THE GREAT WAR

(an excerpt)

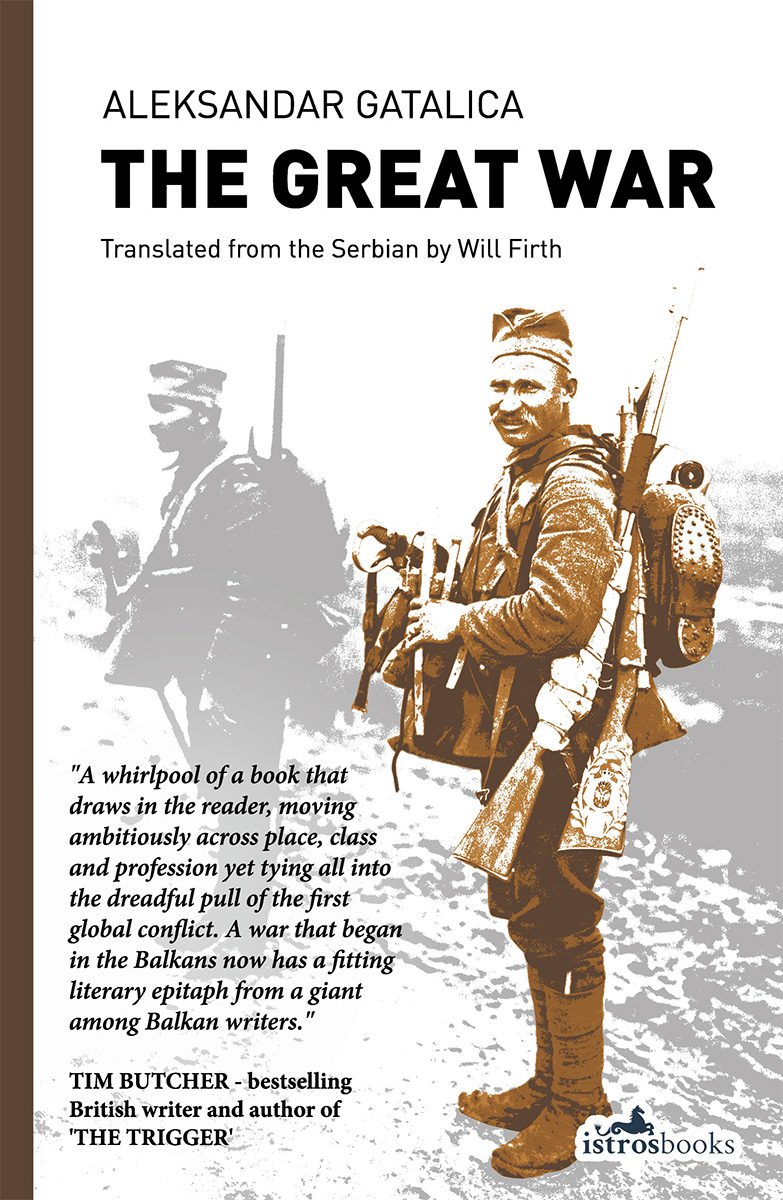

The Great War

The Great War

A novel by Aleksandar Gatalica

Translated from the Serbian by Will Firth

Published by Istros Books

The fetid air of disaster, fateful decisions, and the hope of salvation hung over the streets and canals of Moscow, Kronstadt, and Petrograd in those last days of 1916 like the smell of decay and the taste of transience. Apparitions flitted past beneath the streetlights: half human, half idea. The collapse of the system was accompanied by the downfall of its faithful, so responsible figures discharged their duties with furrowed brows and pursed lips, praying that their labours would make the difference between triumph and disaster. Everything hung by a thread from early morning till night. It was either victory or total defeat. The light of Christian Orthodoxy on the eastern marches of Europe or the darkness of Asia and Levantine degradation. Tomorrow was another day. Demons lurked behind every corner, and the obstacles on the path ahead were so numerous that not even the staunchest defenders of the Russian monarchy could foresee its future.

The most persistent troublemaker, the most blatant menace and negator, was Rasputin, or ‘Our Friend’, as the tsaritsa called him. ‘Our Friend’, however, was only a friend of the German-born tsaritsa and perhaps the tsar. For all others he was a deathly threat and had to be eliminated. Orgies, immorality, the pretence of healing Tsarevich Alexei’s haemophilia, the disgracing of the royal court and poor counsel were pushing the Empire from the Kievan gate of Europe straight towards the postern of Asia. A handful of loyalists therefore decided to kill Rasputin. The decision was taken. Their brows were furrowed. Again, the outcome would determine the difference between triumph and disaster.

