THE DEVIL IS A BLACK DOG

The moon rose high above the town, illuminating the clouds, the apartment buildings, and the hills beyond in a red glow. The air was cool, like it was every evening in the hills. There was no electricity in the town, just the blood-colored moonlight that gathered at end of the alleyways.

“It’s like this from the storm,” said Abdelkarim, when he noticed my expression of awe. “There was a storm in the desert, and the moon looks red from the dust.”

He took a long drag from his cigarette. We had been coming out onto the roof most evenings since I’d moved into the mosque. It was good to sit in the night air, smoke hash, and talk about this and that. The government army had ended its shelling a few days ago. It was quiet now. Just the moon shone on the town, lighting up the destruction.

“Tomorrow the weather will be good,” said the imam.

“How do you know?”

“My wife heard it on the radio.”

I smiled and reached for the cigarette. Abdelkarim was in his early forties, but his beard was already gray. I had been staying with him for two weeks, since the day the Hotel Mecca was hit. The government had shelled the town indiscriminately, blowing the hotel to bits. When I’d come down from the hills, where I’d been staying with the Huthis, I found the building in ruins. The wretched hotelier informed me that he couldn’t return my two hundred dollars, because he needed it to feed his family. With no better idea, I knocked at the mosque where Abdelkarim was the imam. A big-hearted, generous man, he offered me a room. We immediately took to each other.

“What do you think? When will the foreigners return?” he asked.

“I don’t know. Another week, maybe.”

In truth, I had no idea.

The mujahideen controlled the roads, and kidnappings were common. My safest route back to the capital would have been to go with the armed convoys of the humanitarian organizations, but the soldiers had already evacuated everybody. I’d stayed behind, alone.

“There were many dead,” said Abdelkarim. It was also his job to organize provisions for the wounded. He wasn’t a doctor, but he could take their pain away; the town was awash with soggy, raw opium, brought from Afghanistan by returning mujahideen. The opium relieved the pain and induced good dreams. The mortally wounded could sleep until their hearts gave out. This was a merciful death for those who had been torn to shreds by gunfire, burned beyond recognition, or had taken a bullet to the stomach.

The wind caught Abdelkarim’s robe as he stood up and reached out for the banister.

“Tomorrow the weather will be good,” he said.

“Let’s hope so,” I said.

“I should take the girls out to kick a ball around. War shouldn’t be their only memory of their childhood.”

“Yes, that will make them happy.”

He had two girls, one three years old, and other five. I frequently ran into them around the house. Abdelkarim allowed me to listen in as he read to them from the Koran and then explained the meaning of the passages. It was the wife whom I wasn’t allowed to meet. That my meals were prepared and my clothing washed was the only indication that she lived in the house. Abdelkarim begged my forgiveness that he could not introduce me to her. A woman was not allowed to be in a room with a man who was not her husband or relative. Because of this, it was the custom in Yemen for new mothers to nurse their male infants together. They would sit in a circle and pass the baby from one to the next, allowing it to feed from each of their bodies, so they could all claim him as a relative.

“Let’s go to sleep, friend. Perhaps tomorrow we can get a hold of a Saudi television channel and watch the soccer match.”

“Inshallah.”

“I’ll fix the antenna.”

I tipped back the remainder of the karkadé that we were drinking. Bitter and cold, it stung the roof of my mouth. I took the pitcher in my hand and carefully, so as not to slip on the adobe stairs, started down. Abdelkarim followed, holding a gas lamp. Our shadows fluttered against the wall in front of us.

We arrived at the room where I slept, the floor covered in prayer rugs and horse blankets. There was no window, so there was no breeze, like there was on the top floor. By dawn, though, the room would be cold enough to see my own breath.

“Good night, friend,” said Abdelkarim. “I will wake you in the morning.” He shook my hand, then turned and began toward the floor below, where he lived with his wife. It was at this time that we heard a clamor coming from outside. Somebody was pounding against the mosque’s green iron gate. We both rushed to the building’s entrance.

