CEDAR AND HAMMER

“Who’s going for a smoke?” a nurse called down the corridor of the psychiatric ward. Of all the patients aimlessly wandering the limited space of the closed ward after dinner, only two men responded.

Doctor Kraus, a biologist from the hospital laboratory who had landed here again after a several-month binge of drinking. He was here for the second time and hated himself for it. After his first stay he left with some kind of hope and even someone waiting for him. Now the world on the other side of the white walls seemed more inhospitable than the barren landscape within him. Doctor Kraus was looking forward to a cigarette only for the cigarette itself, he did not want to smoke thinking about anyone, or look forward to a time when he’d smoke somewhere else, with someone else; actually he mostly wanted to smoke because they were allowed to.

The other smoker never worried about such things. Pavel Cervenka, called Paulie, a regular participant at the institution, was still a young man, a child of sorts with premature signs of age in his face, a child who acted as if he didn’t care much for the surrounding world, though he must have already realized that it was probably the other way around.

On the way to the improvised smoking section in the rear wing, they met the head of the department. Everyone including the nurses straightened up a bit, like soldiers when passing an officer.

“Mr. Kraus,” she called Kraus to the side, “if you are going to smoke now, please could you try to talk a bit with Mr. Cervenka.”

“About what, Doctor?”

“Just talk, about anything. I think he is suffering from a lack of human contact, and he’s a reasonably intelligent person.”

“I’ll give it a try,” Doctor Kraus nodded, suddenly pleased to have been entrusted with the task.

“Living in a shack, it’s not that great. But it’s still better than those homeless. Those guys act so cool, spreading their bags around for everyone to see, going around in rags on purpose, filthy, just so that everyone can see how bad they got it. I never understood that, as if I’m gonna brag I’m up shit creek, and lay down at people’s feet. What’s that prove when they sweep me into the sewer like some piece of garbage? I already know that people’re assholes, I don’t have to test it. I can be a fucking asshole when it comes to breaking bread, as they say. Everyone’s gotta look after themself that way and no baby bonnet with a pompom and filthy rags is gonna win anyone any sympathy. So I don’t get those hotshots at all.”

Paulie drew on his cigarette powerfully, as if any moment someone would take it from him. They sat on a pile of mattresses covered in waxy green canvas in the middle of an empty hall and ashed their cigarettes into a can. Exposed wires hung from the bare walls.

“They’re gonna fix this place up.” Paulie commented. “Whole thing’ll be new.”

“What’s it going to be?” Kraus asked, satisfied with how nicely the conversation was getting started.

“When they remodel it, there’ll be ICU units here. You know, Intensive Care, when they bring you in here delirious or unconscious, they won’t hafta drag you through internal medicine; they can shoot you up right here.”

“Did they bring you in here delirious?” Kraus asked and examined the dark red splotches around Paulie’s nose and eyes and the injury on his chin which was now slowly healing. He unconsciously ran his fingers over his own face, on which drinking had yet to leave such a signature.

“No, I came in here on my own. I simply picked myself up and came. To hide, know what I mean? I’d had enough of it, it was a nasty scene, I was already afraid that it would end bad, that I’d kill someone, or someone’d kill me. The head doctor even said it was good I came in, otherwise I coulda ended up somewhere else completely.”

“So what actually happened?”

“It was a very stupid day. After a stupid week and after a stupid month. Sometimes it doesn’t go your way. Like I said, we live in a shack, we have it over at the forest behind the train station, a so-called mobile home. We got it for two thousand off a guy I knew from the station, they towed it over there by tractor, over to that spot, so that’s where we are. We were better off when dad was still alive, and mom, obviously. Then we still lived in a building, until the owner fucked us out onto the street for not paying. We were paying before; dad had pretty good retirement, mom had something, too, well, we didn’t have work, me and my bros Charlie and Petey. We couldn’t manage it somehow, this fucking capitalism. You don’t have to work, so you don’t work, right? During Husak I did time for parasitism, and now parasitism suddenly doesn’t exist. We were on welfare, we should still be getting it, if only we’d go to the office, but who wants to listen to the crap they’re dishing out over there. Then my sis was helping us for a bit, she was living with some guy Jester, that’s his real name, dude, Aloise Jester, what a tragedy, they had a kid, so they were getting benefits on her, so we somehow scraped by. We also did odd jobs, helping out somewhere. I have a trade, I’m a mechanic. I went to vocational school. In the end I said screw it, no graduation, for me it was the studying, where you gonna study, at home the tv’s always on, my bros say let’s go for a beer, so better go for a beer. I took advantage of it, knowing how to weld, so I did some welding here and there, there’s good money in that, but when you’re wasted you’re not gonna be welding much. If I had money, I’d buy myself an arc kit and open a shop. But, fuck, who I am to have some workshop, like I’m some businessman. My bros, you know, my own bros would rob me of everything and sell it. Over there it’s better not to have nothin’, like that Saint Francis grandma’d always talk about, then you can go get wasted no problem, ‘cause when they turn out your pockets they won’t find shit anyway…”

Paulie let out a loud chuckle and immediately started coughing. That’s how it always is, Kraus said to himself, you want to laugh and you start to cough, as if your miserable lungs knew there was nothing to laugh about.

