For Tamara

by Sarah Lang

House of Anansi

104 pages

Sarah Lang’s second book of poetry, For Tamara, is an utterly compelling read. Set in a not-too-distant post-apocalyptic future, Lang’s long poem imagines a world in which all of the essential structures of society have been wiped away. Gone are the internet, books, libraries, highways, hospitals, farms, functioning governments, television. What remains: a few survivors, some of whom make it, some of whom are doomed to die later. In the midst of all this is the mother of a young girl named Tamara.

Written as a both personal letter and “survival guide” from mother to daughter, with letters to her husband and notes to herself interspersed throughout, For Tamara taps into the fear of the apocalypse that has fully permeated our culture at its most essential level. It might not have zombies, or massive gun battles with hordes of cannibals – but it doesn’t need them. The shattering of society – of everything we know – is a sufficient shock to the imagination. Again and again, as Tamara’s mother insists her daughter pay attention to the importance of preservation – not just of the means of survival, but of the reasons for it – we are confronted with the possibility of the impossibility of survival.

That both mother and daughter survive as long as they do is both a miracle and yet not a mystery. We see, page by page, line by line, exactly how their survival is accomplished. Without explicitly marking time, For Tamara follows the remains of Tamara’s family (her mother, her absent father, the ragtag ensemble of fellow survivors who arrive at their home) over the course of nine years, presumably starting from Tamara’s birth (“I think I’ll name you Tamara,” her mother writes early in the book) until she’s a young girl old enough to need her mother’s advice.

What makes this poem especially compelling isn’t the conceit of its apocalyptic vision, but its implications. It takes the idea of bombing a civilization “back to the Middle Ages” at face value and shows us what that might look like. Lang asks the question most of us fail to ask when we imagine survival in a post-apocalyptic word: How much do we really know? The answer, surprisingly, is more than we might give ourselves credit for – and therein lies the fundamental hope the underscores the nightmare of Lang’s vision.

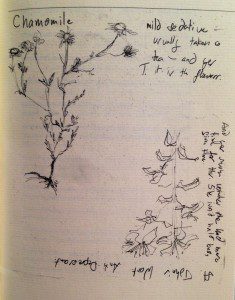

On one hand, For Tamara traces the real threat of society’s collapse by explaining what it means to live without the things we may not even realize are basic necessities (like medicines, generators, fabrics) – things very few individuals know how to create on their own. On the other hand, the ingenuity of Tamara’s mother – working from memory, from observation, or simply from logic – allows a woman who used to be a writer (that least practical of arts in a world without books, or paper, or very much ink) to transform herself into a doctor, a surgeon, a maker of painkillers and ointments, a farmer, a teacher, and a craftsperson of various talents.

By taking everything away, For Tamara puts both our mutual interdependence on one another, and our own independent abilities, in stark relief. It’s clear is that a considerable amount of research went into the writing of this poem; the book offers a wealth of practical advice, from how to make toothpaste from chalk, to how to make lye by soaking hardwood ash in water. How to test for an infection:

“Lick your wrist / then smell it. Fruity equals infection / … / Our bodies are better machines than we will ever be. / They will tell you what you have to know.”

And later:

“Smell is an excellent way to determine the type of infection you’re dealing with. / Have the patient lick the inside of his/her wrist. Smell that.”

“Before this, your Mother was a writer,” Tamara’s mother writes. “Now she is a doctor & teacher. / I suppose this still counts as writing.” There’s an interesting movement here: what she was has no place in the world she now inhabits, of all the skills of civilization it’s the least useful; but as readers, all we have is this document – without it, all of her experience, what she does know, what she’s learned, could never be transmitted or preserved. The act of writing itself justifies its place. Justifies all other knowledge, in fact, by reminding us that writing is what makes knowledge communal. Without writing, after all, her daughter would not only have no record, no connection to her mother’s mind, but no instructions, no guidance how to live and survive in the world she inherited. Writing becomes the mother’s most essential skill and most vital gift to her daughter.

As piece of writing, For Tamara is a remarkable achievement. It reads fast – the narrative is propulsive – but more importantly it is compelling in its wealth of information and the way it unites the before and the after. We never really find out how the world ended, but in the end it doesn’t really matter. As the narrator tells us, “I have this life of extraordinary memories,” and later, “I’ve never seen time as linear. / I get it, / but I don’t get why I can revisit any time I want.” The act of memory – its sheer plasticity – is on display in almost every line of the poem as the speaker flips from present to past, from memory to visceral reality. Only at the end do we get any clear sense of what might have happened: “The explosions were brilliant, blinding. / Then clouds. / We’ll never know.”

Part of the power of this poem is its enjambment of completely different types of rhetoric – the speed with which it switches between acknowledgment of the child’s innocence and limits of understanding (“I’m so proud of you”; “Your Dad loved you and me so much; he is sorry he can’t be here”; “Play nice.”) and a brutal truth telling (“Everything isn’t going to be fine.” “Tamara, you will watch me die. / This will be your responsibility.”). The use of punctuated line breaks within each line only heightens the tension of this enjambment. As in the opening pages, advice and commentary roll over one another, setting a furious pace, which Lang maintains for the rest of the poem:

“Basil is very temperamental. / I’m sorry, I have no idea how to make a TV. / Find a library, sweetheart, please. / Intact.