Abdelkarim threw open the iron bolt and opened the gate wide. On the street stood a ten-year-old boy, barefoot and dressed in grimy clothing. From his belt hung an old Luger. His upper lip was quivering. He tapped his foot nervously. His eyes twitched.

“Thank you for opening the gate,” he said.

“What brings you here, Abdul Muhyee” asked my host. “And where is your clan?”

“The devil has come to the hills,” said the boy.

That was the first time I heard about the black dog.

Abdelkarim lit a gas lantern on the wall of the prayer room, the light revealing a green prayer carpet. Abdul Muhyee sat against the wall and gulped water from a goatskin sack. The liquid dribbled down his chin and gathered in dark stains on his robe. He drank deep and long as we waited for him to continue his story.

“I was putting the goats out to graze by the cave tomb as usual,” said the boy once he was ready.

“I heard movement coming from inside. I thought somebody from the town had come to dig up a body, so I went in. The cave was dark, and at first I couldn’t see a thing. . . .” His voice became clenched and he began to shiver.

“And what did you see, Abdul Muhyee?” asked my host.

“Bismillah, the devil! The devil was in the tomb in the form of a dog. He was eating human flesh and drinking blood.” As he told the story, the boy’s face strained with fear, and he paused repeatedly to recite the Shahada.

“And why do you think it was the devil and not just some stray dog? You know they have been hunting in packs up in the hills since the war broke out.”

“His eyes glowed red.”

“That’s just how they look in the dark. I wonder why you didn’t try to chase it away.”

“But I did. I took my gun from my pocket and shot at him. I emptied the entire magazine at that demon, but he didn’t move a muscle.”

“And then?”

“It turned its head toward me. Abdelkarim, I have never seen such a sinister face in my life. It was like he was laughing. Like he was laughing at me. I began to run, I ran as fast as I could.”

“I still don’t understand why you think he was the devil,” said Abdelkarim.

“He followed me all the way to the town outskirts. He only turned back when I said a Shahada. The name of the prophet stopped him.”

Abdelkarim went silent and stroked his beard. Finally he said to the young goatherd, “You are exhausted, friend. It seems we are all tired. Tomorrow we will look for the solution to this thing. Sleep here in the mosque.”

Abdul Muhyee, still visibly spooked, took the imam’s suggestion. We all parted ways to sleep.

The next morning I found Abdelkarim downstairs in the mosque. Abdul Muhyee was nowhere in sight. I washed in the well, then went into the prayer room, where breakfast was waiting. Abdelkarim’s wife had baked bread, which was steaming in a basket. We ate it along with yogurt and cucumbers. I asked him about Abdul Muhyee.

“I sent the boy home,” said Abdelkarim, as he tore into the bread.

“The kid was scared to death.”

“I convinced him that his mind was playing tricks on him. The last thing we need are rumors about the devil. We’ve trouble enough.”

“How did you convince him?”

“I told him that it was obvious to me that he hadn’t seen the devil.”

“And that was enough?”

“No. I also gave him my rifle.”

“Why?”

“Because divine help was also needed. I thought I’d give him the gun and bless the ammunition. Now no more trouble will come of it.”

“You convinced him your rifle can stop the devil?”

“It can stop this one. Mausers are good guns.”

Abdelkarim poured us tea.

“Are you going to try to write an article today?” he asked.

“No. My laptop ran out of power.”

“I’ll plug in the generator.”

“Don’t waste the energy. Even if I write an article, I can’t send it. The network is down.”

“In that case, would you like to come with me to see the tomb in the hills? I need to get to the bottom of this before gossip starts. With two of us, it will go quicker.”

“Of course,” I answered, and went to wash my face. The water from the well was cold and left dark green stains on my shirt.

We traveled on Abdelkarim’s beat-up Triumph 21. The paint was worn on the body but the seats were comfortable, because the imam was careful to keep them well oiled. It was a good little motorcycle and more than fifty years old. As opposed to modern Chinese trash, this one could withstand the climate, the night’s frost and day’s heat. He kept it stored under rough horse-blankets in the courtyard; it was well maintained, and he beamed with obvious pride when it roared to life that morning.

