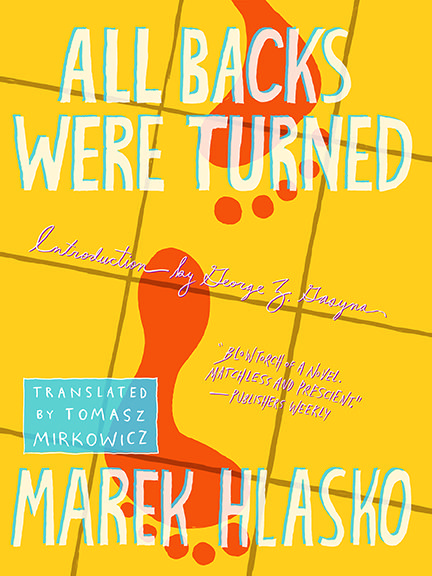

ALL BACKS WERE TURNED

(an excerpt)

All Backs Were Turned

A novel by Marek Hlasko

Translated from the Polish by Tomasz Mirkowicz

New Vessel Press

140 pgs.

They were sitting in a small restaurant by the sea; they had just finished eating. Israel turned to Dov.

“Do you think I can manage?” he asked.

“Sure you can,” Dov said. “Many guys work there and they manage okay.”

“You said before that maybe I wouldn’t.”

“No,” Dov said wearily, “I didn’t say that. You should know how it is with a new job. In the beginning it tires you out, then you get used to it, and then you stop enjoying it. It’s almost always like that.” He stopped a passing waiter. “Bring me a glass of brandy,” he said.

“Don’t drink brandy, Dov,” Israel said. “Better have some coffee. It’ll make you feel better.”

“I don’t want to feel better,” Dov said. “I want a shot of brandy, that’s what.”

“Will he come?” Israel asked. “I’m beginning to worry.”

“No need to,” Dov said. “He’ll come. Look at those girls and stop worrying.” He pointed at two girls drinking coffee at the next table and held his hand in the air until one of them turned her head in his direction. “Just look at them.”

“What do you want?” the girl asked.

“You can turn around again,” Dov told her, letting his hand drop. “One more disappointment,” he said, looking her straight in the eye.

A stout man in a khaki shirt walked into the restaurant. He stopped in the middle of the room and stood there, holding a pair of sunglasses in his hand. Sweat trickled down his face. Finally he saw the two men and began making his way toward them, never once apologizing to the guests he squeezed past, jostling their tables with his strong, heavy body. The chair he lowered himself into creaked loudly under his weight.

“Sorry you had to wait for me,” he said. “It took me half an hour to find a parking space.”

“It’s okay,” Israel said. “The important thing is that you came. We haven’t been waiting long.”

The stout man didn’t look at him.

“When do you want to start work, Dov?” he asked.

“Tomorrow.” Dov finished off his warm brandy and placed the glass gently on the table.

“Do you know what the pay is?” the stout man asked.

“No,” Dov said. “But I know you. It can’t be good.”

“Whatever it is, it’s fine with us,” Israel said, but the stout man didn’t look at him this time either. His gaze was fixed on Dov’s face and the joined eyebrows.

“Dov,” he said, “you had ten years to find yourself a good job and settle down. Why didn’t you? Lots of people were ready to help you.”

“When can we start?” Dov asked.

The man didn’t say anything for a moment. Then he said, “You, Dov, can start tomorrow.”

“That’s not what I asked. When can the two of us start?”

“Dov, this is not a job for him. I never told you I’d have work for both of you. I said I’d have work for you. And only because it’s you.”

“You’re wasting your time,” Dov said. “We’ll find something else. You have a garden by your house, don’t you? So go home and water your flowers.” When the stout man didn’t answer, after a while Dov said again, “You’re wasting your time sitting here.”

“Why do you insist on towing him along, Dov? He’s not your girlfriend. And he can’t work at the jobs you can. You should know that.”

