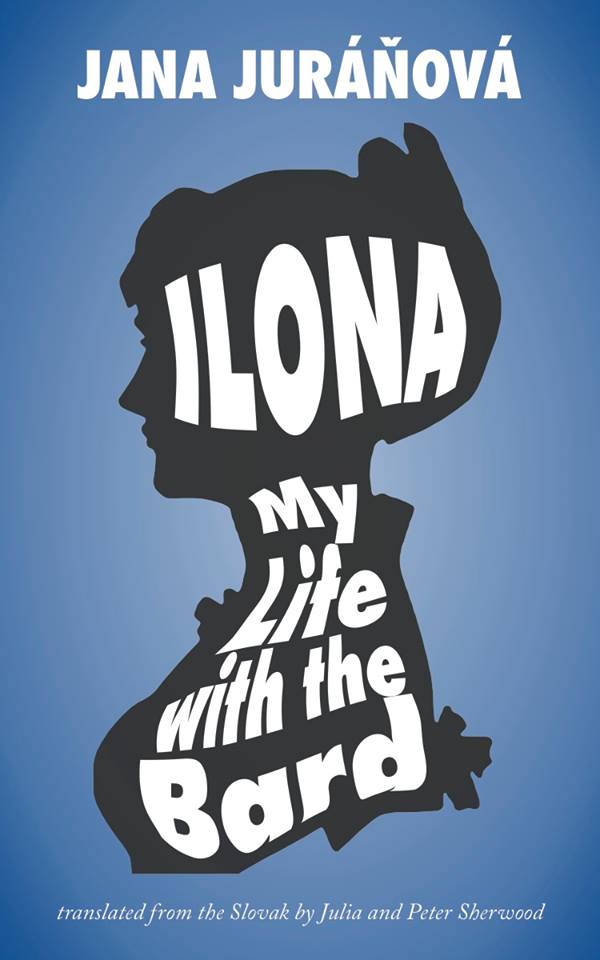

Ilona. My Life with the Bard

(an excerpt)

Ilona. My Life with the Bard

A novel by Jana Juráňová

Translated from the Slovak by Julia and Peter Sherwood

Published by Calypso Editions

Body and Soul

Spring was in the air. Tree branches were alive with the hope of future leaves. Everything glittered in a silvery mist. A gentle silvery glitter also played on Ilona’s hair, around her forehead and ears. Ever since discovering her first gray hairs she showed them off like a gem ready for more chiseling. She began to wear gray and blue to emphasize her new smart looks. Her dark eyes and full lips looked even more striking now they were framed in silver.

It was morning and Ilona was busy dusting as usual or perhaps she was watering the flowers. After a while, just out of curiosity, she looked out of the window as this was the day when the next visit by the professor from Prague was due. Nádaši had gone to meet him at the station and her husband was ready in his study, bow-tie and all. This was a very special guest indeed. She inhaled the balmy spring air. Today would be a glorious day. And so very interesting. Perhaps she, too, might get a chance to talk to the young professor.

She met him on the porch and he lavished praise on her flowers. They went inside. The house was all tidy, everything was in its place. Ilona took some coffee and two glasses of wine into the study. Her husband opened a box of cigars, lighting one for himself. Cigars, he said – as he always did – were his dearest friends, especially Cuban ones. And the guest, the professor from Prague, perhaps trying to ingratiate himself, said that Vrchlický, too, smoked cigars while working. He also remarked on the symbolic meaning of the busts the two poets kept on their desks. Vrchlický’s desk had a bust of Dante; Hviezdoslav’s one of Shakespeare. Ilona’s husband then explained at great length how obliged he felt to Vrchlický for his translations of world literature into Czech which, he said, had brought a touch of Europe, indeed of the wide world, into his provincial loneliness. Puffing on his cigar, he declared himself to be the Czech poet’s disciple. Then the visitor recounted, also at considerable length, how Balzac used to smoke while working and how indeed many famous writers would not have managed without tobacco. Ilona’s husband was visibly pleased to hear that. His face brightened up, his eyes acquired an even kindlier glow. Ilona imagined all those famous men sitting somewhere on Parnassus smoking, first in silence, then perhaps discussing their work for a while, each flanked by his own bust.

She went to the kitchen to prepare a snack. In the quiet of the kitchen she tried to imagine what Vrchlický’s study might have looked like when he was still living with Lída. Was she the one who gave him the bust of Dante? Had she and her best friend from the Senior Girls’ School been thinking alike? How happy her husband’s praise had made her when she presented him with Shakespeare’s bust during their first Christmas together. He had kept it on his desk ever since and took every opportunity to mention that it was a gift from her. He also keeps a portrait of her, from her younger days, above his desk. When her husband is away, taking the waters or traveling, Ilona makes sure to dust the portrait.