Abdelkarim drove, his robe blowing into my face when it caught the wind. We glided along, past the red hills; the black openings of the small caves looking like the gaping mouths of corpses. Red dust carried by the wind stuck to our sweaty clothing, leaving rust-colored streaks.

For about half an hour we wound our way down the serpentine dirt road that led to the caves where the tomb was. Since the town graveyard had filled up, the Saada people began to bury their dead in the hills.

Abdelkarim slowed down and came to a halt. The opening of the cave Abdul Muhyee had spoken about was in a hill above the road. We got off the bike and began to climb.

“Do the dogs normally raid the dead?” I asked as we hiked up the incline.

“More and more often. There are a lot of stray dogs. They go after the town’s trash as well. But at the beginning of the war, there was simply nothing to eat in the town, so they came out to the hills to hunt. It seems they have also begun to mate with the jackals.”

“I didn’t think that was possible.”

“A jackal is a dog as well, though we can say the stray dogs are more dangerous.”

“Why?”

“Because jackals are still afraid of men, but dogs are not.”

“What did Abdelmuyi mean when he said the dog was drinking blood?”

“I believe it is just as he said. There is no natural water source, but where there are wells, there are also people. Any dog that dares to get near the drinking water is certain to be shot by the shepherds.”

“That’s why they drink blood?”

“That’s why.”

“So they don’t die from thirst?”

“Indeed. Blood is a kind of water.”

The cave’s entrance was almost seven feet high; we both fit through comfortably. As Abdelkarim went ahead, I saw his hand poised on his robe. Over one of our dinners together he told me that he had been a soldier, and I knew that unlike the city dwellers of the capital, the knife on his belt wasn’t for decoration. It wasn’t an especially ornamented dagger; the hilt of a red copper blade protruded from its simple leather sheath. The imam turned and took a gas lantern from the cave’s wall. He looked for matches in his pocket to light it with. The pungent smell of congealed blood filled the cave and mixed with that of the gas.

Sand grated under the soles of our shoes as we went. Deep in the cave, spaces had been dug into the walls. They’d lay the dead there, and let the hot, dry air take care of the rest. The only problem was the linen sewed around the bodies. Since the offensive broke out, no new material had arrived in the hills, so what was left they used sparingly.

“What exactly are we going to do here?” I asked.

“It’s certain that pieces of the bodies have been strewn about. We are going to put them back in the their rightful places.”

“Out of respect?”

“Yes. And I don’t want people to start gossiping. In this area they are terribly superstitious. All we need is talk flying around about the devil.”

The light from the gas lamp flickered against the wall as we traveled farther into the cave. Soon we could make out the contours of the chamber where the burial places had been dug. We found the first corpse on the ground before us, upended on its side. The linen, brown with dried blood, was torn half away. Abdelkarim got on his knees by the body and placed the lamp on the sand. I stepped closer. The man’s throat had been ripped open, his innards were missing, and his face was chewed to pieces. It was an ugly sight, one I didn’t want to look at for long.

At least there aren’t any flies, I thought and knelt down next to Abdelkarim. I’ve always had difficulty stomaching corpses that were swarming with vermin.

“It was really a big dog,” said the imam, pointing to the prints in the dirt by the body. They were as big as an adult fist. The animal must have been two hundred pounds at least. “It fed here. It fed on the flesh, and the rest was just for play.”

“What makes you think so?”

“There are lots of prints here. I bet if you look over the bodies, you’ll see that it just tore up the linen. This is big trouble.”

“Why?”

“Because it got a taste of human flesh. It needs to be shot, because now it knows God created man full of nutrients, something we forget from time to time.”

“Will the shepherds shoot it?”

“Yes. That is how it will be,” said Abdelkarim, who then, from a pocket in his robe, and extracted a stapler. He wrapped the linen around the man again and stapled it together. The snapping sound echoed throughout the chamber.

“Later, if the convoys return, we can rebury them with more respect. The Shura will designate a place in the city for a new cemetery; this is something we have already discussed. Now come on and let’s get hold of him.”

