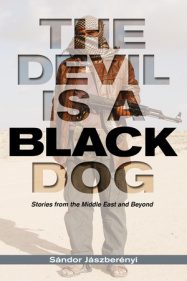

The Devil is a Black Dog

A novel by Sándor Jászberényi

Translated from the Hungarian by M. Henderson Ellis

New Europe Books

208 pgs.

It’s about as bleak a situation as you can imagine getting into, struck down with malaria in the Sudanese desert, twelve hours from the nearest pharmacy, lying helpless in a mud hut with neither prayer nor magic slowing death’s approach. Then, a moment comes when the Hungarian narrator’s feverish mind conjures up his father out of thin air and they have a poignant but all too typical father-son exchange:

“This is what you wanted, right? Do you at least know what you’re looking for here?” he asks.

“I’m a correspondent. It’s my job to go to places like this.”

I smile, because I know this is not the whole truth, but I won’t tell that to my father, especially if he happens to be the product of a fever-induced dream.

Reading on past this opening story in Sándor Jászberényi’s stunning debut short story collection The Devil is a Black Dog one might find that “the whole truth” continues to remain somewhat elusive. Yet as we follow it from that remote desert on to Gaza, Libya and Tahir Square it becomes possible to at least discern the shape of this truth, and as we pursue its traces further in Yemen, Chad as well as the deceptive calm of provincial Hungary, we can see that what drives this correspondent to these immensely dangerous places really isn’t primarily his work but, paradoxically, his survival.

For this correspondent, sometimes unnamed and other times referred to as Daniel Marosh, this perilous region has allowed him to find a horrifying purity of life, where all the bullshit and trivia of everyday existence is sifted away, not by spiritual effort, love or asceticism but by Muslim militia groups, disease, a steady flow of guns, fanaticism and the stifling desert heat:

It was only there, indeed, in the middle of a war, that Marosh really felt free. The world simplified to “yes” and “no”, to life and death. He liked how it clarified things, that there were no loans or credit, no competitors with better family backgrounds or better dispositions, that there were no chosen ones, and that everything was for the last time.

Jászberényi doesn’t glorify war and violence by any means. He is able to express their horrors in ways that, depending on the story, provokes outrage, heartbreak, cynicism and fear, all the while showing that there is a price to pay for this freedom that Marosh and his compatriots achieve, with death and disease being just two of the more obvious items on the price list.

The stories are a pitiless litany of death and betrayal. The deaths range from the chillingly observed, such as in “Registration”, when two Europeans working in Africa debate the differences between their circumcised and uncircumcised penises as they go to register the murdered bodies in a mass grave, to the mystical, as in “The Blake Precept”, where a soldier’s visit to a fortune-telling ghost rider in Chad leads to a chilling conclusion. Then, in “The Majestic Clouds” Jászberényi achieves an unexpected tenderness in the usually guarded Marosh’s affection for a twelve-year old Sudanese girl who is forced to undergo female circumcision, with tragic results.

The betrayals are also brilliantly portrayed and dig far below the surface. A story of a smug westerner talking the talk of humanitarianism at a refugee camp shortly before abandoning its occupants to be massacred is followed by one of the journalist narrator returning from Budapest to his hometown following the death of his father, totally indifferent to his loss and occupied only with getting rid of his late parents’ faithful dachshund. Making this betrayal seem colder than the mass killing that preceeded it is a literary tour-de force. If Marosh seems like a moral compass in navigating some of the evil he witnesses in his work, Jászberényi uses the few stories set in Hungary to tear the needle off the compass and leave the reader without any illusions. No one gets off scot-free in this book.

In the opening story, “The Fever”, the narrator tries to answer his hallucinated father’s question as to why he came to these dangerous places. The response that arises from his feverish brain really isn’t all that different from the long literary tradition of the westerner coming to Asia or Africa in search of truth and spiritual clarity, except that these are far more dangerous times and he has come to their most dangerous places, finding a kind of Zen at the barrel of a Kalashnikov:

… I never wanted to live a sensible life. I didn’t want to be a model citizen; I desired neither a family nor children, and when I found myself in possession of both, the enterprise wound up a dismal failure. I have answers only when the circumstances are clear, like life and death; that’s when I feel best, when the questions are easy, uncomplicated by the reflexes of a dying civilization.

–Michael Stein