“Yeah,” Dov said. “Like I said, you’re wasting your time. Just get up and leave, okay? You haven’t ordered anything, so there’s no reason for you to stick around. They won’t bill you just for sitting down.”

“You’re like a pretty girl, Dov,” the other man said slowly. “Whenever two girls are inseparable friends, one is pretty and the other so ugly it makes your eyes hurt. You insist on taking this guy along wherever you go, even though you couldn’t find a less likely man to team up with in the whole world.”

“Gimme a chance,” Israel said. “Believe me, I’m strong.” He leaned toward the stout man. “Ask Dov. Yesterday we had a fight with some men in a bar. Ask him how I managed.” He touched the stout man’s shoulder, but the man shook off his hand and turned to Dov.

“Strong men always think they can do something for the weak. And wise men think they can improve the minds of fools. It never works. In the end strong men go down because of weaklings and wise men go mad because of fools. It’s always been like that. How come you decided to ask me for help?”

“I’ll tell you,” Dov said. “I came to you because I was sure all honest and respectable men would turn me down. The way you did. And I know you well and know you’re a scoundrel.”

They looked at each other and suddenly the stout man burst out laughing.

“Hey, lover boy!” he shouted at the waiter. “Get us a bottle of brandy.” He gave the waiter a shove with his heavy hand sending him halfway across the room. Then he turned to Dov. “Mark my words. There were once two wise guys in this world; one was named David and the other Goliath.”

“Right,” Dov said. “I’ll remember that.” He was looking straight ahead, at the sea, where the first lights were beginning to blink, then he turned his head to the left and looked toward the lights of Jaffa. “But it’s better to be Goliath and die from a stone than to be David who became king, but was the cause of many tears.”

“You said that, Dov, I didn’t,” the stout man said. He picked up a glass and held it in his hand. “You have a brother in Eilat, don’t you?”

“Yeah. Why?”

“When you were in court today, the judge must have told you that if you got into any more trouble, they’d lock you in the slammer for quite a while. Look, I know you; you just can’t keep your nose clean. Tel Aviv is bigger than Eilat; if anything happens here again, the judge will forget about your heroic past—”

“Skip that stuff,” Dov said.

“Well, go to Eilat. That place is full of guys like you. You can do whatever you like and nobody will bother you. If you slug someone, the guy won’t start yelling for the cops, only slug you back. I’ll give you my jeep; you can pay me later. In Eilat you’ll look up this guy I know working at the airport and he’ll help you find tourists you can drive out to the desert, show them around. Tourists like taking pictures and bouncing their guts in jeeps; it makes them feel like adventurers. And you’ll be making enough for a man to live on.” He poured himself a shot of brandy.

“Sorry. Enough for two men to live on. When winter comes, you’ll come back here and pay me my share.”

“All right,” Dov said, getting up. “I’ll call our hotel and find out what time we have to check out. I want to leave tonight.”

Women turned their heads to stare at him as he walked across the room, but he didn’t notice the looks they sent him. He resembled a man walking across a cornfield and parting the stalks with his hands.

“Funny, isn’t it?” the stout man turned to Israel. “The way a woman can hurt a man.”

“Yeah,” Israel said.

“When did he see her last?”

“A year ago,” Israel said. “Maybe more.”

“And he still thinks about her?”

“I guess so.”

“She really got to him,” the stout man said. “He’s like a blind man now. Why did they split? Did he ever tell you?”

“No. He never talks about it. Not even to me.”

“Tell him to stop thinking about her. There are plenty of other women around, thank God. Tell him I said that.”

“Tell him yourself,” Israel said. “Why wouldn’t you give me a job?”