The body was stiff and easily lifted into the chamber.

We found four more bodies lying on the ground, and we moved each one. While we were carrying the last one, I felt something under my foot. I looked down and saw a 9 mm shell casing. After we put the body in its place, I picked the object from the sand.

“You know, I’m thinking about how Abdul Muhyee said he couldn’t take out the dog with a bullet,” I said, showing Abdelkarim what I’d come across. We gathered all the spent casings we could find.

“An animal of this size can’t be taken out with pistol ammo,” he said decisively.

I suddenly had a bad feeling, knowing that we didn’t have a single firearm between us.

Abdelkarim again stooped over and began to count; and then, with long strides, walked over to the cave wall.

“Poor Abdul Muhyee never was the best shot in town,” he said and pointed out the chip marks left by the bullets in the stone. The goatherd couldn’t even hit a dog. We shared a smile and got ready to head home.

The sun was setting when we arrived back in town, and dark fell soon thereafter. The bike turned onto the road that led to the mosque. In front of the iron gate stood a crowd. They parted so we could enter. The women wailed loudly, and the men stood in a circle around where the boy’s mutilated body lay. The shepherd had died clutching the imam’s rifle.

With fingers numb from the cold I slowly buttoned up my galabeya. Beyond the window the light of the torches flickered. It was already cold enough to see my breath in the room. The hills cast shadows over the courtyard. Down there the men were talking, though their words were distorted beyond comprehension from the wind. My face burned from shaving. I gazed into the bowl of water on my bed for a moment, and then took off my leather jacket and shirt.

Abdelkarim insisted that I take part in the assembly of men in the mosque, and he’d loaned me his celebration galabeya for the occasion, the one he had purchased for his pilgrimage to Mecca. It was worth more than my camera and equipment combined.

“For my greatly esteemed guest,” he’d said, when he laid the robe in my hands. I was slowly getting used to how on certain occasions I couldn’t show up in my Western clothing. Abdelkarim’s friendship had greatly improved the town’s esteem of me; I got fewer suspicious looks, and even the mujahideen mumbled “Peace be upon you,” if we happened to meet at the market.

I didn’t want to be late. Abdelkarim had calmed the terror-stricken crowd, and invited them to an assembly so they could discuss the case of the wild animal that was hunting among the hills. The men were already gathering. I fastened my belt, adjusted the jambia, the traditional dagger, and began down the stairs. By the time I got to the courtyard, everybody had already gone into the mosque. Only the clatter of the rifles that were hung on wall hooks could be heard in the wind. Abdelkarim didn’t allow firearms in the mosque. I quickened my pace and took off my shoes. Inside sat about seventy men, loudly arguing. Abdelkarim waved me over.

I sat next to my host and quietly observed as some men squabbled, while others took to examining the corpse. They all agreed that whatever animal had done this to the shepherd needed to be hunted down. The town butcher, a mustached, potbellied man named Badr al-Din, shouted loudly that they should start for the hills at once, because “every lost hour is a waste.” Many approved of his plan, though others thought it was a trap. A heated argument arose, with urgent gesticulations followed by many threats: exactly how Arabs typically argue. Abdelkarim strained to keep the tenor calm.

The ruckus lasted until Nurdeen, a fifty-year old, one-eyed mujahid, stood up. He wore a gray jellabiya and a long black scarf around his neck. His beard fell the length of his chest and his one good eye shined white with light. The old man had fought in the battle for Marjah, on the Afghani Taliban side. There he had lost his eye in a rocket attack; at least that’s what he told Abdelkarim. They were old adversaries, because he believed my host was too lenient in questions of faith. He didn’t go to Friday prayers in the mosque, preferring to pray at home, with the followers he came across in the town. He only attended the assemblies.

The old mujahid waited quietly for a few moments, casting his gaze over the others until they fell silent.

“Is it not possible that because of our guilt God has punished us?” he asked those gathered, his voice rising.

A shadow of worry passed over Abdelkarim’s face. The room had gone totally quiet.