If all resources fail: bleach. / Learn to can / fruit, vegetables.

Flamingos, / to read, / that we love you. / Rhinoceroses. / Poplar trees have sunscreen (SPF15) on the south side.”

And later:

“You need songs. You can make your own. / I hope there are books. / I hope you find this one.

Learn to hunt. / Your Mum and Dad have been vegetarians, but never for the sake of your life. / Arrows and spearheads.

Then there are stories I can’t tell you. / Lying under a piano listening to Satie. / Yr Father lay under the piano / as a child in the park.

My Darling Dearest, first-aid kits are frivolous until you need one. / I’m sorry. / Eat strawberries (I dreamt about them last night.)”

What makes For Tamara unusual within the genre of post-apocalyptic visions is the way the normal interrupts the extreme, and not vice versa. Pop culture references appear again and again, both as references and as snippets of language – reminders of the casual idiom of a culture without concern for the bare essentials of survival. Her use of pop culture references are especially compelling: Doctor Who’s blue telephone box, lightsabers, the word “frak” in place of fuck (a clever homage to another of our culture’s great post-apocalyptic narratives: Battlestar Galactica). Where pop-culture references in other poet’s poems often feel frivolous or like hipper-than-thou accessories, something to show the poet is in-the-know, here they are markers of sadness: for what was lost and is recoverable only through memory, through reference.

What’s affirming about this is that, while the larger structures (and infrastructures) of society may have been wiped out, the social sense itself – that which binds humanity together in its most local form – has not. The narrator of For Tamara insists again and again that her daughter should love other people despite their faults; that not even the decimation of society erases the moral obligation to help others: “Don’t get angry with ppl for being human. / Just help; / and I know you can. / No use in screaming” she writes; and later: “Humans are gross and annoying. / Take care of them anyway.”

In terms of plot, For Tamara builds by degrees: we learn that Tamara’s mother has decided to turn her home into a school and hospital; we learn that her husband worked in some official capacity for the government and was somehow involved in the official response to the event (“We both knew his work was more important than us. Bigger than us”); we learn, in vague terms, that the event was caused by man. But what starts out fragmentary, out of focus, a landscape of random objects, resolved into focus with a macro lens, becomes a study of details from which we extrapolate an understanding of the larger world. Most of these details are the objects of survival; but in Lang’s poem, even memories are objects of purpose:

“I know this isn’t by the book. / But Darling, we’ve run out of those. / Trust your Mother. / This works. / I’m teaching you to make painkillers.”

It’s a smart move: by working with a multiplicity of possibilities (we don’t at first if the apocalypse came on the heels of disease or disaster, only the setting is definitely post-apocalyptic) all possibilities are open. By refusing to state clearly what happened, or how it happened, we are free of presumption; like everyone else, we are looking for knowledge. The absent husband is perhaps the most intriguing character of all. Through his absence, he becomes more present. While her affections and fierce devotion for Tamara’s father never wavers, her letters to him traverse the emotional spectrum; at one moment praising, at another pleading:

“Even though I’m the woman who loves you regardless: / call home./ Magic a way. / I don’t care. / T. is only going to get so many more stories.”

And later, scolding:

“You idiot. / You can’t figure out a way to contact us? / With everything you have access to?”

It’s a bit reminiscent of the absent parents in Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time – idealized yet flawed – and so loved their absence becomes painful even for the reader. By addressing the husband directly (“Husband of Mine” “My Beautiful Idiot”), Tamara’s mother creates a relationship with her husband for her daughter that enfolds in real time; her words give him presence. “Love someone for who they are,” she advises. “That was part of who he is / to deny him that would be cruel. / And yes, I miss you, Husband of Mine. / Every single fucking day.”

But even words have their limitations – and it is against these limitations that Lang battles and is the source of the poem’s ultimate tension. At one point, towards the end, Tamara’s mother writes: “I wish I could just sync our brains, / and give you everything in mine. / Then again if humans could do that / we wouldn’t be so human.” She maintains a relentless focus on what it means to be human; despite the destruction, the collapse of society, Tamara’s mother retains faith in humanity, in its absolute necessity.

Yet the world imposes its own rules; idealism exists side by side with reality, and the responsible mother protects not by hiding knowledge of the world, but by exposing. The effect of even simple statements like this are as necessary as they are heartbreaking: “Everything isn’t going to be fine,” she tells Tamara. “As much as I’d love to tell you otherwise, / it ain’t. / And you have to learn that sooner rather than later.”

Unlike most post-apocalyptic narratives, this is not a tale of endless, fruitless wandering – seeking the Eden that is no longer there (one is reminded of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road) but a tale of rebuilding civilization from scratch. Instead of running – if only to have the simulacra of progress – Tamara’s mother stays in place, turning the remains of her home into a hospital and a school. In a way, she follows the advice parents often give to their children: if you get lost, stay where you are. By maintaining place, she preserves hope: hope that she can build a future for her child; hope that her husband will come back and rejoin her; hope that by staying firmly put, the world will grow back in around her.