A DILEMMA

(an excerpt)

A Dilemma

A novel by Joris-Karl Huysmans

Translated from the French by Justin Vicari

Published by Wakefield Press

i

In the dining room, which was furnished with an earthenware furnace, cane chairs with twisted legs, and an old oak sideboard, made in Paris at Rue du Faubourg Saint-Antoine, that held behind glass panels gold-plated chafing dishes, champagne flutes, and a complete white porcelain dinner set edged with gold that had never once been used—there, beneath a photograph of Monsieur Thiers, weakly lit by a hanging ceiling light that glowed down on the tablecloth, Maître Le Ponsart and Monsieur Lambois folded their napkins, signaled with a glance for the maid to bring them coffee, and fell silent. After the girl left, Monsieur Lambois opened a rosewood cellarette, glanced suspiciously at the door, and then, apparently reassured, spoke.

“See here, Le Ponsart, my friend,” he addressed his dinner guest, “now that we’re alone, let’s talk a bit about what’s on our minds; you’re a notary; where exactly do we stand as far as the law’s concerned?”

“Exactly here,” the notary answered, taking a penknife with a mother-of-pearl handle out of his pocket and paring the tip of a cigar. “Your son died with no heirs; no brother, no sister, no progeny. The little he had from his late mother must, by the terms of Article 746 of the Civil Code, be divided equally between the paternal and maternal ascendants; in other words, if Jules didn’t make a dent in his capital, you and I get fifty thousand francs apiece.”

“Fine. But we still don’t know if the poor boy had a will bequeathing a portion of his assets to a certain someone.”

“Yes, that’s the point that needs some clearing up.”

“So,” Monsieur Lambois went on, “assuming that Jules held on to all his hundred thousand francs, and died intestate, how can we get rid of that creature he was living with? And do it in such a way,” he added, after a moment’s thought, “that she won’t attempt to blackmail us, or pay us a scandalous visit that would compromise us in this town.”

“There’s the rub. But I have a plan: I know how to get rid of that scamp, quietly and without much expense.”

“How much do you mean by ‘much expense’?”

“Heavens—a fifty at the most.”

“But not the furniture?”

“Of course not the furniture . . . I’ll pack that up and have it all shipped here.”

“Perfect,” concluded Monsieur Lambois, pulling his chair up to the stove and wincing as he stuck out his gout-swollen right foot within heating range of the furnace’s open door.

Maître Le Ponsart sipped a digestif. He savored the cognac, and whistled through his lips, which he puckered like a rosette.

“My word,” he said, “is this that old cognac from the uncle?”

“Yes, there’s nothing like it in Paris,” Monsieur Lambois stated categorically.

“Indeed!

“But look,” the notary went on, “even though my position’s clear, since we can’t be too careful, let’s review everything we know about this little missy before I leave for the capital.

“No one knows who her parents are, we don’t know the circumstances under which your son fell in love with her, she possesses no education whatsoever—that is clearly evident by the grammar and penmanship of the letter she sent you and which, heeding my advice, you were right not to answer;—in short, we don’t know much.”

“And that’s everything—I can only repeat what I’ve already told you; when the doctor wrote me that Jules was seriously ill, I got on the train, arrived in Paris, and found the hussy installed in my son’s home and nursing him. Jules assured me that the girl worked for him as a maid. I didn’t believe a single word of it, but I obeyed the orders of the doctor who told me not to upset the patient and didn’t argue the matter; as the typhoid fever was growing worse with each unhappy hour, I stayed on, tolerating the presence of that phony maid to the very end. She did present herself very respectably, I have to give her that; then the removal of my poor Jules’s body had to be done without delay, as you know. Busy with purchases, errands, I had no occasion to see her again, and I hadn’t even heard tell of her until that letter arrived in which she declares that she’s pregnant and asks me, as a favor, for a little money.”

“Prelude to blackmail,” the notary said, after a pause.

“As women go, what’s she like?”

“She’s a tall, beautiful girl, a brunette with fawn-colored eyes and straight teeth; she speaks very little, and her discreet and artless demeanor leads me to think she’s a crafty and dangerous person; I fear you have a tough opponent, Maître Le Ponsart.”

“Bah, bah, that little hen would need strong teeth to bite an old fox like me; anyway, I still have that police commissioner friend in Paris who can help me if necessary; as crafty as she may be, I have a number of tricks up my sleeve and I’ll bring her to heel if she makes any fuss; in three days my expedition will be over, and I’ll come back and claim from you, as a reward for my successful endeavors, another glass of this old cognac.”