“We need to think about why he is punishing us with such a grave blow,” the old man put forth.

“My respected Nurdeen,” said Abdelkarim, his voice stiffer than usual, “I note your concern, but the signs are unequivocal. A wild animal is hunting in the hills. Because it is night, and its tracks will be hard to follow, I suggest we set a trap tomorrow.”

Many of the men voiced their approval.

Nurdeen’s face tightened, but he sat back down without another word. Badr al-Din offered to hunt down the beast himself, along with his boy. The greengrocer, Safiy-Allah, also volunteered.

Finally, they decided that at dawn, after the Fajr prayer, the small party would leave for hills.

I turned toward Abdelkarim and asked if I could go with the hunters. I wanted to see the hills again, and the desolate countryside. My host nodded, and said loudly, “Our foreign brother is volunteering to help with the wild animal’s killing.”

His announcement wasn’t greeted with undivided enthusiasm. I saw old Nurdeen shake his head disapprovingly, and look at me with spite. He hated everything and everybody from the West. To him, I was vice on two feet.

Badr al-Din decided the question. “Every bit of help is useful, from wherever it arrives. We agree to wait for our foreign brother in front of the mosque tomorrow morning,” he said and, moreover, he appeared convinced that they really did need my help. The assembly, as always, ended with communal prayer.

I couldn’t sleep from excitement, and by daybreak I was in the prayer room, ready to go. Abdelkarim and I repeated the Fajr prayer, and then went out to the front of the mosque. The street was empty. We stood shivering wordlessly next to each other, until finally Badr al-Din and his group appeared on the main road. They wore rough baize jackets and scarves tied around their heads. Safiy-Allah led a mule loaded up with gear. They greeted us with a “Peace be upon you.” Abdelkarim handed me a shoulder bag. His wife had packed me some salted goat meat, onion, and bread. Off we went.

It was cold, and we had already reached the hills by the time the sun appeared. We didn’t speak much along the way. Badr al-Din asked if I wanted a gun. When I said yes, he handed me an old World War I rifle. I thanked him and rested its rust-covered barrel on my shoulder.

After a three-hour walk we arrived at where Abdul Muhyee’s body had been found. Animals were grazing there on the grasses that grew between the cliffs. The boy’s blood had already dried in the sun; only the carcass of a goat with its throat torn out marked where the shepherd had been attacked.

Badr al-Din examined the tracks for some time. They ran north and turned off the dirt path. We followed them under the fiery, mercilessly hot sun. Sweat flowed into my eyes, and my shirt stuck to my skin. One of Safiy-Allah’s teenage sons gave me his scarf to tie around my head.

Badr al-Din lost the dog’s tracks on a plateau. It was decided that we would ambush the animal there. It was a good place, because we could hide behind the rocks that abutted the hill, and the wind would carry the smell of blood in the direction the dog had headed. Each man grabbed a weapon from Badr al-Din as he unpacked the mule: modern Egyptian AK-47s, their barrels shining with oil. After we got situated, Safiy-Allah led the mule to about a hundred feet in the distance and tied it to a brittle, dead tree. He took his knife out and cut lengthwise into the animal’s flank. The wound wasn’t deep, but enough blood flowed for predators to smell. For two hours we lay on our stomachs between the rocks, waiting for something to happen, but the blood just drew flies, which flew in and out of the mule’s open wound. The two teenage boys next to me began to chatter. Safiy-Allah and Badr al-Din ate the food they had brought. Time moved forward slowly. The moon appeared, and again we could see our breath as the rocks crackled with cold. Badr al-Din said that we would wait half an hour longer. The two teenage boys were already asleep in between the jutting rocks. I leaned against a boulder and gazed up at the moon. It appeared bigger than I had ever seen it. I could clearly make out the craters. Everything looked good bathed in its light.

First we heard a howling, then another in response. Soon, the night was filled with jackals calling to one another. The mule nervously clomped its hooves and pulled at its tie. I caught sight of five jackals approaching, their heads dropped cunningly, stalking the smell of fresh blood.

