MATT SHANE‘s practice is split between painting, drawing and installation, while firmly embedded in the realm of landscape. His pictorial worlds assemble an array of influences: European Romantics, Chinese ink painters, the Hudson River School, the Group of Seven, science fiction, photojournalism, album art, comics and zines. He has done solo and collaborative exhibitions on three continents. His large-scale drawing environments are produced with collaborative partner Jim Holyoak, and often involve hundreds of participants.

Shane has received numerous grants and awards and done residencies at NKD Norway, Cuadro Dubai, Wander Den Haag, the Baie Saint Paul Symposium, Art Omi NY, KIAC Dawson, the Banff Centre and the Vermont Studio Centre. He received an MFA from Concordia University in 2013 in Montreal, where he currently lives and works.

B O D Y‘s Art Editor, Jessica Mensch, caught up with Shane recently to find out about his recent projects, and how landscape painting contributes to our understanding of the modern world.

B O D Y: You paint landscapes – from futuristic cityscapes nestled in throbbing organic environments to bucolic, impressionistic winter scapes. How did you come to landscape painting?

Matt Shane: I’ve probably been drawn to landscapes for as long as I’ve wanted to travel. When I was a kid I spent a lot of time looking at atlases and planning imaginary trips to the Caribbean. I wrote to a number of pen-pals in Grenada and St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and I’d learn about these islands through their stories. It was thrilling to read about a landscape that was so completely different from my own in Vancouver. I thought I would grow up and work on boats, but instead I became an artist, which has also allowed me to travel a lot.

I think mental transportation is the root appeal with landscapes. It’s similar to going to the movies, playing a video game or reading a novel in that it’s an immersion into a fictional world. But with landscapes, the central character is a place.