“And we shall drink it with happy hearts!” cried

Monsieur Lambois, momentarily forgetting his gout.

“Ah, that pea-brained boy,” he went on, speaking of his son. “To think he’d never given me any trouble. He worked conscientiously at his studies, passed his exams, even lived perhaps a bit too much like a lone wolf, unsociable, no friends, no companions. Never, and I mean never, did he run up any debts, and then, all of a sudden, there he is, hooked by a woman that he fished out of who knows where. It baffles me.”

“It’s the way of things: children who are too precocious come to bad ends,” declared the notary, standing in front of the stove and lifting the hem of his frock to warm his legs. “In fact,” he continued, “the day they catch sight of a woman who strikes them as sweeter and less brazen than the rest, they think they’ve found the very magpie’s nest, and all else be damned! The first one to come along hoodwinks them and they just don’t care, even if she’s silly as a goose and clumsy to boot!”

“Say what you like,” replied Monsieur Lambois,

“Jules was not the sort of young man to let himself be controlled that way.”

“Heavens,” the notary concluded philosophically, “now that we’ve gotten on in years, we forget how easily young men let themselves get sweet-talked by a petticoat, but if you think back to the days when we were more spry, aha, the skirts turned our heads, too. You talk, but you never gave up your share to other men, did you, my old Lambois?”

“Certainly not! Until we got married we had our fun like everyone else, but in the end, neither you nor I were ever foolish enough to fall—let’s call a spade a spade—into concubinage.”

“Obviously.”

They grinned. The flush of their youth came back to them, leaving a bubble of saliva on Monsieur Lambois’s blubbery lips and a glint in the old notary’s pewter eyes; they had eaten well and drunk a vintage wine from Les Riceys, a purple-colored wine that had lost some of its alcohol content; in the warmth of the enclosed room, their heads flushed in regions long dormant, their mouths watered, excited by the entrance of that woman whom they could now ungirth, without any witnesses, at their leisure. Little by little, they worked themselves up, repeating twenty times over their tastes in women.

They only appealed to Maître Le Ponsart’s senses if they were short and plump and lavishly dressed. Monsieur Lambois preferred them tall, on the thin side, and without expensive adornments; he prized refinement above all else.

“Bah! Refinement’s got nothing to do with it. Parisian style, yes,” said the notary with smoldering eyes; “What’s most important is to not have a wooden board in bed.”

And he probably would have expounded further on his sensual theories, but a cuckoo above the door, noisily chiming the hour, cut him short. “Goodness,” he said, “ten o’clock! Time for me to go home if I want to be up early enough tomorrow to catch the first train.” He put on his coat; the antechamber’s cooler air chilled the ardor of their nostalgia. The two shook hands, uneasy now that their visions of women had evaporated, and felt their hatred grow toward that stranger with whom they intended to wage war, thinking that she was bound to hotly dispute an inheritance rightly entitled to them by the Code, that judicial monument which they revered like a tabernacle.

____________________________________________________________________

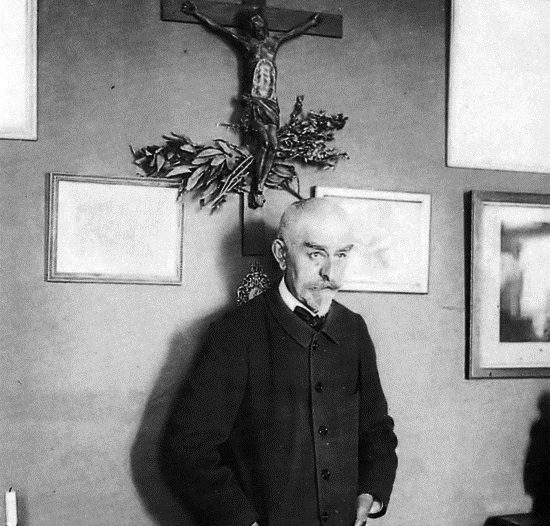

JORIS-KARL HUYSMANS (1848–1907) explored the extremes of human nature and artifice through a series of books that influenced a number of different literary movements: from the grey and grimy Naturalism of books like Marthe and Downstream to the cornerstones of the Decadent movement, Against Nature and the Satanist classic Down There, along with the dream-ridden Surrealist favorite, Becalmed, and his Catholic novels, The Cathedral and The Oblate.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

JUSTIN VICARI is the author of several books of literary and film theory. His first book of poems, The Professional Weepers (Pavement Saw Press, 2012), won the Transcontinental Award. He has also translated Paul Éluard, François Emmanuel, and Octave Mirbeau.