LISTEN TO THE VOICES AT THE FAR END OF SUMMER

(an excerpt)

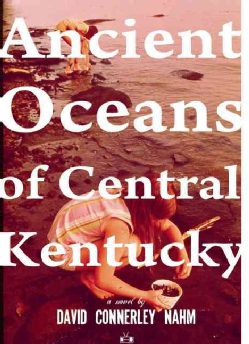

Ancient Oceans of Central Kentucky

by David Connerley Nahm

Published by Two Dollar Radio

August 2014

IN THAT LAST MOMENT, the brilliant catacombs of space, the gathering light. The girl in the purple dress is a parasol. She held out her hand, cupped, ready to catch rain. The streets were half clusters of disappearance. Half clusters of broken wives.

![]()

The girl took Leah by the hand and they crawled over the fence. Cheeks and shoulders dotted with drying salt-sweat. Flickering eyelid of a deer, the pink tongue of a toad, the mirror of sound. Beneath a pregnant galactic vista, an eternity of pauses, never more than a sheet drawn across the sun. Fallen trunks of trees, hollow and rotten and some boys that the girl met at the movie theater. Leah leaned forward and she breathed hot breath and saliva back and forth with a boy from another county while a few feet away the girl watched and laughed, having dared her. The air is in bloom with the splendid riot of the bright green cow shit that surrounds them. On the other side of the pasture, the slumping wall, dry stacks of stone and beyond that, the Old Country Club. Air licks the thin blades of dry grass. The boy hoots. Leah felt like weeping, but kept thinking of the girl watching. This or another Sunday of doing nothing but watching Hayley Mills movies in the living room while her mother sleeps on the couch. She never made it to the Old County Club to read the graffiti. Never beyond even that, to the sunken stream, blocked from sight by a break of trees, crackling water full of garbage and shaded forever. Hayley Mills looks at her, but she cannot hear.

![]()

The girl opened the door of an abandoned building and Leah followed. The girl had an empty water bottle of bourbon in her coat pocket. The hall was nearly completely dark. The only light came in from a window at the farthest end from the stairs. They didn’t hear anyone and there were no lights on in any of the rooms that they could see, but then, they could hear singing in the dark, but too faint to name. Both realized that this meant that whoever came up, if they were still there, was sitting in the dark. The thought, happened upon at the same moment by both, was too much and rather than sneak out, they bolted for the stairs, hit the door with a clatter and tumbled down the steps like marbles. It was only when they were outside on the empty Crow Station streets that they laughed, a torrent of laughter that neither could suppress.

![]()

On her back, stretched on a fallen tree trunk, listening to the clatter of water over rocks, alone, Leah stared up into the now green canopy of trees in the woods where she’d wandered, across empty fields and past the ruins of old farmhouses and the Old Country Club. She matched her breath to the lapping and the crackle of decaying undergrowth and felt her eyes dry out. One of the still standing spires of the decaying clubhouse cluttered with sunlight in the distance. She had nothing planned for the rest of her life beyond this. A warm breeze passed through everything, through her. She could feel the rotting bark scraping her bare calves.

![]()

Her neat desk, the case files and the telephone and the cheap toy car that she kept by the computer monitor that looked just like her car.

The telephone rang, but she let it go to voicemail. On her wall hung a framed copy of the article about her from last week’s newspaper. The women in the office had given it to her as a gift. The telephone rang but the person left no message.

![]()

The wind blew and caused dry leaves to whisper and she was walking along the bank of the stream that ran through the trees by her apartment complex. A black snake hurried from her path, startled and running away like water.

She remembered: They were cutting through a pasture, slipping down between trees to the stream and there had been a snake, green mud and mossy rock. The girl laughed and they took after it. The snake, caught in a crotch of roots. They tossed rocks, laughing, until it was dead, and then something moved through the trees and they, without a word, ran home.

The summer days grew shorter.

