THE UNFINISHED LIFE OF PHOEBE HICKS

(selected excerpts)

The Victorian period was not only a haunted age; it was also, in every sense of the word, a hallucinatory age, lending itself to every type of illusion, even at the level of bricks and mortar. The Victorian house, the Victorian street, encouraged illusion and hallucination, the Victorian theatre was a hotbed of optical tricks, only the kitchen escaped the obsession with the manufacture of articles which appeared to be something else: money-boxes disguised as books, substantial-looking doors that on examination was merely cunning paintwork, solid-looking chairs that were, in fact, featherlight, being manufactured from papier-mâché. Nineteenth-century man and woman were disposed to believe […] that things were not as they seemed. Their senses had a habit of letting them down, and they were mentally prepared for any odd happenings, fugitive visions, the unaccountable thing seen out of the corner of the eye, the strange sounds in the middle of the night, the tap on the shoulder that might be a visitation from another world.

Ronald Pearsall, The Table-Rappers: The Victorians and the Occult

Nostalgia

It was the year when a vague, indefinable restlessness seized the inhabitants of Providence and gnawed at their souls. They were plagued mid-century—as in the first half—by a damp and sweltering August. The mosquitoes, exceptionally annoying that summer, made the empty streets after sundown feel all the more deserted. Their high-pitched whine and from time to time the distant wail of a child trapped in some baking room, reverberated in the air. The lucky few had left in time for the ocean: for Little Compton or the islands of Nantucket and Block Island. There the early mornings and evenings brought fresher gusts of wind and the fish lying on ice-covered tables in the harbour, caught only moments before, whetted something resembling an appetite. Yet even in Little Compton it was hard to walk down the cobbled streets in the middle of the day. There was nothing to do except sit on the shore in a wicker strand-chair with one’s back to the sun and count on the barely perceptible sea-breeze, or seek in a darkened room answers to the same questions tormenting the inhabitants of Providence who had remained in town.

Like the rest of humanity, the citizens of Providence would have gladly devoted themselves to some useful occupation—the women happily spending sultry evenings crocheting doilies, the men proudly organizing hunting parties. That summer, however, even such simple pursuits filled them with nostalgia. After their death, what would become of the snow-white napkins painstakingly folded and stored in cavernous chests? Who would dust the antlers sticking out at such a curious angle over the fireplace?

Such questions tormented the citizens of Providence struggling in summer to catch their breath and strolling in autumn beneath the famous New England maples, whose colours changed through over thirty shades of scarlet and pink. Thank God the inhabitants of the harbour town didn’t have to dwell on such dismal thoughts in the long winter dragging on mercilessly from December to April. The problem resolved itself earlier: in November 1847.

The Time was Ripe for Spiritualist Séances

Half a century meanwhile was passing into oblivion, bearing away with it long-haired heroines despairing on Romantic canvases. What its second half would bring remained an enigma to minds exhausted by a strange anxiety. At the end of October no one suspected the time was ripe for Spiritualist séances.

[…]

The Schedule of Séances

On 2nd December 1847 Phoebe Hicks conducted her first séance—still tentative, in a room not entirely blacked-out, with the participation of not the most aptly chosen guests, who proved to be more a hindrance than a help. A second séance followed, however, already more accomplished, and then a third, even more successful. And as to subsequent ones…

During the fourth one, guided by an internal impulse, Phoebe introduced a rule observed afterwards by her successors that séances should always be held at the same hour and in the same room. She sensed instinctively that spirits were attached even more than mortals to particular places (hence the ghosts of former inhabitants harassing the old houses), And that the stale aura prevailing beyond the grave made them value well-ventilated chambers. Levitating mediums would take advantage of this knowledge and even in late autumn leave open a parlour window. To the astonishment of the assembled participants, they could then fly out of it and back in at will.

Phoebe’s séances—like those of mediums that came after her—took place at round or oval tables supported by a sculpted leg (replaced later by frauds with smaller tables on wheels). Starting from the fifth séance, Phoebe invited an uneven number of guests. The ideal group, she believed, consisted of four gentlemen and four ladies including the medium. Phantoms apparently favoured clear divisions. If there were more participants, they never exceeded a total of twelve. The erotic charge emitted by touching palms, knees and feet conferred an additional earthly quality on the meetings of Spiritualists of both sexes, who on the medium’s request always sat alternately: woman, man, woman, man. A salute of respect to visitors from the Beyond was the rule that no séance should last for more than two hours. Spirits, according to Phoebe, were endowed with less patience than mortals. Their behaviour could be just as unpredictable as that of the magic town’s inhabitants. Now and again they appeared with some object in their hands that had originated in their former stay on earth, as though their families weren’t otherwise capable of recognizing with whom they were dealing. Other times they’d make their presence felt only by a smell, light, or a kind of foreboding suddenly descending upon one of the guests.

