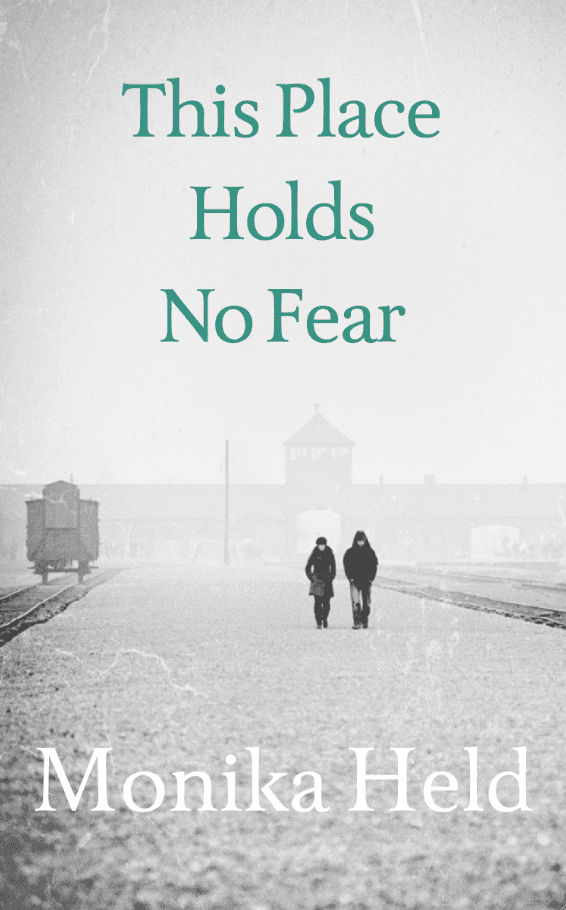

THIS PLACE HOLDS NO FEAR

(excerpts)

This Place Holds No Fear

This Place Holds No Fear

A novel by Monika Held

Translated from the German by Anne Posten

Published by Haus Publishing

They sat in Café Stern on the evenings of the 53rd, 54th, and 55th days of the hearings. He told Lena, as if it hardly mattered, that he had been divorced for five years, and that he had a daughter in Vienna – Kaija. He had lost contact with her. So he wasn’t completely free, but he wasn’t really attached, either. And you? Lena answered tersely: I live in an apartment alone. I don’t have children. I have an attachment named Tom. On the 56th day of hearings Heiner walked through the city for a whole hour, led by Lena’s hand, and he still wasn’t sure whether the hand was only meant to protect him or whether her heart was pounding like his. He gained confidence, ventured a few shy glances at people and stopped thinking that he had seen every face before. When he appeared in court for the second time, Lena sat in the gallery, listened to the judge’s questions, and heard Heiner’s clear voice responding. Just knowing she was there gave him strength, but he still felt as if he were walking on a wire over a deep canyon. He couldn’t allow himself to fall, not again. He had to simply remember, without seeing any of the images that went along with his memories. Evidence in the eyes of the law: that was all that mattered. Murder, even the murder of thousands, had to have a place, a time, and a date. Where had he seen Klehr? In Block 20? Why there? He worked in Block 21. How did he get from Block 21 to Block 20? Which door had he used? The one on the long side or the one on the short side? Or on the gable side? In what room did Klehr kill people? Was it to the right of the hallway or to the left? Was Klehr alone or were there prisoners in the room? Did Klehr wear an apron during the killings, or a lab coat? Was it purple, red, white, or yellow? Did he have a needle in his hand when the witness saw him? Was it in his right hand or his left? Did the witness see the people who were killed? How many were there? Was it closer to twenty or to a hundred? And where were the bodies taken afterwards? Was there a door between the hall and the room, or just a hanging blanket? How often did killings take place there? Once a week, or every day?

He wanted to be a reliable witness – that was why he had stayed alive. He couldn’t let them confuse him. He couldn’t think about the men who sat behind him, haunting his every word. He couldn’t imagine their eyes, their smiling faces. The effort was inhuman. Kaduk put on a show: he paraded into the courtroom with his hands stiff at his sides and his head thrown back proudly. He ridiculed the court, the witnesses, and even the men next to him in the dock who couldn’t remember anything. Klehr laughed and spoke just as he had back then. Selection was called “making the rounds,” and killing with the disinfectant Phenol was called “inoculation.” He said what he thought: the method was costeffective, odorless, easy to use, and completely dependable. He found the judges obtuse. Why fuss? A quick death is humane! The syringe was hardly empty before the man was dead, he explained. Murder? Your Honor, sick ain’t the word for those people. In plain German: They weren’t ill, they were half dead.

Heiner made it through his second testimony, barely stuttered, and did not let them confuse him. He did not break down. He was proud of himself, but only made peace with his performance later, after he had written down what he actually wanted to say. Whenever he was asked, even years later, he could recite the text like a ballad.

Your Honor!

