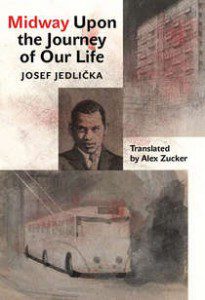

MIDWAY UPON THE JOURNEY OF OUR LIFE

Midway Upon the Journey of Our Life

A novel by Josef Jedlička

Translated from the Czech by Alex Zucker

Published by Karolinum Press

AT NINE THE ALARM CLOCKS start going off. Rise and shine for the night shift. Most of the children are already asleep. The women are coming home from the shops and canteens. In the doorway they share a fleeting kiss with their husbands, who smell of sweat, coal dust, and hydrogen sulfide.

I sit with my sticky fingers spread, watching the wintering flies settle onto them, and ponder the fact that there is barely coal for a week in the cellar. On the other side of the wall someone is playing Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture on an old raspy gramophone. Suddenly the door opens and in walks a woman wearing my mother’s wedding dress, a bouquet of Parma violets pinned to her bosom, with fishnet gloves and white leather boots. In her outstretched left hand she holds a blue porcelain candelabra ablaze with sallow tapers that singe a loose red lock of her hair with a sizzling crackle.

With a single abrupt gesture, graceful yet just hurried enough that it leaves a red scratch on her throat, she opens her dress and her tanned breasts slip out of the fine Valenciennes lace.

“We brought you some coal,” she says, beckoning me to follow her.

“It’s still a week till payday,” I say. “Not to worry, mon cher!” She presses my face to her warm, blue-veined breasts. “Poor Count de Lérouville is footing the bill, of course.”

So I walk out in front of the house and pour my last coins into the black-stained palm of the old wagonman: “Careful, friend, you don’t want to soil the lady’s dress!” The coal is deposited in front of the house: a big beautiful walnut of high heating value. The woman in the 1924 wedding dress lays the bouquet of violets on top of the heap and walks away. She walks away: “Adieu!” And as she turns to glance back one last time, the chill white of her throat shines from the furs around her neck. Meanwhile the “Marseillaise” is drowned out in the thunder of bells from the Cathedral of the Annunciation in the Kremlin. And after that, nothing but silence, a whooshing void untouched by even the most distant memory of applause at the Prague Spring concert in ’48 where one of my old friends lent me an uncensored copy of The State and Revolution. Then Páleníček performed the “Appassionata.”

The door opens by itself. I am tense, as though at any moment I might be caught in the act, once and for all. And the dark stream flows on through the factory gate, the loudspeakers blare a marching tune, the punch clocks ding, a red star shines above the cooling tower, and gray buses filled with prisoners quietly drive through the gate next door. We all wake to a shapeless night with the obstinate courage of despair, as if the dawn were never to come again. The workers begin their shift.

I’M NOT THE ONE CREATING the context. I’m writing an encyclopedia, giving testimony, hiding from the searching gaze of the policeman, in plain view of the world, on the second floor of this ramshackle building that any key can unlock. The point hasn’t been to interpret the world for some time now. The only thing that matters at the moment is fate. I am who I am — and you, you are the only ones I can call as my witnesses: you, men rocking a car on the clutch in the middle of a hill, you, stripped to the waist, giving a cheer as you bury gas pipe in the ground, you, women with old lady’s bellies, lining up for meat at five o’clock in the morning, you, starving, beaten, and tortured, coughing up the last drops of blood on the concrete bunkers’ moldy floors, you, drunken boasters formerly on a first-name basis with Frištenský the wrestler, you, technicians trained in the factories of Škoda and Siemens, earning a Brandenburg Concerto in a single man-hour — you, men with whom one day, it seems, one way or another, I will charge the bayonet side by side.

But who today can judge? Whose fault it is that we have forsaken each other? Who cast this spell on us that, sitting over a glass of beer, we read each other’s lips like the deaf for the lost words of fraternity and solidarity? To what beginnings previous to other beginnings must we return to rediscover a mutually intelligible code for the morning mist and the felled tree, for the swoop of a bird in flight, for the silence in a darkness teeming with little owls and barn owls?