![]()

They lay in the grass, the green blades rising above them like spires or green teeth in a blue mouth. Leah felt her legs sink into the soil and her friend told her uncanny things about Pennsylvania and about her family, most of which Leah had a hard time believing. All mired in the blue around her and smelling the salty smell of the clouds.

That night Leah looked at her own face in the bathroom mirror after her bath, below the bright light of bare bulbs. She looked at her neck, pulling the hair aside. The faint shape almost looked like something. A figure moving though fog, nearly resolving into something she could name, but always elusive.

Grass uncut and ankle high. Sirens, chirping sparrows and cardinals, gutter-tongued hollers of children in distant neighborhoods playing in the street. The deep-earth thrum of hundreds of lawnmowers. The scent of gasoline and billowing grass fills lungs. Spores that cling to legs, arms and eyelashes. Clusters of dandelion seed taking to sky like infant spiders. The opening eye, the black eye, the widening iris.

But each letter can have a meaning of its own. They can be rearranged to make other names with other secret meanings. Certain letters in a certain order can bring people to life from lifeless garbage. The man showed the child in the parking lot of the motel some of the things he’d cut free from the wood.

As stars cooled and dust became the Earth and as the Earth cracked and became towns and as this town divided and divided again and became his house and his neighborhood, the entire history of life deeper than living is written in him.

![]()

Leah looked at her friend’s flushed face. Dew dried on lip. The edges of a small pool in the depression of her throat crackled as the warm sun peaked over the soft knoll. Her skirt was bunched around her knees, her left leg bare against the cool shifting grass, kicked out to the side. The left arm lay against her breast, the wrist dangling limp.

There was ink on her fingers. They were quiet. Her legs bled green turf below her, upon her, so that she could be nothing more than graying spores in the crevices in the white paint on the swing, still in the breeze.

![]()

“It’s not your fault,” her friend said.

“But, listen, it is,” Leah said. “I never told anyone, but—” There was a knock at the door.

![]()

The interior halls of the church were dark, lightless but for the small all-glass walk-way in the front of the church that led to the sanctuary where moonlight and streetlamps cast half-hearted colors. The lock-in’s young legs course full speed, slicing through darkness. Heaving lungs power startled cries. Screams melt to laughter. Arms swing pillow cases willy-nilly. Hands brush against anonymous body parts. The faint scent of wintergreen gum and hairspray fills dilated nostrils. They stumble upon two bodies in the dark and a moment of confusion and a gasp and the sound of clothes being quickly rearranged. A soft squeal. The voices of two other girls. Only the faintest light from a distant EXIT sign which revealed nothing.

The children in the children’s choir huddled and whispered and giggled and swooned over one another and turned their back on those that could not sing. “I know a scary story,” one of the boys said, but no one listened. “Hey, I know a story and it is true.” He just started talking, and they started listening because it was past midnight and there wasn’t anything else to do. “So, this friend of mine, this happened to her dad. He’s like a farmer and when he was young he got back from Vietnam and his friends told him about this house out in the county. Anyway, he drove out into the county for a long time, it is way out almost to Gravel Switch, way out in the county. It’s by this old cemetery on a hill. It used to be a church cemetery, but a long time ago the church got burned down. No one knows why and they never rebuilt it but you can still see the gravestones. I’ve been by it. It’s real creepy. So, okay, so he went and parked and walked across a field to the house. Oh, so I should say that the man who built the house was insane. He had three girls and he kept them locked in the attic. His wife was dead. She had a disease that made her skin peel off. He was a religious maniac and finally he killed the girls. Maybe he burned the church too. I don’t know. But I do know that he stabbed them to death.” The boy made stabbing motions and a squishing sound with his mouth which made everyone laugh, but a nervous laugh. “That shit didn’t happen.”

