Delicious Foods

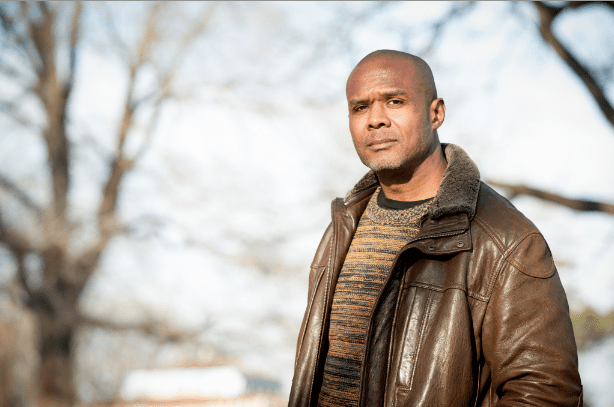

by James Hannaham

Little, Brown and Company (2015)

384 pages

The opening scene shows us Eddie, who just got his hands chopped off, speeding away in a car – driving with his bloody forearms – fleeing his tormentors. The tormentors? They run a secret slave-labor farm deep in the backwoods of Louisiana, where his mother Darlene is still trapped. Not long after, we hear from the third main character who is, quite literally, crack – the drug, given a voice and some serious storytelling prowess.

Is this an avant-garde pilot for the next hit tv series, à la Breaking Bad or True Detective? For now – and maybe not for long – no. It’s James Hannaham‘s new book Delicious Foods, and for all the sensational elements listed above, the book’s many strengths lie in its sensitivity and subtlety, as well as its force.

As in his first novel, God Says No, Hannaham serves up a cast of complex characters who are themselves surprisingly un-extraordinary. And, as in his first novel, Hannaham anchors his tale with a heartbreaking, tender protagonist. But being black in the American South tends to lead, almost by default, to extraordinary situations – many of them not at all tender, and some tragic.

“Everybody black knows how to react to a tragedy. Just bring out a wheelbarrow full of the Same Old Anger, dump it all over the Usual Frustrations, and water it with Somebody Oughtas,” Hannaham tells us when Eddie’s Aunt Bethella discovers the fresh stumps of his arms. “Then quietly get some globs of Genuine Awe in a circle around the mixture, but don’t call too much attention to that. Mention the Holy Spirit whenever possible…”

But the tone here is different than in God Says No – there’s an urgency, achieved through a brilliantly structured manipulation of time. The prologue – starting in the present with Eddie’s handless nighttime escape – speeds up by days and weeks, then by months and years, steadily noting his marriage and the birth of his son, with the same unobstructed pace in which it tells of Eddie’s casual encounter with a waitress in a diner. That mundane encounter, in turn, leads to a carpentry job – the “Handyman Without Hands.” The novel then jumps back and forth in time, adding a sense of inevitability to what we understand to be a cause-and-effect sequence of conflicts – physical (how did Eddie lose his hands?), psychological (what got Darlene hooked on crack?), and social (who killed Eddie’s father, the civil rights activist Nat Hardison?).

These conflicts all lead to Delicious Foods, the name of the slave-labor farm in the middle of nowhere. Its addict employees try to figure out where on a map they are, but even the management seems content to be lost. When Eddie enters the house of Delicious’s master-owner Sextus Fuslier, he finds “a disintegrating old-fashioned globe on which somebody appeared… to have drawn by hand the right half of America, given up after Louisiana, and started scribbling.”

References to the outside world appear only in fragments – a headline about the Viking 2 spacecraft, a Public Enemy lyric, a reference to “the situation in Rwanda” – intensifying Eddie and Darlene’s sense of isolation. No matter where they go, from small towns in Louisiana to the streets of Houston, they find themselves in a place that defies change as something irrational and impossible.

Change is a topic that Scotty, the Richard Pryor-like voice of crack cocaine, knows well. When Darlene thinks about escaping the Delicious Foods compound to find a better life, Scotty pipes up (terrible pun intended):

“What jobs she gonna get anyhow? Looking that type of change in the face could terrify the shit outta people who ain’t had them problems.”

The narration of Scotty is where the novel really takes flight. (It’s also where I can hear a tv producer stepping in with That’s too crazy! Can’t we just make it one of her friends?) Scotty’s brutal jaded humor is a perfect counterpoint to Eddie’s sincerity and struggles through childhood. It’s a daring choice that, in fact, makes perfect sense – in the “Scotty” chapters the story might involve Darlene, but she’s not in charge. It’s the drugs talking. By using Scotty’s perspective – ageless, bodyless, wise – we see the nuance in a battle for rationality:

“Love’s a mother to start with, so when sonofabitches start fighting over who love who more, and tryna say that this action you done today gotta line up with that verbal statement from yesterday ’bout how much you loved somebody, and they pull out they love-o-meters and start measuring shit out to infinity, I get pissed. Me, I think people could love me, or somebody like me, and still show they obligations to the other people in they life as number 2 and 3 and 4 and so on down the line and it ain’t no thang.”