Back in those days, in the age of innocence and hope, I lived in Prague with two sisters, the younger of whom, years later, I married. She still believed in those days that the cast-iron wheel with the handle in the operator’s cabin was what steered the tramway cars, clear evidence of how we unintentionally strip the world of its potential miraculousness with lyricism. The small flat was constantly full of people, coming and going as they pleased, since we kept the key under the mat. Cigarettes were still rationed, so we smoked them one at a time, passing them around the table and stuffing the butts into paper holders for later. We sat around the fold-up sewing machine till daylight, debating transition classes according to Marx and “The Part Played by Labor in the Transition from Ape to Man.” Also sexual issues and monogamy. We attended lectures, as long as they didn’t start too early in the morning, and locked ourselves in the bathroom to cram before exams. Whenever we had any loose change, it went into a common pool, so every now and then we could get drunk on fruit wine, 46 old-currency crowns a bottle. Sometimes we drank rubbing alcohol with grapefruit juice: The med students supplied the spirits, the juice came courtesy of the UNRRA.

Couples went into the entryway to neck. And then sometimes, toward morning, gone soft with fatigue and the sweet and ineffable certainty of God’s just kingdom, as the blackbirds out in the courtyard began to screech, we serenaded the stain-covered wall on the building across the way with “The Internationale.”

A milkman and his wife lived in the flat next door to us. Quiet, modest, considerate folk. The wife, tiny with black eyes, was pregnant, and sometimes she would come over to ask us for an aspirin. She contributed to our debates on Bertrand Russell without realizing it by showing off her blue layette to the girls. But then late one night she ended up giving birth to a little girl while I was shooting out the window at the wall across the way with a Belgian 9mm left behind in our flat by the Germans.

They weren’t so strict about firearms licenses in those days, despite the official position that arms in the hands of the people gave rise to tensions.

EARLY FEBRUARY WAS warm, with conditions particularly favorable for sighting a white horse between the fences, legs spattered black by the surface of an autumnal lake, or Icarus thrashing among the birches in Rieger Gardens. People stood long past midnight, overcoats unbuttoned, quarreling and arguing and debating on the sidewalk in front of the Melantrich building. We opened the windows at nighttime, enjoying the cool feel of the air on our naked bodies.

During those same days, somebody spat on a Czechoslovak Communist Party display case, just up the street from the Vinohrady market hall. The neighborhood agitprop committee framed the spit in blue glazier’s pencil and wrote in big letters: THIS IS HOW THE ENEMIES OF THE NATION AND THE WORKING CLASS FIGHT! It was clear that something had to happen, the time was ripe. Besides — we were the youth of the world.

Some of the people who came to see us in those days were Čestmír J., who went on to study medicine and I’m told now works at the psychiatric hospital in Bohnice; Miloš P., a German-looking blond with a German sense of order — for that matter he also had a German name — who even then already knew a lot about nuclear physics and relay computers; Dáša H., a very beautiful and very sad architect, whom years later I would bump into carrying blueprints for arched lintels, Corinthian capitals, and Byzantine colonnades; Vít Č., who no one yet knew would become an informer; Honza, refined and brilliant, with a personality so transparent he could barely be discerned by the naked eye, and his brother, the little boy who was ultimately destined to take the stand for Balzac, and Slávek M., the one who loaned me the uncensored edition of Lenin and who, having achieved the rank of doctor of philosophy, inherited from his father a working automobile; and Milan and a something or other Kuňa, and Irena and Božka and Fíma and Hanka and Soňa, and another ten or so whose names and faces I’m slowly forgetting . . .

Besides me and the two sisters studying medicine, we also had a subletter in the flat and, sometimes, K. the med student. The subletter, a former nun who had run away from the novitiate, would come home around eleven at night, fill the bath with hot water, and sit there steaming, hair up in a pink net, practicing her stenography on news briefs from Tvorba, the cultural review.