I worked as a typist in Block 21, the prisoner’s infirmary. That’s where I learned to use a typewriter, practically overnight, otherwise I wouldn’t be standing here.

The typing room is on the ground floor of Block 21, just on the left as you come in. Sixteen men type constantly, day and night. We have quotas. We type death records. The first shift runs from six in the morning until six at night and the second begins at six at night and ends at six in the morning. Death records, you have to understand, are written only for people who have numbers – those are the ones actually admitted to the camps – most people on each transport don’t even make it that far. No records have to be written for people who are to be killed immediately. Several times a day an SS man brings us a list with names and numbers of the dead. We don’t know how these people died. We can choose from thirty different illnesses. According to my typewriter people die of heart failure, phlegmons, pneumonia, spotted fever and typhus, embolisms, influenza, circulatory collapse, stroke, cirrhosis of the liver, scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough, and kidney failure. Under no circumstances is anyone tortured, beaten to death, or shot at Auschwitz. No one starves, dies of thirst; no one is hanged, no one gassed. We write death notices twenty-four hours a day – eight hundred to a thousand every shift – and we write doctor’s reports for the relatives, but it’s all an empty clattering of keys.

Here Heiner paced his speech as if chanting a hasty Our Father. You could see him typing: Prisoner 128 439, Otto Schnur, born 24.9.1905, previously residing in Hannover, admitted to Auschwitz Concentration Camp on 19.10.1942. Period. On 28.11.1942 Prisoner 128 439, Otto Schnur, was admitted to the camp infirmary. Period. A clinical and radiological examination found typhus, which resulted in cardiac failure, and he collapsed and died on 2.12.1942 at 19:35. Period. If the deceased was a citizen of the German Reich, a copy of the report was sent to the relatives. I don’t know what Prisoner Otto Schnur actually died of.

Your Honor!

Do you know what phlegmons are? Phlegmons are inflammations of cellular tissue, primarily in the legs, as a result of hunger and filth. The legs swell – they get thick like Doric columns and the feet start to look like cannonballs. The skin cracks and pus is secreted through the cavities. And – here he holds his nose – it smells rotten and sweet…you can’t imagine the stink! Sometimes I smell it in my dreams, and I get sick and have to vomit. Otherwise, I must say, the work was perfectly pleasant. Except that sometimes it broke your heart. You come across the number of someone you saw in the morning and now it’s afternoon and he’s dead. What happened to him? Was he shot? Did he get his head bashed in? When it’s for someone you know, when you have to invent a cause of death for a friend – that’s a terrible thing.

Your Honor!

The death-ledgers from the infirmary in the main camp survived; 130 000 numbers from the summer of ’42 to the summer of ’44. It’s hard to fathom what human beings can get used to. We ate our bread next to half-decayed people. We chatted. Sometimes we made jokes and laughed.

Now, for Klehr. It’s as if I saw him every day. When Klehr made his selection, the prisoners had to leave the infirmary naked and stand in the corridor, each holding his medical card. The cards were laid on the table before Klehr. He smoked a pipe and singled out sick prisoners with its stem: Step forward! You and you and you and you. Klehr picks up the first card. He has time. He looks at the card. The entries reveal how long the person who stands naked before him has been in the infirmary. He puffs on the pipe. Fourteen days! He puts the card aside, picks up the next one, shakes his head. Just two days in the infirmary and already a Muselman! He sets the card aside. No one has ever survived more than fourteen days in the infirmary. During every selection one of us typists sat out in the corridor. Klehr announced the numbers and we wrote them down. These were the numbers of people he had chosen to die. The people were still alive while we were pecking out their death records. Dead of heart attack, dead of phlegmons, pneumonia, kidney failure, spotted fever, typhus, embolism, influenza, circulatory collapse…Everyone whose cards we had sorted out was picked up and brought to Klehr in Block 20.

Your Honor, in Block 20, Klehr injected Phenol into the hearts of the people he’d selected. He killed them in the “dressing room” – the room behind the curtain. There was a small table with the needle and the Phenol. Next to it was a chair where the victim was forced to sit. Most of them were so weak and their minds so worn down that they just let themselves be killed. But one time I was there when a man cried out and begged for his life and tried to protect his heart with both hands. Klehr ordered his assistants, who were prisoners too, to twist his arms so that the right arm lay against his back and the left could be pressed to his mouth. Then it was quiet. The area around his heart was free.

Once I had to deliver a message to Block 20. The curtain to the “dressing room” wasn’t closed. I saw Klehr with the needle in his hand. He looked into my eyes, annoyed, as if I had interrupted his breakfast. He lifted the needle and snarled at me. Beat it – or do you want a shot too?

We had this crazy fear of Klehr because he had no anger towards us. He killed with a light touch, without hatred.

Your Honor!