“No, really it did. My dad told about that part. He has a copy of the newspaper that told about it. So, my friend’s dad crossed the field and it was real dark when he went, but he found the house and here was a full moon and you could see the tombstones on the hill, so he gets to the house and it’s really tall and kind of leaning over sort of like its sinking and he pushes the door open.” His voice withdraws, softens, very gradually, and slowing down. He lets each word out like a step on hardwood above you in a house that should be empty. He leans forward as does everyone else so they can hear. “So he looks around the house and there is a piano in the parlor with broken keys and in the kitchen there is a black stain on the floor. He had a flashlight that he brought back from the war and he ran the light over the walls. The paper was peeling off and the plaster was bubbling and ruined and rumbling and black in places from mold. He goes upstairs. One step at a time. Slowly. Upstairs there are three rooms and they are all empty mostly, except for one room has a girl’s dress hanging in the closet, a white dress, and another room has a stuffed bear in it with the button eyes ripped off of it and then in the last room there is a Bible. He walks over to it to pick it up and he can see there is a nail through it, nailing it to the floor. But that’s not the weird thing. The weird thing he notices is that the house is really clean. It is leaning a bit and the water damage on the walls you know, but there aren’t any bottles from bums or broken glass or dead bugs or anything. And the house is warm, not cold like it was outside. He goes back downstairs and finds the door to the basement, but it is locked, which he’s glad because he doesn’t want to go down there anyway. So he lays out his sleeping bag and gets in it and tries to fall asleep. It is totally dark in the house. After a while he hears a slam.” The boy knocks on the wall behind him with his palm. “He sits up but he’s not going to run. He’d been in the jungles of Vietnam and saw some terrible things. My friend told me. So he isn’t scared of anything. He waits. Then the thump comes again, from the stairs. Coming down the stairs, slowly—” He continues to thump the wall. “Then he hears something in the basement, like a table getting thrown over. The thumps keep coming, out of time with each other. It is totally dark and he can hear the thumps coming closer, just around the corner from the room where he is crouched in the corner.” His voice is barely a whisper now, everyone leaning forward nearly in a huddle, the smell of wintergreen gum blooming everywhere. “And the thumps stop and he can hear a sound, a wet sound like a fish’s mouth and he picks up his flashlight that he brought back from the war and he turns it on and—” A pause. “There is nothing there. He gets up and walks out and hears a sound in the kitchen, where the basement door is. He walks in the little dot of light bouncing ahead of him. The basement door. He hears scratching on the other side of it. Louder and louder—” He was whispering. There was no other sound. “He reaches out. The knob is cold. He turns, pulls it open—”

From the stairwell, Leah and the girl hear a roar and cry. They startle, but do not run to see what happened. Leah is crying because the summer was over. They swore to call and write, but neither did and it was only years later that Leah thought to look the girl up on the Internet at work. At first she couldn’t remember the girl’s name. Leah sat blankly for several minutes, the syllables just out of tongue’s reach. When it came to her, she spent nearly an hour tracking the girl down and finally found a blog she kept about her family. There were pictures of her five children in deeply saturated color. There were half-focused shots of the food they ate and requests for prayers for the little boy who had a problem with his lungs, his second hospitalization this year, and thanks for the gift cards to Target and Sears and Macy’s, the boy had really scored this time, she joked. Even though the woman didn’t mention it on her blog, Leah learned all about the woman’s bankruptcy as well. There was a great deal to be learned and by the time that Leah left the office, late in the night, she heard someone outside in the dark, rooting through the office’s trashcans.

____________________________________________________________________

DAVID CONNERLEY NAHM was born and raised in Kentucky. He currently lives in Virginia where he practices law and teaches at James Madison University. His writing has appeared in Little Fiction, Pithead Chapel, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, and on McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. His first novel, Ancient Oceans of Central Kentucky, will be published this August by Two Dollar Radio.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by David Connerley Nahm:

“A Selection of Uncited Sources” in Pithead Chapel

“Vacations with Mother and Father” in McSweeney’s

“Spirit & Opportunity” in Eyeshot