“We probably have to go back, right?” Paulie asked.

“No, we don’t have to. We’ve got time.”

“I know the doctor told you you should speak with me, so that I could, like, talk it out. That’s a therapy. So I’ll just jabber on, then. So, we ended up in the trailer, after my parents died, because the new landlord was smart, a sorta dupe outta left field, he didn’t argue with us, he just tricked us. That we should move out if we weren’t going to pay, after the death of our parents, right? He offered us money to sign a piece of paper about settlement, that he’d give us thirty thousand in hand. We haggled with him at first, about how the apartment has some kind of price, right? But then, you know, when it’s cash, we almost killed each other over it after that, afraid of how one of us might secretly sign and keep the money for themself. So Charlie, the oldest, said fuck, let’s go see the dude. The whole bunch of us, plus my sis with the kid and that Jester. So we signed, then for a week we boozed for all we were worth, then we got ourselves together and went to live at Jester’s parents’ cottage. That didn’t last long either, so we spent our last cash on that trailer. My sis’d already put the kid in a home, she’s probably better off there, and Jester disappeared, asshole.”

A heavy sadness fell on Doctor Kraus. He wanted to vent, too, but he never knew how. What was he supposed to say, that he was always caught in the same cycle – first abstinence, then controlled drinking, then uncontrolled drinking, and then crash. There’s nothing much to say about that.

“So he disappeared, the asshole…” the doctor tried to pick up the thread of the conversation.

“Yeah, then he gave another chick a kid somewhere in Bohemia; he even sent us a postcard, the cretin. Says, “Say hi to Evie.” Yeah, totally, like we’re gonna go down to the children’s home to tell Evie hi from you, idiot.”

“But now we’ve gotten sidetracked.”

“Yeah, we’ve veered off topic, as they say, right? So, the day I came in here. That day our brains were pretty fucked right from morning. Not mine, though, I drank a box of red wine in the morning and had a perfectly balanced level. Had it been up to me, I’d a sat in the trailer and listened to the radio. But Charlie, my older bro, he got that cypress into his head, saying how we should dig it up and sell it.”

“What cypress?”

“I don’t know, maybe it’s a cedar, that’s what dad said, cedar, when he planted it on grandma’s grave. A kinda ornamental tree. Pretty grown up, over a meter, meter and a half. It was at the cemetery on grandma’s grave, before you know it dad’s lying under there, not mom ‘cause we still had mom’s urn in the trailer, somehow we hadn’t managed to go by there. Charlie had a buyer for the cedar, some kinda asshole millionaire he was working for digging ditches. Guy built himself a house, a real mansion, the kind you make a path all the way up to and he was looking for ornamentals for the path. I told him, Charlie, he’s gonna send you to hell cedar and all; he needs small saplings, not a whale like that. But not him, he said a grown up one’d be better, more expensive, dummy. And we could bury mom’s urn there at the same time. And Petey, the youngest, he was raging about those covers again. Seriously raving mad. You know on the streets down below the hospital, those cunts changed out the iron manhole covers for concrete ones. Well, and because Petey and his buddy who had a cart would go rip ‘em off and sell ‘em for scrap. And you may as well stick the concrete cover up your ass ‘cause no one’s giving you shit for that. So he was raving about how he was gonna go down there and smash apart the new ones, so that those cunts could, like, see that that’s not a solution.”

“I’ve tried that one, too,” sighed Doctor Kraus. “I also wanted to demonstrate that that’s not a solution.”

He recalled one conversation with the head doctor:

You see, a person needs a solution, they also need someone to be with, in good times and bad. Especially in the bad, but then everyone looks at you like a downer cow.

I see your point Mr. Kraus, but you have to understand that a person must take responsibility for his own life and not expect anything from others.

Not even from those closest?

Especially not from them. It’s not easy for me to say, but it’s also my personal experience, and I’m still a bit younger than you. If you remain fallen, you are putting yourself into the hands of…

Beasts!

Beasts maybe, at that moment you will certainly see them like that.

And how do you see them?

Me? She smiled bitterly, such a pretty, slightly gaunt, dark woman. I see them as normal people. At the word normal, there was a small curling of her lip. Normal people who want to withdraw from the reach of danger and pain. And if you are that danger and pain, they will shrink from you, that’s only natural.

But every person can be pain and danger for others.

