FARABEUF

(an excerpt)

Farabeuf: or, The Chronicle of an Instant

A novel by Salvador Elizondo

Translated from the Spanish by John Incledon

Published by Ox and Pigeon

Certain looks weigh upon the conscience. It is curious to feel the weight a particular look can have. It is interesting to see how the dire need to retain a memory is more potent and more sentient than silver nitrate carefully spread on a glass plate and exposed for a fraction of a second to light penetrating a moderately complicated combination of prisms. That light, like the light of memory, is materialized forever in a moment’s image. A blurred image, the true meaning of which, understood in solitude and in silence, would make you cry out in the night. That cry is the mere mask of your real pain. An acute pain, a thousand times more acute than the dismemberment they slowly, like ice melting in the sun, but suddenly, like the convulsions of a dying man, perform on the body of the torture victim.

“Photography,” said Farabeuf, “is a static form of immortality.” Then he carefully deposited the old black leather case on the marble table. For an instant, his eyes alighted on the painting which hung before him, but the allegory represented there did not seem to catch his attention. He glanced at the nude woman who appeared at the right side of the painting, but lowered his eyes in the very act and continued carefully removing the instruments wrapped in small linen bandages from the bottom of the old black leather case.

You had stopped. What was unexplainable was that in spite of your immobility at that moment which occupied no space in the extension of time (a concrete, irrefutable act, since the stillness is the one fact that is absolutely certain), an unmistakable movement occurred, for when you stopped suddenly, someone (perhaps it was I myself) clearly heard a sound like the one made by a wooden planchette slowly sliding over a board, impelled by an imponderable force, driven by a secret desire, moved by the longing to ascertain more than to inquire. Or like the sound made by three coins striking a table. That sound was the indisputable manifestation of a movement, the only one existing there in the stillness and silence which seemed to engulf everything.

“Photograph a dying man,” said Farabeuf, “and see what happens. But remember, a dying man is a man in the act of dying, and the act of dying is an act that lasts but an instant. Therefore,” he continued, “to photograph a dying man, the shutter of the photographic apparatus must open precisely at the only instant when the man is dying, that is to say, at the exact instant the man dies.”

You are, as we all know, dear Master, the author of this small précis which has been the topic of such heated debate in the professional circles of your specialized field. In truth, it is a disturbing little work. The Faculté, of course, has not involved itself at all in the scandal it has produced. The men of letters, particularly the Dreyfusards, are the ones who have hurried to drink at the fountains of the unhealthy wisdom that you, dear Doctor, not without a certain ingenuity and humor, have cultivated in the wasteland of medical philosophy at the present time. Your exhaustive analysis of Leng-tch’é, with the magnificent photographs that accompany it—the result, as we all know, of your technical expertise in the art of Daguerre—will in the years to come undoubtedly reserve for you a place of honor in the history of medical curiosities. In fact, not since the courses of the great Claude Bernard, which led to the Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine, has there emerged a theoretical text as important as yours, at least not from our Faculté. The indiscreet use that the literati have made of it is only to be lamented. Were it not for this, dear Master, your candidacy would most certainly be assured.

What awaited us beyond, at some point in the future, gave the walk by the edge of the sea a special meaning. In order to remember it, we would need to have held hands. This would have given our experience the immediacy that things have in the popular imagination, in the minds of those idle people who strolled distractedly along the quay and who, without meaning to, occasionally glanced at us as we strolled along the sand with the waves breaking by our side. To be real, we must be just as those strangers imagined us to be. Nevertheless, we walked apart. You went ahead of me. That is why you could run without my being able to stop you. For a moment I thought that the magnitude of the grayish sea had overcome you and that you were trying to move away from the pounding surf. But then I realized you were actually fleeing from me, fleeing from my proximity which troubled you so. You began to run. You did not notice the boy building a sandcastle as you passed him. It would have been in your nature to have stopped, to have patted him, to have given him some words of praise. At that moment you were someone else whom I did not know. That is why, as we passed the woman dressed in mourning, you made some comment which I could not hear clearly, and you took no notice of the dog that followed her. I would like to have stopped you as you ran from my side, but just then you yourself stopped abruptly. You kneeled down among the round pebbles on the beach and found a starfish, which you showed me, saying, “Look, a starfish.” That putrid object, delicately held between your fingertips, infected you with anxiety, as though your hands had touched a corpse before your heart had realized it. Remember . . . ?

There is a curious element to all this, an effect that cannot be explained by even the most elaborate theory of photographic technique. When we climbed the cliff and sat on the rocks to watch the flight of the seagulls and the pelicans, I took a picture of you. You were leaning against the rocks worn away by the fury of the waves. It was just a snapshot of an undoubtedly banal ocean view, with your face in the foreground, looking as if you were asking some unimportant question. Why then, when the film was developed, did you appear to be standing in front of the window in this room?

____________________________________________________________________

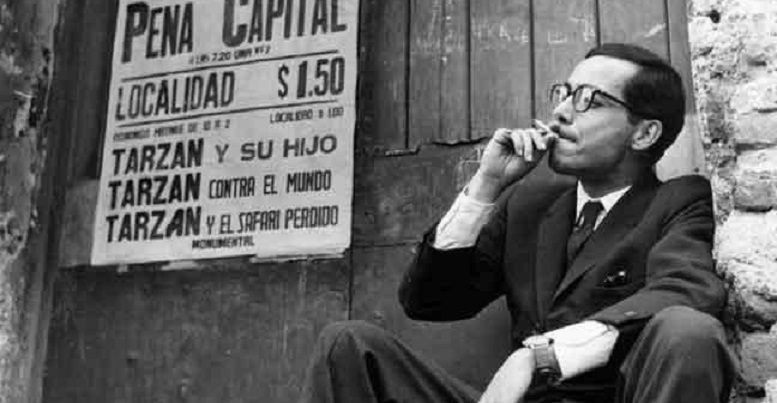

SALVADOR ELIZONDO (Mexico City, 1932—2006) was a novelist, poet, and playwright. His work rejected the magical realism so popular in his day, opting instead to incorporate cosmopolitan influences from Europe and elsewhere. He received the Xavier Villarutia Prize for the novel Farabeuf, or, The Chronicle of an Instant.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

JOHN INCLEDON teaches Spanish, Latin American literature, and translation at Albright College. He has published articles on Borges, Cortazar, Carpentier, and Paz. His translation of Farabeuf was the first runner-up in the American Literary Translators Association’s annual contest.