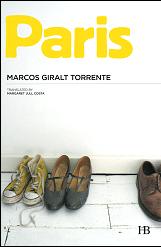

PARIS

(an excerpt)

Paris

A novel by Marcos Giralt Torrente

Translated from the Spanish by Margaret Jull Costa

Published by Hispabooks

There’s a photo we took that day, over which I linger whenever I come across it or whenever a pang of nostalgia makes me seek it out. It was taken shortly after that last scene, once we’d arrived in Burgos and walked across the deserted city. It was taken with the camera on delayed action, and it shows my mother and me, along with my father, standing by the side of an empty road. My father is looking very blond and tanned, and at his feet sits a large, old-fashioned suitcase. You would think the photo had been taken in summer if it weren’t for the snowy field in the background and the fact that the three of us are wearing overcoats (I’m clutching my blue balaclava). We’re smiling, although my father’s smile, somewhat blurred and out of focus, seems rather forced, as if he were impatient to be doing something else. They’ve put me in the middle (I come up to about shoulder height on both), and because they didn’t get the angle quite right, next to my mother you can see a concrete wall topped by a sentry box. It’s the prison wall, but that isn’t why I linger over the photo every time I look at it. It isn’t the situation, which I can remember perfectly and which, therefore, doesn’t trouble me.

When a fundamental part of the backdrop to our childhood hasn’t always been fixed and immovable, when we haven’t been shown, right from the start, how it really was, when it’s been hidden or disguised up until a certain moment and we then have to go back and learn to see it from a new perspective, nothing ever seems quite certain again. Duplicity and deceit make us suspicious, and what has just been revealed, what we’ve actually lived through and experienced, and what has merely been a matter for speculation become so intertwined that it’s hard to tell them apart. Our intuitions have as much weight as hard evidence, and while there may be occasions when those intuitions turn out to be right, there are, on the other hand, many others when we can’t distinguish what we really know from what we’ve simply imagined, where we see silhouetted figures when there’s really only a wall, a shadow, and a plant swaying in the wind. If, moreover, that revealed reality is a very unusual one which then begins to be treated as perfectly normal because it is normal for the person who has revealed it to us, the person who has removed our blindfold, then the whole confused skein of events becomes still more tangled.

I began to face up to the problematic figure of my father and what his nebulous personality meant for my mother, and I began this some time after that morning in Burgos, precisely when we had most reason to believe that one era was coming to an end and we were about to begin to lead a normal life. Up until then, any information I’d been given about him had reached me in adulterated form. My mother made use of her position as intermediary, and not only did I never doubt the excuses she gave for his absence, I also considered as normal things that weren’t normal at all. If she told me, as she did initially, that my father had had an accident and was in the hospital or, as she said later on, that he lived abroad, working for some international organization, that is what I believed and what I would say if some school friend asked me about him. It didn’t even occur to me that this was no justification for such a long separation, that he could easily have come to visit us now and again or we could have gone to see him over vacation, or he could have phoned or written a letter.

As a result of that morning of revelations en route to Burgos, I must have had a lot of questions to ask. I had to ask my mother how and why, if this was the first time such a thing had happened or if my father had often been in similar situations. She doubtless answered as best she could, although, again, I can’t remember exactly how, and her answers to my questions have become confused now with other questions and other answers given later on. I imagine, of course, that she concealed certain information from me, details she considered inappropriate for me to know. After all, it cannot even be said that the picture she painted of my father that morning was exactly faithful; it had a touch of the novel about it and, far from presenting me with the crude reality and thus tarnishing my father’s image, made him seem a romantic, even heroic figure, which in no way corresponded with what I learned for myself in between that November day when my mother revealed his secret to me and the still distant days when other secrets, as yet unimagined, would take center stage.

It isn’t what my mother did or didn’t say in the car; it’s the reason why she decided to speak that intrigues me every time I look at that photo. Because if she really thought there was a possibility that my father would change and that we would never again have to live through such a situation, why mention it when he was just about to come home? The worst of it, his long absence, was over. She could easily have gone to pick him up alone. I could understand her telling me about it earlier if I’d become suspicious or started asking questions she couldn’t answer, but since this was not the case, I don’t understand why she did it then, on the very last day, when the simplest thing would have been to go and pick him up in secret and continue the fiction. Unless, of course, she suspected that my father would not change and she wanted to cover her own back. In that case, I would interpret her gesture as an attempt to establish a pact between us, so that I could never reproach her for not having been honest with me. Her previous lie became justifiable as soon as she decided to tell me that such a lie had existed. It would not have been justifiable, on the other hand, if, over the course of time, I’d found out the truth by myself and my suspicions of further concealments had threatened to come between us.

I did not become aware of the implications of my mother’s decision, however, until much later, when my father had vanished from our lives and other things were beginning to occupy much of my imagination and my memories. I only mention it now to emphasize the importance to me of that cold, early-November morning, so brilliantly captured in that photo, because—over the years and through whatever hardships and betrayals there may or may not have been—it’s always that day I go back to whenever I feel a need to judge my mother. The moment, in short, that, for good or for ill, sealed my alliance with her. “Pay attention and listen.”

____________________________________________________________________

MARCOS GIRALT TORRENTE is author of the story collection Entiéndame (Understand Me), his celebrated literary debut, the novel París (Paris) which won the Herralde Novel Award in 1999, and the novella Nada sucede solo (Nothing Happens By Itself). He was writer-in-residence at the Spanish Academy in Rome, the Künstlerhaus Schloss Wiepersdorf and the University of Aberdeen, and was part of the Berlin Artists-in-Residence Programme in 2002-2003. His second novel was entitled Los seres felices (The Happy Beings) and his third, Tiempo de vida (Life Time) met with significant critical and public acclaim, winning the Spanish National Book Award for Fiction in 2011, and is currently in its fifth edition. His latest book, the short story collection El final del amor (The End of Love), was the winner of the International Short Fiction Award Ribera del Duero in 2011, the highest endowed award for story collections in Spain.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

MARGARET JULL COSTA has been a literary translator for nearly thirty years and has translated many novels and short stories by Portuguese, Spanish and Latin American writers, including Javier Marías, Fernando Pessoa, José Saramago, Bernardo Atxaga and Ramón del Valle-Inclán. She has won various prizes for her work, including, in 2008, the PEN Book-of-the-Month Translation Award and the Oxford Weidenfeld Translation Prize for her version of Eça de Queiroz’s masterpiece The Maias, and, most recently, the 2012 Calouste Gulbenkian Prize for The Word Tree by Teolinda Gersão.