Look, we are not saviors here. We are only trying to regulate your personality a bit so that you don’t threaten yourself or your surroundings. You’ll see though, when you’re able to find some relief, you’ll start perceiving things differently.

“You chewed it over yet?” Paulie interrupted the flow of his thoughts.

“Yeah.”

“It’s good how we’re running things here, I ramble on, you think about your own stuff, but I don’t mind. So we went to get the cedar. You would not believe what long roots that tree has. We didn’t even have a proper hoe, just some kinda iron clamp. We couldn’t see shit at night. Pretty much killed ourselves. The roots went under the curb all coiled up like a snake. I tell you, that grave did not look even half as good after that, hole like a grenade went off. We were all scratched up from the needles. We also kinda cracked the cedar as we were tearing it out. We were also afraid the gravedigger’d come out. I mean, I was mostly afraid for him ‘cause my bros were so pissed off, mainly Petey, that he probably woulda cancelled that gravedigger. He was sensible not coming out. I know he was just sitting there in that morgue a his, but fucking quiet as foam. So then we got the cedar and went.”

“And what about your mother’s urn?” Kraus asked.

“Oh, mom, we almost completely forgot her. I went back over there later and dug her into the hole the cedar left. Then I piled up some dirt so it wouldn’t be noticeable.

Then we went to see moneybags. Well, me and Petey stayed back at the construction site and Charlie went with the cedar to ring the bell. The guy came out with a Doberman on a leash. Then they argued, told him to come back in the morning. So my bro threw it down at his feet. The guy just about set his dog on him. Well for a hundred, then, he says. My bro wanted a thousand. The guy cursed, calling him a thief. Charlie screamed at him again about having built everything from stolen material, which is true. Then Petey starts saying how he’s gonna go cancel the guy and his dog, which was barking like crazy. The neighbors started turning on their lights and opening windows. So then the guy gives him four hundred and we get outta there quick. Petey swiped a sledgehammer there, a twenty-two-pounder, it weighed twenty-two pounds, you can believe him on that, he knows how much iron weighs. He took it right out of a crate the stoneworkers had their tools in.

We went to a bar and drank through that money in spirits. We don’t normally drink spirits, just brews, but that time we were so screwed up that we’d lost all sense. Then we borrowed even more money on the hammer, but Petey needed it, so we stole it back from the bar, bartender was wasted, too.

My sis came with some guy she knew, she got hammered and cried about having her kid in the home, and I told her that she was probably better off there. Then Petey chucks the friend of hers out, he’s jealous over her, and she said that the guy was an asshole anyhow, but that she still got some money off him, so we drank through that completely. It was a valley of tears. Charlie kept grumbling that the cedar was worth at least two thousand, that he’d seen it in the garden center where they went for materials, two thousand for such a tiny plant, and ours, planted by daddy even, that’s what he said, daddy, how many fists in the face he’d given daddy, and then daddy this, and how we buried mommy. Yeah, we cried like crocodiles that night, like crocodiles. And I was already pretty lubricated, it was starting to hit me. I told the waitress she had a nice pussy and that I’d fuck her, and she said she wouldn’t serve us anymore, so Charlie went to iron things out at the bar and nearly beat up the manager. In the middle of that my sis whispers to me that she’s afraid of Petey, because he’s always after her. And I told her I’d protect her, but I’d be no match for Petey, he gets wild fighting, as we saw later. In the end I was completely fed up with my whole family.”

“You bet, family,” Doctor Kraus added quietly.

“You probably don’t have it easy either, doctor, and you’re even graduated, not like us born retards. They say your woman packed your bags, least that’s what they say here. Forgive me if I offend.”

“That’s fine,” Kraus waved his hand.

“Maybe we should swap parts, the roles, as the psychologist says, when we do that crap in the community. But somehow it actually helps me, they’ve got it figured out here, worse when you get outside, doesn’t work there.”

“Better finish it up,” the doctor was horrified to find that he actually had nothing to say for himself, no testimony. He felt like after a car crash, you don’t know what’s broken and what’s torn off. A kind of sack of bruised things hanging off you and you only feel that you can’t carry it, but you must. As if after the accident, instead of bandages and stretchers, they said, pull yourself together and don’t dirty the car. And you would walk to the bus and catch the blood with your hands so you didn’t smear people’s coats. The normal people who are trying to get out of reach of pain, Mrs. Doctor.

“So finish it!” he said a little angry.

“Sure, it’s all the same to me. So we split the bar. Sis still had some money squirreled away, she’s an incredible squirrler, to buy another bottle for the trailer. But Petey’d have it no other way but to go for those covers, that we had to show them that they hadn’t yet beat us with their concrete.