The perpetrators of these crimes weren’t sick in the head – they weren’t any crazier than you or me. If this playground of murder in Poland, if I may call it that, hadn’t existed, Klehr would have stayed a carpenter and Kaduk a nurse. Or a firefighter. Dirlewanger would have remained a lawyer, fat Jupp a dumb gangster, and Palitzsch, if he hadn’t died in the war, would have been Chief of Police or Secretary of State, and Boger would have been manager of the local insurance company. Or a teacher with a secret lust for punishing children. He wouldn’t have built the Boger swing. The perpetrators, Your Honor, were young and ambitious. They wanted to succeed at what they did. What it was didn’t matter. They acted like employees, hungry for praise and advancement. The sadists aren’t the most dangerous. The most dangerous are the normal people.

Your Honor, if you and I were to meet again in such a place, I would stand among the prisoners. You don’t know where you’d stand, I’m one step ahead of you there.

At this point Heiner paused to free himself from the sentences that could have driven him mad. End of the ballad.

Your Honor. You hear our stories. You record them. They touch your mind. They touch your intelligence. Perhaps even your imagination. But you’re not one inch closer to us than you were before the trial. Nothing in the world can bridge the gap between your imagination and our experiences.

[…]

As if the route were a one-way street, it was always Lena who traveled to Vienna, never Heiner to Frankfurt. My treasure, he wrote, going to your country and walking down the street is like entering a haunted house. I never know when a ghost or devil might jump out at me.

Dearest treasure, Lena replied, we bought two tickets to this haunted house – don’t forget that.

My treasure, Heiner wrote, it’s a stupid question, but I’m asking it anyway: How can you love someone like me?

Lena was more scrupulous with language than Heiner. I don’t love someone like you, I love you.

She put down her pen. Lena knew exactly why she’d fallen in love with the man who had collapsed before her very eyes. It wasn’t his weakness that attracted her; it was the defiance and pride in his pale face and the tone of his “Servus” when he opened his eyes. He had needed her help, but he hadn’t surrendered himself to her. His “Servus” was a combination of thanks and scorn. He let her help him, and watched her as she did so. He didn’t attempt to hide his curiosity about the woman who found him a chair and fed him chocolate. She loved him, she just didn’t know whether she would be able to tolerate a man who lived with a mustard jar that he wanted to be buried with. He would set it next to other peoples’ plates and with a hint of typical Viennese mockery in his voice, he’d ask: Look, what might this be? The same guessing game every time. South Pacific? Broken shells? Gravel? A short pause, a little smile, his gentle voice. ! They’re tiny bits of bone…How many times could one bear that?

He didn’t like to cook, but it didn’t bother her, since he set the table with such ceremony each time – as if the smallest snack was cause for celebration. He washed dishes as if it were a special treat, his cool hands warming in the hot water – but the way he ate! Meat, bread, eggs, vegetables – he chewed everything he put in his mouth into a mushy paste. He analyzed every fiber, tasted, wrung out, sucked the taste from every morsel until the paste in his mouth had become a dry ball that he divided into portions with his tongue before swallowing them. He ate to quiet the huge old hunger that could never be satisfied. She didn’t know if she could ever get used to such desperate exploitation of food.

In Vienna Lena learned to play Halma, a board game from his childhood collection. The rules were simple. Each player got fifteen little men, which he could place in one of six triangular areas. The goal was to reach the opposite triangle by shrewd jumps over your own and your opponent’s men. He called the triangles blocks and the men comrades. He always chose red men – his chevron in the camp had been red – and Lena could choose between black or green, since he’d gotten rid of the yellow ones.

Choose! Black or green?

Black chevrons were for the Asocials, the Asos, though no one knew exactly what the Nazi definition of Aso was. A homeless person, a person without a job, a thief, a beggar, a loafer, a prostitute – anything was possible. Green was for Berufsverbrecher – “professional criminals.” The Bv’s did the Nazis’ dirty work. Lena liked green better than black, but under these circumstances she chose the black comrades. Heiner had learned to play Halma from Kostek, a typist in the prisoners’ infirmary. Kostek had drawn a six-pointed star on a stolen scrap of paper. For playing pieces they used little stones they found on the camp road – light ones and dark ones. Two work groups, called Arbeitskommandos, were trying to cross the camp road and each used the other as a springboard. Heiner had a good eye for clever jumps. He liked the game because the opponent wasn’t eliminated, just outsmarted. He was dead serious about the game. Often the red comrades jumped far outside the boundaries of the game.

____________________________________________________________________

MONIKA HELD was born and grew up in postwar Hamburg. As a freelance journalist, her career has taken her all over the world. She has been awarded many prizes for her journalism and her political commitment, including Solidarnosc’s Medal Wdzięczności, the Elisabet Selbert Prize and the German Social Prize. She lives in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

ANNE POSTEN‘s translations and original work have appeared in n+1, Gigantic, Hanging Loose, Words Without Borders, FIELD, Stonecutter, The Free State Review, the University of Chicago Press, Frisch and Co., and Haus Publishing. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing and Literary Translation from Queens College, CUNY, and is currently living in Berlin as the recipient of a Fulbright Grant.