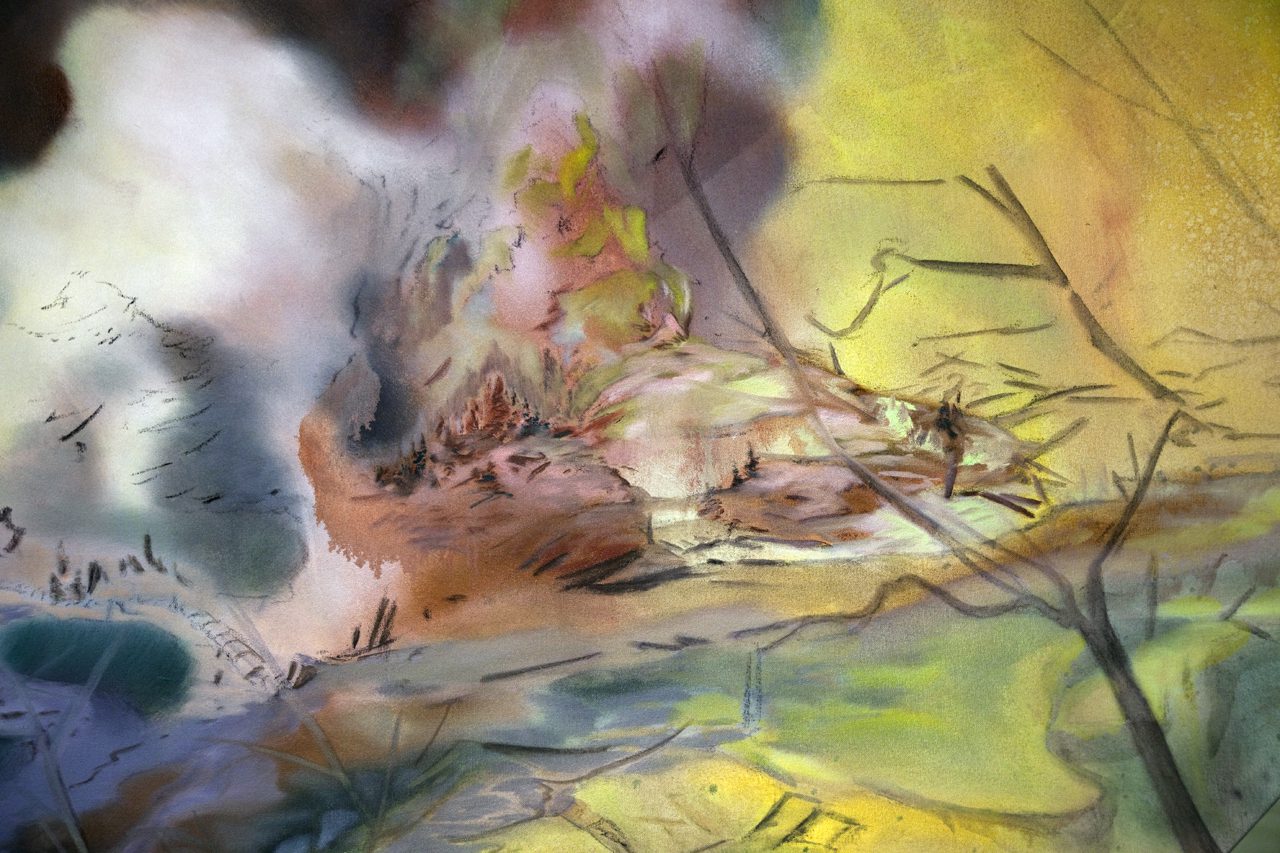

We feel a heightened sensitivity when exploring places we’re unfamiliar with. Our patterns of behavior are thrown off and we’re more open to diversion and discovery. For that reason, I like painting ambiguous places, somewhere at the border of geography and imagination.

B O D Y: With place playing the central character in your story, does this explain why your cities and rural homes etc. are often dwarfed by their natural surroundings?

Matt Shane: At some level, all landscapes are distorted representations of nature, and the distortions are often overt in my paintings. Like you say, sometimes the natural elements dwarf the architecture, or else cities overwhelm the landscape. These scale shifts speak to a mutable perception of humans and our effects with regards to the natural world.

We have a confusing relationship with nature. We are, or course, animals interacting with our environments, and yet we define nature in opposition to ourselves. We are in this strange position of being within and without at the same time.

B O D Y: One of my favorite paintings of yours depicts buildings collapsing. How do you place this narrative in the context of your other works where the natural landscape takes on a decisively chaotic and explosive character?

Matt Shane: That painting is part of a series of ‘sketches’ I was doing of what I perceived to be disaster sites.

Normally, I paint from a collection of images, collaging elements together on the canvas until a landscape sort of emerges. The disaster sketches were done differently. They were painted quickly from a single image source with altered colours. With that collapsing building painting, I was interested in the motion and changing state of the architecture. It goes from something fixed and solid (concrete) to something more like liquid or gas. It seems to dissolve. And paint is an interesting medium to represent state changes because it is active and unstable itself.

B O D Y: So it’s natures constant state of transmutation that attracts you?

Matt Shane: Yes. We often try to halt changes and to stabilize our environment, but nature can’t be fixed. It is always changing, and there is an inherent sense of possibility in that knowledge.

B O D Y: You recently finished a residency in Dubai – where the hyper current city and its surrounding dessert landscape appear to make for an unusual relationship.

Matt Shane: Definitely a strange relationship. In Dubai, there is a stark contrast between the vertical city, and its vast desert and ocean surroundings. The city’s landforms are quite surreal. Rivers, lagoons and clustered islands are observably man-made, and for that reason one is tempted to call the whole city ‘artificial,’ even though, in a way, every city is artificial. Dubai takes a defiant sort of pride in its spaceship-like qualities. It prefers extravagance and abundance over environmental integration.

Dubai has grown so quickly over the last 20 years, and its identity is tied to a vision of newness and progress. I couldn’t help but think of how things would age. Robert Hughes said ‘nothing dates faster than people’s fantasies about the future.’ I would look at these incredible towers, malls, hotels, and gardens and think about what they would look like in 20, 50 or 200 years. What will happen if the economy can no longer sustain the wealth of workers, who keep things so clean and well-maintained? Without air conditioning, I could imagine structures melting into the sand.

B O D Y: Most of your work from this period was of the city. What was it like for you to look out across the comparatively empty desert?

Matt Shane: It’s quite flat around the city, so it’s hard to get an idea of the scope of the desert. There is a huge dune park full of white SUVs and dune buggies pulling crazy moves. I took special interest in a few massive construction sites fringing the city. After the 2009 economic collapse, many developments were put on hold, and they remain so today. There are acres of dredged-out pits, hills, walkways, and skeletal concrete structures with uncertain futures. They are construction/destruction sites. I wondered if, with time, more of the city could look like that, or would the economy bounce back and real estate start to boom again. It seems as though that’s what’s happening now. Dubai is surprisingly resilient.

B O D Y: I can imagine it as a time-lapse montage: a city in a constant state of transformation – from looking new, to looking old, to looking new, to looking old, etc.

Matt Shane: Yeah, well, that comes back around to what we were saying about nature being constantly in a state of flux. Cities are subject to the same natural forces as everything else. They change and evolve just as their surroundings do.

B O D Y: In an earlier conversation we had off-the-record, you mentioned you were interested in presenting your large-scale paintings as elements of a set in more immersive three-dimensional environment…

Matt Shane: That is my project for this fall. I want to experiment with the space around the painting. I’d like to make a landscape, which is both pictorial, and three-dimensional. Something you can look at as a painting, and also walk through. I have yet to determine the mechanics of it, but I’m excited to try something completely different.

— Jessica Mensch