So Charlie went with sis back to the trailer and we went for the covers. Fuck me for not going home, shit, bed, radio, cigarette, what else could I want. But we’re such hardheads, we got that from dad, whenever he’d get mad he’d throw a cinder block to the fourth floor…no, I’m exaggerating, to the second at least, but he was a nice person, he went to work, to church. We’re all baptized. You baptized, too, doctor?”

“I think I am.”

“Well, guess that didn’t protect us much.”

“Baptized isn’t holy.”

“You’re right, we weren’t holy. We got to work from the hospital down and one cover after the next always cracked nicely on the second blow.”

“And didn’t it occur to you that someone could break their leg on one of those uncovered sewers?”

“They should look where they’re going, idiots. But there’s a hospital there, right, so they’d plaster it up for them.”

“You’ve got an answer for everything, don’t you?”

“If I didn’t, I wouldn’t be here. Like that night. Petey was on fire. Here and there he’d also smash a parked car, and people are just not going to put up with that. Somebody called the police. The sirens came and I knew it was bad. I still managed to take the hammer from Petey, otherwise the police choir woulda suffered some casualties. Then they’d be handing out little flags to their widows like in American movies, saving private, what was his name, doesn’t matter, he fell while defending his country. I threw that corpus delicti over the fence to the hospital, and when I saw my bro fighting with them I hit the road, it wasn’t about anything anymore. He was going to do hard time, he was on parole. At least he’d leave our sis alone, he seriously was climbing onto her. So I actually saved her in the end.”

“Okay, and then what?”

“Then I came to the front desk, here at the hospital, and fell right over like a board and stayed down, it was the only place they couldn’t accuse me of anything. Lying like a board. That was no great hardship for me ‘cause I was absolutely shattered by that time. So they took me into the ward, zero point three I don’t know how many percent and lights out. I’m warm here.”

“Seems you managed that neatly.”

“What was I supposed to do?”

“I think that Pavel is, in his own way I mean, quite alright,” Kraus told the head doctor when she visited him later in the evening in his room.

“You’re basically right,” she answered carefully, “now it’s about you finding your own way.”

_______________________________________________________________________

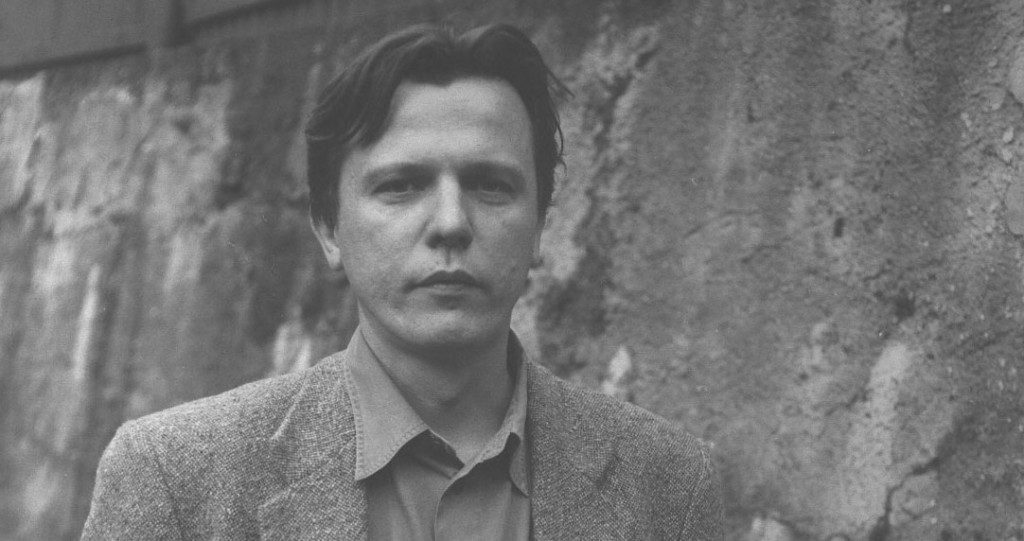

JAN BALABÁN (1961-2010) was a Czech, especially Ostravian writer, journalist and translator. He studied Czech and English Languages at Palacký University, Olomouc. After travelling the United States and Canada, he interned at King’s College in Aberdeen, Scotland, later working as a technical and then freelance writer and translator of English writers such as H.P. Lovecraft and Terry Eagleton. He published nine works of stories, fiction and narratives, including Možná že odcházíme, which received the Magnesia Litera Prize for prose in 2005.

_______________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

NATHAN FIELDS has translated contemporary Czech literature into English in the form of novels, short stories, screenplays and scripts, and poetry. He has received praise for his translations of Jan Balabán (Zeptej se táty) as well as works by Jáchym Topol, Edgar Dutka, Petra Hůlová and Miloš Urban. With a degree in Literature and Writing, he has been teaching English and translating in Prague for over a decade.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Jan Balabán:

Short story in Words Without Borders

Short story in Transcript