The stout man looked at Israel for the first time since he’d walked into the restaurant. He placed his glass on the table and said, “You should go away. You aren’t suited for this country and you don’t like it. Dov loves it. Too bad he’ll come to such a stupid end.” He gazed into the distance; his eyes were red and tired. “When I came to Israel, the man who worked in a kibbutz drying swamps, building roads, or planting orange groves was considered the number one hero. Now it’s the rich American Jew who comes here to invest his money and won’t even bother to learn ten words of Hebrew. So I, too, decided to start making money. Why not? I don’t like to appear a fool. I’m telling you to go away. Take my advice, sonny boy.”

“I’ll get used to it,” Israel said.

“Yeah, you might get used to this country. But you won’t learn to like it.”

Dov came back and sat down. It was dark now and a huge moon was hanging low over the sea, but the beach was still crowded and the heads of swimmers dotted the broad white waves far away from land.

“We might as well stay the night,” Dov said. “They charge you anyway if you check out after six.” He turned to the stout man. “Where’s your jeep?”

“Outside. I came in it. I knew I had to give you this last chance. Even though you’ll let it slip through your hands, you dumb bastard.” They watched his swarthy, meaty face and his thick fingers playing with the glass.

“What does your dad do, Dov?”

“He lives with my brother.”

“And how is he? Has he changed a lot?”

“He’s eighty now. You don’t change at that age.” Dov rose, taking the jeep’s registration card and the car keys from the stout man, but he didn’t walk away yet. For a moment he stood there, not looking at the sitting man, and finally said, “Give me an advance. I need money for gas. I’ll pay you when I come back for the winter.”

“Don’t you want my dentures too, Dov?” the stout man asked, but he reached into his pocket.

A while later he watched the two men cross the street and climb into the jeep, and for the first time he noticed how much they resembled each other. “This is how it had to be,” he said aloud to himself. “That’s why I came here. To give him my jeep and my money, knowing he’ll waste it all.”

“Will you pay the bill, sir?” the waiter asked.

The stout man turned to him. “Why do you bother to ask? Has the big guy who was here ever paid you?”

“There was a time when he settled his bills,” the waiter said, adjusting his dirty cummerbund. He had a huge nose and a thin, tragic face. “She brought him down.”

“Yes,” the stout man said. “She did.”

____________________________________________________________________

MAREK HŁASKO, born in 1934, was a representative of the first generation to come of age after World War II, and was known for his brutal prose style and his unflinching eye toward his surroundings. He was known as the Polish James Dean, and made his literary debut in 1956 with a short story collection. In 1956, Hlasko went to France; while there, he fell out of favor with the Polish communist authorities, and was given a choice of returning home and renouncing some of his work, or staying abroad forever. He chose the latter, and spent the next decade living and writing in many countries, from France to West Germany to the United States to Israel. Hłasko died in 1969 of a fatal mixture of alcohol and sleeping pills in Wiesbaden, West Germany, preparing for another sojourn in Israel. Besides Killing the Second Dog, his translated works include the novels Eighth Day of the Week, All Backs Were Turned, Next Stop – Paradise, and The Graveyard, as well as a memoir, Beautiful Twentysomethings.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

TOMASZ MIRKOWICZ was born in Warsaw in 1953. He translated the works of Ken Kesey, George Orwell, Jerzy Kosinski, Harry Matthews, Robert Coover, Alan Sillitoe and Charles Bukowski into Polish. He was also a fiction writer and critic. As a child he spent four years in Egypt; in his adult life, he returned there four times and traveled the world, trying to see as much as he could. He was educated at the Institute of English, in Warsaw, where he later taught American literature. Mirkowicz was the recipient of the Literatura na Świecie Award for Best Prose Translation of 1987; the Polish Translators’ Association Award for Best Prose Translation of 1988 and FA-art Short Story contest winner (1994). Tomasz Mirkowicz died of cancer in 2003. In addition to translating All Backs Were Turned, he also translated Hlasko’s novel Killing the Second Dog.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Marek Hłasko:

A Short story in Tablet

Essay on Hłasko in Los Angeles Review of Books

Review of Killing the Second Dog in Asymptote