K. the med student, meanwhile, would spend whole days just sitting in front of the gramophone. We didn’t have too many records: “Rue de la Gaîté” by Nezval and Burian; “Ol’ Man River,” sung by Paul Robeson; “Sentimental Journey,” which wasn’t so associated with Viktor Shklovsky yet in those days; “Kanava,” a Russian folk song; Ravel’s Boléro; part of the third movement of Mozart’s Concerto in D Minor; and the Jewish prayer “El Malei Rachamim,” recorded by a Bulgarian or Romanian cantor named Katz, the only one to be saved right out of the gas chamber. Whenever he wasn’t asleep, the med student sat by the gramophone silently, and while the rest of us argued, pacing around the little room and pounding our fists on the sewing machine that served as our table, again and again he would play that despondent Jewish prayer, which at one point breaks into an Oriental-sounding falsetto chant. As soon as the record finished, he would very slowly rewind the device, change the needle, take his allotted three drags off the cigarette, and start the record over again from the beginning.

The day the Litvínov child left his footprints in the road’s concrete, the newspapers carried the news of the government’s resignation. It turned chilly and a damp snow began to fall. We went out into the streets of Prague and walked the city, heads held high, red stars on our lapels.

On the impassioned steps of the Rudolfinum, shivering in a light spring jacket, a young girl sat folding a paper airplane. In the great auditorium of the Philosophical Faculty, a Social Democrat gave a slap in the face to a short, lewd National Socialist, who even during lectures on Husserl’s Logical Investigations slipped references to his sexual problems into the discussion.

Maybe two days later, they called a meeting of the Party’s university committee at the Slovanský dům. We were advised to be on the alert. There was talk of a general strike and they were checking people’s IDs. A young editor from the Party daily Rudé právo stood on a chair in the back of the large low-ceilinged hall, speaking with his shoulder thrust forward. His coveralls were so new they hadn’t even been washed. Someone there told me a young poet had demanded to be let on national radio to perform his poem “We Recite Death” for the people. They denied him partly on principle and partly because he couldn’t trill his r’s properly.

By the time we came home it was very late. K. the med student was listening to “El Malei Rachamim,” and sitting on the couch next to him was a miner from Most named Joska, who was courting my future sister- in-law. To judge from the way he was bragging about his motorcycle exploits and the fact that he slept with an open knife beneath his pillow, he was very much in love with her. We informed him that the revolution was probably going to start the next day.

“Is that right?” he said, giving me a slap on the shoulder. “Hey, college boy, I’ll bet you can’t even ride a moped down a flight of stairs. I can and I’ve got a big bike, we’re talking DKW 500. OHV!”

We were thrilled to have him, and I shared in the excitement, since in those difficult days even the mere presence of a true representative of the working class was encouraging. I happily settled in on an improvised bed of couch pillows, and later that night the radio announced that Gottwald was going to speak on Old Town Square the next day. Joska and my sister-in-law were still leaning out the window sharing a cigarette when I fell asleep. They were talking about the shafts and open-pit mines here in the north, where they had met, about Most and Růžodol, about Komořany and Ervěnice, about the sites of my destiny that I had yet to glimpse, about gigantic conveyors towering over a barren range of slag heaps, the artificial landscape of my life, the world in its original form or finished once and for all, little by little, bit by bit, devouring everything.

____________________________________________________________________

JOSEF JEDLIČKA (1927–1990) was a Czech essayist and novelist. Expelled from Charles University in Prague after leaving the Communist Party, he moved to the border town of Litvínov, with his wife, a medical doctor, in 1953. In 1968, after the Soviet invasion and occupation of Czechoslovakia, he and his family emigrated to West Germany, where he worked as a cultural editor for Radio Free Europe in Munich. In addition to articles, studies, and reviews for Czech emigré journals, he wrote two works of fiction: the novella Kde život náš je v půli se svou poutí (Midway Upon the Journey of Our Life) and the novel Krev není voda (Blood Is Thicker an Water). Most of his life he was banned from publishing in his native Czechoslovakia. His works have been translated into German, Italian, and French.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

ALEX ZUCKER (b. 1964) has translated novels by Jáchym Topol, Petra Hůlová, Patrik Ouředník, Heda Margolius Kovály, Tomáš Zmeškal, and Magdaléna Platzová. He is winner of an English PEN Award for Writing in Translation, an NEA Literary Fellowship, and the ALTA National Translation Award. In addition to translating, he has worked in journalism and human rights. From 1990 to 1995 he lived in Prague, and he currently lives in Brooklyn, New York.