The 16 December 1916, by the old calendar, was set as the decisive day. A lot of sixes in one date — three, even, if you consider the nine an upside-down six. But the job had to be done because, as with so many urgent matters, there was no one to accomplish it other than the brave conspirators. The group was headed by Prince Felix Yusupov, a strange man, who often went around his house wearing women’s clothes. Yusupov was the sole surviving son of Russia’s richest woman, Princess Zinaida, and he lacked for nothing. He had already tried to poison Rasputin once, but the cyanide did not affect him. It turned out that the ‘man of God’ had the habit of taking a little cyanide with his dinner every day. Starting in 1909, he took grain after grain of the poison and gradually became immune to the greatest murder weapon the nineteenth century had known.

Therefore, in Yusupov’s second attempt, Rasputin would be killed four times over. All this was possible in Russia — and more: someone could be killed five or six times for symbolic or ritual reasons. But Yusupov received a visit from an old Oxford friend who explained that the British crown wished to participate in at least one of the four killings of Rasputin in order to strengthen the two countries’ alliance in the Great War. Yusupov agreed, and his ‘old Oxford friend’ sent the requisite instructions to London. He asked that an accomplished assassin be sent, and everything went according to plan.

In history, this tale begins one cold night with heated carriages clattering out onto the snowy crystal of the Petrograd cobblestones to take Rasputin to Yusupov’s palace by the River Neva under the pretext that Yusupov’s wife Irina urgently needed the help of the seer’s ‘hot hands’.

But at this point we must go back; the tale actually begins much earlier with the accomplished British agent Oswald Rayner setting off with a wicker suitcase on a journey from London to Russia — a long journey even in peacetime, and now even longer, given the need to detour the theatres of war. But Rayner was not to be discouraged. This was to be his longest journey with the least luggage. He took with him a change of winter and summer clothes, a tube of toothpaste, a bar of shaving cream and a brush, a photograph of a young woman in an oval medallion and an ‘envoy’ of the British crown: a Webley .455 revolver, which was to leave a souvenir from the Isles in Rasputin’s body.

He departed on 7 December 1916 by the old calendar, or the day before Christmas by the new, without any Yule cheer or send-off, heading from London’s Victoria Station by rail to Dover. He stared through the window of the carriage at the relentless rain pouring down on the meagre British vegetation. No one was waiting for him in Dover. He changed from the train to a ship and started through the English Channel for the north of Spain by the same route which the Royal Navy under Nelson had taken on its way to defeat the Spanish fleet at Trafalgar. In Spain he spoke Spanish. He bought a ticket to Barcelona. Again he was on a train, which slowly made its way through orangehued España. He saw trees laden with oranges and no one to pick them. In Barcelona he took another train, for the Côte d’Azur. He lied to an elderly lady and her granddaughter fluently in Spanish. In Nice he boarded a bus. He paid the driver in cash and thanked him in French, which he seemed not to speak nearly as well as Spanish. So he stayed silent in the bus. He stared into the mighty blue of the Mediterranean and felt nothing—neither satisfaction, nor sentimentality, nor sadness — when his gaze drowned in the expanses of the sea. He entered Italy at the little town of Ventimiglia. He boarded his third train on the Continent, which took him through pleasant, rustred Tuscany and further into the gnarled south. In Brindisi he boarded another ship and travelled to Corfu, where he slept one night and didn’t talk with anyone, and then on to Salonika. There, Rayner finally heard English again from British diplomats. A car was waiting for him. This inconspicuous automobile with a high windscreen and folding roof had one important feature: it was equipped with two pairs of licence plates, Greek and Bulgarian. He immediately set off on this next, far from easy leg of the journey. Near the city of Kavala the driver removed the licence plates. While he was putting on the new ones, Rayner changed from summer into winter clothing. Neither of the men spoke a word in English or any other language. The car set off again and drove another seven hours through the night. It stopped at the coast of the Black Sea. Here at the town of Tsarevo, before dawn, Rayner boarded the Russian torpedo boat Alexander III, which took him to Odessa. Then, mingling with the ordinary Russian travellers, he went by bus to Kiev. He changed there and travelled on through the western Ukraine, and then caught a third bus destined for Petrograd.

It was 16 December 1916 by the old calendar, shortly before midnight, when a heated carriage brought Rayner up to Yusupov’s festively illuminated palace. Rasputin was already there. The Englishman went down the wooden stairs into the cellar. The boards creaked beneath his hurrying feet. The ‘man of God’ had already been killed twice: he had been poisoned with cyanide again, this time with a far larger dose, and then stabbed with various sharp objects — knives, forks, and broken glass. Now it was time for the representative of the British crown to kill him a third time. Without speaking a word, Rayner took out the Webley .455 and fired one shot into Rasputin’s head. Then he returned the gun to the wicker suitcase and shook hands with the small conspiratorial committee, although he didn’t know anyone. In addition to the host, those present were Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich for the Romanov dynasty, Lieutenant Sergei Sukhotin for the Russian armed forces, the parliamentarian Vladimir Purishkevich for the State Duma, and Dr Stanislav Lazovert, disguised as a valet, in the name of medicine.

