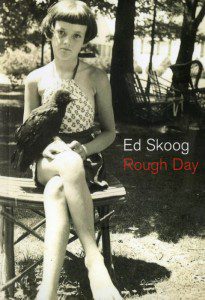

Rough Day

by Ed Skoog

Copper Canyon Press (2013)

82 pages

“all I can tell you is my own experience / and I don’t want to get sideways with that power,” Ed Skoog writes in his second book of poetry. It’s an acknowledgment—almost a rule—that the collection sticks to closely. Rough Day is remarkably free of presumption or pronouncements. The book gives us personal experience, but not in the conventional confessional or narrative sense of the phrase. Rather, it’s the experience of inhabiting a restless, questioning, capacious mind.

From the book’s opening lines, Skoog establishes questioning as one of the animating forces behind these poems:

What’s in these books that have come to me

although they don’t belong to me

I don’t think

to whom then should they be delivered

also I don’t know why

piled on my desk they came to me

mostly paperback

Not only does the book begin with a question, but it quickly calls the premise behind that question into question. This is a poetry in which nothing is certain—not the contents of the books, nor their reason for being there, nor the speaker’s connection to the objects that populate his life—and in which any statement may immediately be reversed. This uncertainty, as a parallel passage halfway through the poem shows, extends even to the speaker’s physical sense of self:

what is in this body that has come to me

although I don’t think it is properly mine

to whom should it be delivered

This is not the lyric “I” that says: This is me; this is my experience. Instead, this is an “I” that asks: What is it to be a self and to experience the world as that self?

The form Skoog uses in Rough Day is ideally fitted to this type of exploration. The poems in this book are spare, written in one-to-three-line stanzas with almost no punctuation, nothing to mark the beginnings or ends of sentences, and no titles, just one-line opening stanzas. The effect is a sense of borderlessness, ideas and observations falling down the page in an unbroken stream, each poem bleeding into the next. It’s hard to be sure where a sentence ends, or if one even does, in lines like:

beside clean socks someone dropped by

among strange friends whose eyes

I recognize as more or less mine

powerfully

I’ve halfway died

Trying to be sure about syntax, though, misses the point of the form, which marks a departure from Skoog’s earlier work. While Skoog’s debut, Mister Skylight, was often discursive and also tended to eschew narrative, it stuck to the conventions of grammar and punctuation. In Rough Day, Skoog has shucked off these conventions and achieved something like a pure language of thought. The mind rarely draws a clear line between one thought and the next, as we tend to do in writing, or arrives at anything as conclusive as a period. Instead, as Skoog does, it circles back, revises itself, or suddenly moves on to something else.

The sudden, often associative turns these poems take (“salmon are moving towards extinction / my chair is from Sweden”) seem characteristic not simply of the movement of thought but of the particular mind of this poet. The voice behind these poems has a restless, fugitive quality. In one poem, “each thought” becomes “a rope to lash / a mattress on top of my car.” In the next, Skoog offers a clue to what the speaker is fleeing:

The historical marker is a form of guilt

backward meaning

that might pull a muscle in your neck

There’s an urgent need in these poems to keep moving forward, to not get bogged down in the past. And breaking from the past is part of what Skoog is after in form as well. Early in the book, he writes:

I’m trying to find where influence end

a force emigrant in spirit

forget the old language

silent and defeated

Language is closely tied to our sense of identity. “I was nothing coming into this name,” Skoog says. In moving away from linguistic conventions, these poems strive for a new poetics—one that is at times lyrical but distinct from the lyric tradition—in order to find a new way of constructing the self.

Much current poetry that seeks to break from the lyric tradition does so through fragmentation and, in some cases, a rejection of meaning. Skoog’s associative leaps can make the poems in Rough Day seem fragmentary, but read as a whole, the book feels less like a collection of disparate pieces than like a single, continuous, wide-ranging monologue. One of the great pleasures of the book is discovering the connections that emerge between the poems. About halfway through the first of the collection’s five sections, we encounter a poem that ends:

I am practicing the language of unfinishable sentences

who wants pancakes?

and what is this pancake to you?

Those closing questions, appropriately enough, don’t really provide a conclusion to the poem, but they do comically echo the language of the questions from the book’s opening. This humor is another one of the book’s pleasures. While the poems are frequently serious, even mournful, they refuse to take themselves seriously, and the final question about the pancakes effectively punctures any pretense we might sense in questions like “what is in this body that has come to me.” The pancake, the poem says, is just as worthy of contemplation as books and the body.

Part of the brilliance of Skoog’s poetry is that, even as we’re laughing, we do start to consider the question. The pancake breakfast, after all, with its connections to childhood nostalgia, is as much a part of the physical and emotional architecture of our lives as anything else. What part of our identity does it make up?

What is this pancake to us?