The men clutched their guns and waited. The animals were still too far away to get off a good shot. But before the jackals could attack, a large-bodied dog appeared on the hillside. Its huge silhouette stood out against the moon, and we could see the gleam of its tusklike fangs. When it began to bark, its breath came out in puffs that looked like smoke. At the sound, the jackals began to beat their tails. We watched, stunned. Badr al-Din was the first to regain composure.

“God is great,” he shouted, then began to fire. The others followed.

A barrage of gunfire scorched the incline. The cliffs showered stones—the mule was hit—but the black dog stood unmoving. He waited until the men emptied their cartridges, then skulked back into the darkness from which it had come.

“God is great, God is great,” the men cried in terrified voices.

Stumbling on the rocks, we started back to town, leaving the mule’s corpse behind. Nobody had an explanation for what had happened.

Abdelkarim was still awake when I got back; he had been waiting for me. I explained to him what happened, then fell into bed fully clothed.

The next morning I found him in the prayer room, absorbed in the Hadith. The book he held in his hands was probably two hundred years old. Abdelkarim was wearing same galabeya I had seen him in yesterday.

“Last night the beast attacked and killed a woman named Khulud, and two of her children are in the hospital,” he said. “One remaining child has yet to be found.”

“Was it the black dog?”

“That is what they are saying.”

“Now what?”

“I have to convince them once and for all that the dog must be killed.”

The imam stayed buried in his book all day and didn’t even emerge from the prayer room for lunch. I didn’t want to bother him. Nor did I want to bring up the assembly that was planned for that evening.

The men, superstitious and fearful, listened to Badr al-Din’s account of the hunt. The butcher, shaking a fist in the air, closed his speech by stating: “I am saying for certain that this dog is not of God. Safiy-Allah, his boy, and even the foreigner were witnesses.” Terrified shouts of, “God is great!” filled the room. Abdelkarim sat palely next to me, stroking his beard. He stood, and then addressed the men.

“My brothers. Listen to me, my brothers,” he said. “We need to put an end to this dog before it kills again.”

A numb silence descended. I could hear the oil lamp sputter and the clatter of the rifles against the wall of the room.

Khaldun stood up. “It’s not certain that the dog is not of God,” he said, looking over the attendees and then staring spitefully at Abdelkarim. “On the contrary. I think God sent this animal to call attention to the fact that we have strayed from the proper path. Those it killed, they were all guilty. Have you forgotten how many times you saw the boy intoxicated on khat? How the husbandless Khulud was attacked, and her children as well?

Men around the room began to nod.

“We have to put the question to ourselves: Why is God punishing us? The answer is here in front of us. It is because we have become lazy in our faith. Because God’s commandments aren’t fulfilled without ere. Because we gamble, we don’t supervise our women’s morals, and we let foreigners into our homes. It is time to renew our submission to God, and examine the town’s morality. Only in this way can we fend off these blows.”

Shouts of “God is great,” broke out among the attendees. Many of those gathered stole a glance at me. Others hugged Khaldun and thanked him for showing them the light.

Abdelkarim sat wordlessly next to me, and when the tone had calmed, he stood.

“Excuse me Khaldun, are you suggesting we improve our morals in the way they do in Marjah? Beating our women with sticks if their faith slackens? Stoning the criminals?”

“If this is the price of deflecting these blows from our heads, then yes,” shouted the old man from his place. The surrounding men nodded.

“And if I guess correctly,” Abdelkarim said, “you would nominate yourself to head a council of morality? It is known that you have had some practice in these matters.”

“I only hope the brothers are humble and pious enough to carry out the task,” said Khaldun.

“Yes, yes!” shouted the room.

Abdelkarim cleared his throat and continued. “Well, I believe you are mistaken, my respected Khaldun. We must kill the dog no matter what.”

“Why need it be like this? Why is this how you want it?”

Abdelkarim stepped up to the butcher, Badr al-Din. “What color was the dog?” he asked. “Tell us brother, what color was the dog?”

“Black,” answered Badr al-Din, confused. “Black as night.”