Dr Lazovert ascertained biological death, but Rasputin still had to be killed a fourth time. The conspirators dragged Rasputin’s body across the floor. His wild hair and beard snagged in the fringes of the heavy carpets. The killers tore out the snarls and continued to drag him along like a wild boar. They all left the building; the Russians made for Petrovsky Bridge to drown the ‘man of God’ and thus kill him a fourth time, while Rayner immediately started on his journey home.

He left without any send-off, through the enamelled Russian night which seemed it would never see the day. Prince Yusupov’s heated carriage took him to the bus station. Mingling with the ordinary Russian travellers, Rayner caught the first bus to the Ukraine. He changed to a second, which made its way through sleepy Ukrainian towns, and there among the creased faces of the passengers he saw in the New Year by the Western calendar. A third bus then took him to Odessa, where he boarded the Russian torpedo boat Alexander III and was trans-ferred over the Black Sea to Bulgaria. At the coastal town of Tsarevo he switched to a car. The inconspicuous automobile with a high windscreen and folding roof had one important feature: it was equipped with two pairs of licence plates, Bulgarian and Greek. The driver started the motor and they immediately set off on this far from easy journey. Near the city of Kavala the driver removed the licence plates. While he was putting on the new ones, Rayner changed from winter into summer clothing. Neither of the men spoke a word in English or any other language. The car set off again and drove another seven hours through the night to Salonika. There Rayner finally heard English again from British diplomats. He changed vehicles once more and was driven south to Vouliagmeni. From there he travelled on the second ship of his return journey, via Corfu where he slept one night and didn’t talk with anyone, to Brindisi, the ‘gate to the Adriatic’. Here, for the first time on the return journey, he boarded a train, which wound its way through the gnarled landscape of southern Italy towards pleasant, rustred Tuscany and further north. He entered France at the little town of Ventimiglia and boarded the bus to Nice. He paid the driver in cash and thanked him in French, which he didn’t speak nearly as well as Spanish. Therefore he was silent in the bus. He stared into the mighty blue of the Mediterranean and felt nothing—neither satisfaction, nor sentimentality, nor sadness — when his gaze drowned in the expanses of the sea. In Nice he bought a ticket to Barcelona. Again he was on a train slowly making its way through orange-hued España. He saw trees laden with oranges and no one to pick them. In Spain he spoke Spanish. He lied fluently to a young lady and her niece. In Barcelona he took another train to the north of Spain. There he boarded the third ship of his return journey, plied the waters which the Royal Navy under Nelson had sailed on its way to defeat the Spanish fleet at Trafalgar, and entered the English Channel. No one was waiting for him in Dover. He travelled on to London by rail. He stared through the window of the carriage at the relentless rain pouring down on the meagre British vegetation. At the end of his journey he arrived at Victoria Station. There was no welcome home or anyone waiting for him on the platform.

It was the evening of 6 January by the new calendar and Christmas Eve by the old when Rayner returned to his house in Royal Hospital Road. There he opened the wicker suitcase and took out his change ofwinter clothes, an empty tube of toothpaste, what was left of the bar of shaving cream, a brush, the Webley .455 revolver, and the photograph of a young woman in a small, silver oval. He kissed the photograph, prepared the winter clothes for washing, cleaned the gun and went to sleep. All was quiet in the house in Royal Hospital Road, and after his sixteen-day journey undertaken because of one single bullet, Oswald Rayner slept like a stone until morning.

____________________________________________________________________

ALEKSANDAR GATALICA was born in 1964 in Belgrade. He has published five novels to date, including The Lines of Life (Linije života, 1993) The Invisible (Nevidljivi, 2008) and The Great War (Veliki rat, 2012), which won all four of Serbia’s major literary prizes upon its initial publication (NIN award, ”Meša Selimović” Award, National Library of Serbia Award, Best-selling book in 2013 in Serbia). He has also published five story cycles, including: Mimicries (Mimikrije, 1996) and Century, One Hundred and One Histories of a Century (Vek, sto jedna povest jednog veka, 1999).

A translator from Ancient Greek, Gatalica has published translations of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound, Sophocles’ Oedipus as well as the first Serbian translations of Euripides: Alcestis, Iphigenia in Aulis, The Bacchae, along with Sophocles’ final play Oedipus at Colonus. An active music critic and writer, has written on music for several radio programs, and a Serbian daily newspaper. As a music writer he published six books, among them: Rubinstein versus Horowitz (Rubinštajn protiv Horovica) in 1999 and The Golden Age of Pianism (Zlatno doba pijanizma) in 2002.

The Great War is having its UK publication launch on November 10 in London.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

WILL FIRTH was born in 1965 in Newcastle, Australia. He studied German and Slavic languages in Canberra, Zagreb, and Moscow. Since 1991 he has been living in Berlin, Germany, where he works as a freelance translator of literature and the humanities. He translates from Russian, Macedonian, and all variants of Serbo-Croat. His website is www.willfirth.de.