She won’t join them in his study now. He and the professor will discuss his work in great detail. Then they will discuss his future plans, eventually moving on to politics. If they don’t finish by lunchtime, they will continue after lunch. Ilona might not get a word in edgeways and even if she does, it will be only to ask the visitor to help himself to one thing or another. If an opportunity to say something doesn’t arise, she won’t insist on talking. Silence is golden sometimes. Now she has to keep an eye on Kata in the kitchen to make sure she doesn’t make a mess of things. Then she and Sidka will lay the table. And she will get the pastries ready to be served with the afternoon coffee.

What a pleasant day it is today. It was chilly in the morning but now the mist has lifted and it has gotten warmer. This day feels full of hope and promise for no special reason. It’s probably just the early spring beguiling the senses. Ilona is happy to be beguiled. It is so pleasant. A long time ago, when she was still a student in Prague, early spring used to fill her mornings with this kind of hope and promise. This morning has brought back memories of her youth. It was a time when she wondered what her life might bring and looked forward to the future. Even today she can recall her anticipation, her excitement as a young girl. But it is only a state of mind, pleasant though deceptive, a state of mind evoking a time when she had looked forward to the life she was living now. It will be helpful to feel that way today. It will help her to get through this day and perhaps some other days as well. Oh, the lovely spring days in bracing cool Orava! After all, Prague was not all that warm in springtime either. But back then she didn’t care. Her whole life was still ahead of her, and a beautiful and happy life it was going to be. She was looking forward to visiting beautiful cities with her husband one day and seeing the seaside. The seaside was something she particularly looked forward to. But her husband doesn’t travel anywhere except to take the waters and even then he travels alone or with her father. And on those occasions when he did set out on longer journeys he went without her. After twenty years of living together they moved from Námestovo to Kubín and have stayed there ever since, like two boulders. So geography, once her favourite school subject in Prague, turned out to be the least useful in her future life. Distant countries, seas, great cities – for her they remained confined to maps. And later, when he wrote to her from his journeys, she could only imagine it all.

When her husband decided to go to the seaside she hoped she might accompany him. She wanted to see foreign countries with him, she wanted to see famous paintings in famous galleries with her own eyes. But he chose to travel without her, taking her brother instead. When the protestant church in Dolný Kubín burnt down in 1893, Ilona’s brother went to Germany to collect money for a new one. He invited his brother-in-law to come along. She wanted to join them. But they would not let her.

During the preparations for the trip she kept raising the subject with her husband, trying to persuade him, hoping he might yet change his mind. But he was adamant. Sometimes he did not even respond to her. She went so far as to bring up the subject in the company of strangers but it was no use.

Once, when they had visitors, he asked her suddenly: “Tell me, my dear wife, what should a good husband and wife be like?”

“One body and soul,” she was quick to respond.

“You see. And when I go to the seaside it’s as if you were there with me.”

The company laughed appreciatively at his wit. She couldn’t contradict him. Had they been alone she would certainly have come up with a sharp retort. She wanted to say something after the visitors left. But he locked himself in his study because he needed his peace and quiet. And then he glossed over the whole thing. It was all very civil, well-mannered, as befits a good couple.

And so her husband and her brother traveled through Germany, went to the seaside and visited various countries. Their journey began in Vienna.

Mme Ilona Országh

Námesztó, Ungarn,

Comitat Árva*

My dearest Ilonka! We are in Vienna feeling well after an auspicious journey. I am writing this in St. Stephen’s Cathedral. Tomorrow I will go to see the sights. What about yourselves? I trust you are all well. Farewell, my dearest, I send you many kisses and my sincere greetings to everyone.

In Vienna, July 9, 1895

Yours, Pavol

They continued their journey via Salzburg:

July 12

…. We have reached Salzburg. We feel excellent… This afternoon we shall continue towards Munich.

He was particularly impressed with the local picture gallery.

July 13 and 14

My dearest wife!… It was well past eleven o’clock by the time we reached Munich and we shall pass some three days here. First of all we sought out the main post office where I was delighted to find your first poste restante letter and to learn that you are all in good health. Be sure to direct your next message to Stuttgart, also poste restante at the main post office…. I have seen and experienced much that is of interest. Munich is a beautiful city. Embracing you and kissing you in spirit,

Yours, Pavol

July 14

Dearest Ilonka!…. We are keeping well. We have seen many, many beautiful things here in Munich. From now on please make sure you direct your messages only to Hamburg, poste restante…. May the Lord look after you….

From Munich they went on to Ulm, then to Cologne, Bremen and Hamburg. They stopped in Berlin and Wittenberg and, naturally, didn’t leave out Dresden either.

July 16

My dearest Ilonka! We have left the delightful city of Munich and have arrived in ancient Ulm. We have just visited its magnificent cathedral…

July 17

Ilonka, dearest!