Abdelkarim leaned over and took the Hadith in his hand, the one he had been reading all day. He opened it and turned to Khaldun.

“We need to kill the dog, because the prophet, peace be upon him, commanded it so. It says so in the Hadith: ‘Kill the black dog, because the black dog is the devil.’”

He spoke calmly, and didn’t raise his voice for even a moment. Again, quiet fell on the room.

“Respected Khaldun, are you suggesting that we shouldn’t follow the Hadith?”

“I am not saying anything like that,” the old man grumbled between clenched teeth.

He rose and left the room. Many followed. We could hear a religious song rise from the courtyard, their voices echoing through the alleyways.

“Who volunteers to do away with the dog once and for all?” asked Abdelkarim when quiet returned.

“Tomorrow morning we will begin for the hills again,” said Badr al-Din. You could see fear on his face, but that he was gathering his strength. He liked Abdelkarim and had faith in him. Next to him, Safiy-Allah nodded.

“No, brothers,” said Abdelkarim. “The beast is already hunting here in the town. We need to kill it here.”

The plan was easy: the volunteers would hide by the hospital, where the smell of blood would be strongest. The men agreed.

The street was empty when we set off. The sky was dark; not a bit of light seeped in. Badr al-Din and Safiy-Allah went in front, clutching firearms in their hands. Abdelkarim and I took up the rear. I looked over my host’s face in the darkness, but it gave away nothing about what he was thinking. I took out two cigarettes, lit them, and offered him one, but he didn’t take it.

“Pray, brother, that we can kill the dog,” he whispered as he pulled back the bolt of his Mauser, “or else Khaldun will have his way with this town.” The rattle of rifle bolts locking in rounds echoed along the street.

We didn’t speak again until we arrived at the hospital. It was a whitewashed, two story structure. In the air hung the effluvium of disinfectant mingled with that of blood. The Dutch doctors had left when the government began a heavy shelling offensive, and since then the barber had been seeing to the wounded. The sun-beaten Red Cross insignia was the only reminder that foreigners once lived here. We could see the bodies of the moribund and unmovable on the blood-stained plank beds, asleep and breathing heavily under the influence of raw opium.

The hospital entrance was covered by a gray sheet. Badr al-Din was the first to enter. Because of the strong smell he tied his scarf around his face. After the first attack, the locals had evacuated anybody who could move, so the hospital was almost empty.

Badr al-Din and Safiy-Allah positioned themselves by the sickbeds on the first floor. Abdelkarim and I went to the rooftop, where we had a good view of the area. We took our positions and waited.

“It is possible it won’t come,” I whispered to Abdelkarim after a tense hour. The moon was hidden behind black clouds and a strong wind blew across the hills.

“It must come,” he answered, “in the name of God.”

Another half hour had passed when we finally heard a screeching coming from a nearby street. The black dog, as though it had appeared from thin air, stood in the square by the entrance. Blood dripped from its mouth. At its feet lay the body of a girl.

Badr al-Din and Safiy-Allah came bursting out of the hospital, then opened fire on the animal. But the dog didn’t flee, it just held its head toward the moon and began to howl, making a deep, thunderous sound that echoed through the streets. Twenty or so snarling mongrels appeared at the call. They stood behind the black dog and stared at Badr al-Din and Safiy-Allah with pitch-black eyes.

The black dog’s muscles tensed and its teeth snapped as it sprang toward the two men. The pack followed.

“God! God!” yelled the men. They lowered their guns and stood paralyzed by fear.

But Abdelkarim hadn’t lost his calm. He lifted his rifle to his shoulder, aimed, and let a bullet fly. It found the black dog.

The animal, which had until then seemed like it was swimming in the air, stopped short. It stood still and lifted its head. Badr al-Din and Safiy-Allah raised their guns again and began to fire. They dropped six of the mongrels, one after the other.

Transfixed, I stared at the black dog. It was gigantic. It shook its head and with a yowl charged Badr al-Din, blood streaming from its flank.

