’s poems — complicated, confounding, exciting, rewarding — are a seed among eyes.

–Stephan Delbos