Stuttgart is a beautiful city but not quite as beautiful as Munich. I went to the main post office yesterday as well as today but found no messages from you…. How are you? I hope nothing bad has happened? We have been keeping well so far. Although, truth be told, everything is very expensive here… German cuisine is very poor indeed, I have only had soup twice and have subsisted solely on roast beef, like some wild beast! Farewell, my dearest….

His letters recounted the things he had seen and experienced, and described his feelings. Who else was he to share all this with if not his wife? After all, she would have liked to accompany him, it just didn’t work out. So he did his best to make her happy by sharing the impressions from his trips so that she could picture everything just as if she had been there by his side. She was happy to receive his letters and postcards, conjuring up in her mind everything he described and comforting herself with the thought that he was seeing all those things on her behalf, too. She followed his journey in her imagination, feeling ever so slightly sorry for herself. But what is the point of rebelling against fate?

She has kept all his postcards. She has treasured them. The beautiful pictures, the sincere words. He had shared all this beauty with her. He was able to do that because her upbringing, her education and her willingness enabled her to be always there for him so that he could always lean on her, the frailer sex. And she, in turn, could lean on him. It was mutual, as befits a married couple. She provided the beneficial shade, making sure all the while not to block his view, to support him only when necessary. Who knows, maybe they would have quarreled if she had traveled with him. Who knows if she would have seen things the way he saw them. But she has never traveled and all she could do was see all the wondrous things through his eyes. That is how she talked of them and remembered them. She always saw herself by his side, reading his impressions and taking pleasure in them.

Eventually she got over the pain of having been left behind. After all, so much else had happened to remove the slight shadow this had cast over their relationship, a shadow he was never even aware of. And what use would it have been to dwell on that shadow? She knew that his travels had a noble purpose. Perhaps it really was not appropriate for her to accompany him.

Only much later, when he developed the neck ailment, did she go along with him to a medical examination in Vienna so that a laryngologist could check for a suspected malignant tumor. Luckily, that was immediately ruled out, the first examination showing it was nothing serious, just a narrowing of the connecting tissue. And so, all of a sudden, there they were on a trip to Vienna, one of the few she had made with him. They saw many museums, exhibitions, churches, went to the opera and on their last day they went to inspect the great marble plaque where in golden letters were engraved the names of the most famous professors at the University of Vienna, including Ján Kollár** . At this, Ilona’s husband gave a little sigh: “What a tiny little nation we are, how poor compared with all this Viennese opulence.”

* While Slovakia was part of the Kingdom of Hungary, the postal services used Hungarian versions of Slovak place names. Námesztó is Hungarian for Námestovo; Árva is the Hungarian for Orava.

**Ján Kollár (1793-1852) was a Slovak-born writer, archeologist, politician and leading proponent of Pan-Slavism. He wrote in Czech.

____________________________________________________________________

JANA JURÁŇOVÁ is an acclaimed Slovak writer, playwright, essayist, translator and publisher, co-founder and editor of the feminist educational and publishing project ASPEKT. She lives in Bratislava. She has written several theatre and radio plays, children’s stories and short stories. Her latest collection of short stories is Heavenly Loves (2010); her longer fiction includes the feminist crime story The Suffering of the Old Tomcat; Beadswomen (2006) and Ilona. My Life with the Bard (2008). Her three most recent works of fiction have been shortlisted for Slovakia’s most prestigious literary prize, the Anasoft Litera Award, and several of Juráňová’s short stories have appeared in German, English, Hungarian, Polish, Czech, and Norwegian translations. In 2012 she published the memoir of the prominent journalist and translator, Agneša Kalinová, My 7 Lives , in the form of a book-length interview, and her latest work of fiction, the novella Unfinished Business appeared in 2013. Jana Juráňová’s translations from English include Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas and Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble as well as books by Margaret Atwood and Jeanette Winterson.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translators:

JULIA SHERWOOD was born and grew up in Bratislava, which was then Czechoslovakia. After working for Amnesty International in London for over 20 years, she became a freelance translator in 2008. Her book-length translations include Samko Tále’s Cemetery Book by Daniela Kapitáňová, Freshta by Petra Procházková, Hubert Klimko-Dobrzaniecki’s Lullaby for a Hanged Man (from the Polish) and, jointly with Peter Sherwood, Peter Krištúfek’s The House of the Deaf Man. She has also translated work by writers such as Uršuľa Kovalyk, Balla, Michal Hvorecký and Leopold Lahola among many others.

PETER SHERWOOD taught at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (now part of University College London) until 2007. From 2008 until 2014 he was the first László Birinyi, Sr., Distinguished Professor of Hungarian Language and Culture in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has translated the novels The Book of Fathers by Miklós Vámos and The Finno-Ugrian Vampire by Noémi Szécsi as well as stories by Dezső Kosztolányi, Zsigmond Móricz and others, along with works of poetry, drama and philosophy.