Abdelkarim’s second shot also found its mark. The black dog stumbled. It tried to stay on its legs, but couldn’t. The remaining mongrels from the pack fled when the black dog fell. It was still breathing when we arrived at the building’s entrance. Abdelkarim put a bullet in its head, and only after that did we examine the beast from up close. It was a mongrel, but unlike any I had seen before. It was probably over two hundred pounds. Countless old scars covered its muzzle, and flesh had overgrown both its ears. That’s why it hadn’t been afraid of the gunfire. It was deaf.

People filled the streets. Badr al-Din and Safiy-Allah threw the dogs’ bodies in a cart, and the crowd accompanied them to the mosque. They left the bodies in front of the gate, so that in the morning the whole town could view the slain devil.

Badr al-Din invited everybody to celebrate the dog’s killing, so we all went to his home. Abdelkarim, however, didn’t stay with us. He begged our pardon, but he stated that he was exhausted and needed to return to the mosque.

I woke up to silence. I looked at my watch: it was four in the afternoon. The celebration had lasted until dawn, and I’d gotten home at sunrise.

I went down into the mosque, but couldn’t find Abdelkarim anywhere. The house was totally empty. I went out into town, but the streets were deserted as well. It wasn’t until I arrived at the hospital that I found where the crowd had gathered. There, where they had killed the dogs just yesterday, people were lying on stretchers, moaning, their torn clothing bunched up around their sweating bodies.

“What happened?” I asked a barefoot shepherd boy.

“It’s a plague,” he said. “Lots of people have high fever. They’re throwing up and are breaking out in sores.”

“Have you seen the imam?”

“He is inside with his two girls.”

I cut through the crowd. The room was packed. The infirm lay on the floor or were propped against the wall, shivering with fever. I looked for Abdelkarim. I found him on the second floor. He sat on the tile next to a dirty mattress. On the bed lay his two girls, both unconscious. He didn’t notice me. His eyes were glazed over and his face shook as he wept. I touched his shoulder. He looked up at me but it was as if he didn’t know who I was. “We shouldn’t have killed the dog,” was all he could say.

I didn’t know how to respond. I returned to the mosque. It was obvious that I needed to leave the town while I still could. In front of the mosque stood the cart, where we had laid out the dogs’ corpses. I looked for the black dog, but couldn’t find it anywhere.

____________________________________________________________________

SÁNDOR JÁSZBERÉNYI (1980) is a Hungarian writer and Middle East correspondent who has covered the Darfur crisis, the revolutions in Egypt and Libya, the Gaza War, and the Huthi uprising in Yemen, and has interviewed several armed Islamist groups. A photojournalist for the Egypt Independent and Hungarian newspapers, he currently lives in Cairo, Egypt. Born in 1980 in Sopron, Hungary, he studied literature, philosophy, and Arabic at ELTE university in Budapest. His stories have been published in all the major Hungarian literary magazines and in English in the Brooklyn Rail, Pilvax, AGNI and B O D Y. His first collection of short stories, Az ördög egy fekete kutya (The Devil is a Black Dog), was published in late 2013.

The Devil is a Black Dog, translated into English by M. Henderson Ellis, is being published in December 2014.

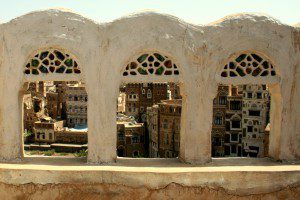

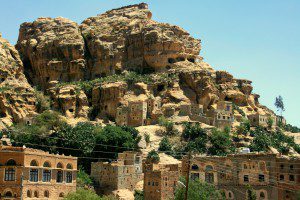

Photographs in the story by Sándor Jászberényi

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

M. HENDERSON ELLIS is the author of the novel Keeping Bedlam at Bay in the Prague Café (New Europe Books, February 2013). He lives in Budapest, where he works as a freelance editor at Wordpill Editing, and is a founding editor at Pilvax magazine.

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Sándor Jászberényi:

Fiction in B O D Y

More fiction in B O D Y

A short story in Pilvax

A short story in The Brooklyn Rail