The genius of having Scotty tell an addict’s story is that so much of it is less their own story than his. Darlene and the addicts of Delicious Foods are broken people. Even when they’re not high – especially when they’re not high – Scotty talks even louder:

“Not to be egotistical or nothing, but I am irresistible.”

––––

At the beginning of North Toward Home, Willie Morris describes the hill-country of Mississippi:

“On a quiet day after a spring rain, this stretch of earth seems prehistoric – damp, cool, inaccessible, the moss hanging from the giant old trees…. you may feel you are in one of those sudden magic places in America.”

It’s a sentiment that Breece Pancake echoes in his short story “Trilobites,” feeling a connection with the more ancient, fossilized history – beyond the last 400 years. Pancake’s story concludes with him walking through the night in the fog:

“I walk, but I’m not scared. I feel my fear moving away in rings through time for a million years.”

But these are white men, and the peace and magic they find in the Southern landscape (proudly resisting change since the Jurassic!) contrasts bitterly with the experience of Darlene in the company of Scotty.

“In elementary school, her science teacher had taught the kids that long ago, when the continents was one continent, the middle of the U.S.A. had sat at the bottom of the ocean, and sometime Darlene find herself imagining that it still there, with the whole of the wind turning into a deep, drowning liquid, with catfish and octopuses skimming all around hills made of sand and seaweed, and prehistoric fish feeding on the naked limbs of dead trees that be pushing up out the dirt…”

Her only escape is to look up, guided by the dreamy, incomplete science of her star-named co-laborer Sirius B, and the velvet voice of Scotty.

“At the end of every day, while the horizon going black and we watching the stars and planets blink above the smoke from the planes, she thinking ’bout Eddie, and ’bout Sirius, and ’bout the billions of years since the water had drained off, and the billions that’s gonna come, and ’bout how small her world had become. Without putting no words on them thoughts, she got pretty sure that she ain’t matter, and she did break out running, but she ran back toward all the things in life she knew for sure – especially me.”

Scotty also lets us enjoy bashing the South, which I, as a native Tennessean, can’t help but appreciate:

“Texas was stupid, I’m sorry. Fat sunburned gluttons and tacky mansions everywhere, glitzy cars that be the size of a pachyderm, a thrift store and a pawn shop for every five motherfuckers. Fucking limestone! Whole state and everything up in that bitch made of limestone. Damn strip malls look like they done come right up out the ground. Upon this rock, I shall build my strip mall.”

As much as Delicious Foods rages, it never comes off as being preachy (if anything, the Christian Bible is referred to here only as “the book,” and usually in relation to its irrelevance). Similarly, in dealing with the history of slavery and racial prejudice, Hannaham deftly avoids being heavy-handed. Darlene and Eddie are warned early about a litany of injustices, then brutally experience many more themselves, but the depth of these characters – and the way in which we jump around from their perspectives to Scotty’s – keeps us flying along, without fear of bumping into stereotypes or maudlin melodrama.

Returning to my fears of commercial tv, I think a bad producer could be tempted to look at the horrors of the Delicious Foods farm as fodder for the next Eli Roth torture-porn, because shady labor camps like this have been scandalously discovered around the world (Australia, Czech Republic, etc). And while there is a racial component to these real-life camps (exploited Bulgarians, Vietnamese, etc), it is a wholly different scenario than that of African-Americans in the Deep South.

This story isn’t just about where your food comes from, or about the perils of drug addiction. Hannaham is showing us an ongoing Great Migration. There are echoes here of Isabel Wilkerson’s monumental chronicle The Warmth of Other Suns – following Eddie’s Aunt Bethella out of Louisiana, then to Houston (Scotty again: “of course, moving to Houston don’t never solve nobody problems”), and then up the Mississippi River to Minnesota. And there’s a similar resonance with Wilkerson’s stories in seeing Nat and Darlene’s fight for civil rights trounced by small-town evil, then buried under addiction.

But Hannaham also shows us that the mentality that justified slavery is the same mentality that today justifies illegal immigrants working in the kitchen for $5 an hour off the books. The flawed logic of the 1850s is exactly the same as you might hear today: It’s just the way the system is… or If I pay them I’ll be out of business… or They left a worse situation behind them… or So and so treats his workers very kindly…

The root of this mentality is exposed near the end of the novel by Sirius, who speaks to the history of this unchanging code:

“…most often people who have power turn their story into a brick wall keeping out somebody else’s truth so that they can continue the life they believe themselves to be leading, trying somehow to preserve the idea that they’re good people in their small lives, despite their involvement, however indirect, with bigger evils.”

Perhaps as a testament to hope, Sirius is the one who escaped the farm.