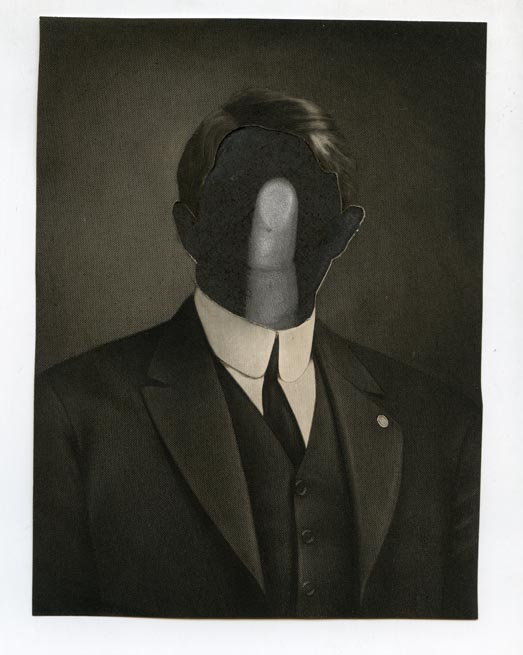

Phoebe’s fame spread swiftly across New England. Her séances were the talk of five-o’clock teas, whispered over during too long Sunday services or evening strolls amid colonial houses. Dockhands shouted to one another about them in the ports. Those who’d taken part for the first time would relate endlessly how the heads bent over the table seemed so lonely—as if suspended in the air around the gleam of light shed by the oil lamp, liberated from constraining hands, legs, bellies, throats and backs of necks. Free yet incomplete, hardly begun. Because of the impression they’d been guillotined seeming to belong more to the world of the dead than the living. Reminiscent of Catholic saints in the moment before martyrdom: staring eyes, half-open lips, a glimmer behind in the shape of a halo. Some people compared the collected face of the medium, as if amputated and set against the dark background, to a blob of ectoplasm.

Phoebe marvelled at the attention devoted to her by the newspapers. She had no time to reflect, however, upon the strange mechanisms of fame—so many new responsibilities rested upon her. Though she preferred to entertain guests in her own home, some invitations she could not refuse. So if on Monday she was to take part in a séance at the house of Mr and Mrs B., her neighbours on Benefit Street, then she knew that on Tuesday she would have to accept the invitation of their relative Mr C., fortunately also residing nearby like everyone else in Providence—which in turn entailed the necessity of conjuring up, on Wednesday, the spirit of the prematurely deceased brother of Miss K., a spinster living out her days in solitude in the neglected family mansion. And though the elaborate iron fencing and widow’s walk, grander than any other in the neighbourhood, still recalled their former glory, the house’s location entirely harmonized with the melancholy of its owner. The windows overlooking St John’s Cemetery conferred upon the séances an atmosphere Phoebe did not like. Her ease in establishing contact with spirits was not at all accompanied by the pleasure some folk derive from the tranquillity of cemetery alleyways.

The Mosquito

Phoebe Hicks’s first trance was interrupted by a mosquito. No one knew how it flew into the darkened room, drunk on human blood, since the windows were shut, heavy blinds drawn—and for mosquitoes it was too late in the year. Witnesses to this historic event claimed later that it was not of this world, that the spirit of a local pastor conjured up earlier had materialized in it. They maintained that Phoebe had not heard the pastor out, so he’d returned in the form of an insect to prevent other spirits from telling their stories. Although this theory seems to have been a hoax, many mediums afterwards feared insects’ buzzing would ruin their concentration.

Who was Phoebe Hicks?

When Phoebe Hicks conducted her first séance, when she became the first medium in New England, when her fame began to entice other women to embark on a similar career, no one foresaw, of course, what would distinguish her from her successors. This difference, not so crucial at first glance, fundamentally influenced Phoebe’s story. Thanks to her good birth into a well-to-do home on Benefit Street, Phoebe Hicks enjoyed a financial independence rarely accessible to women in those days. As fate would have it, her parents died—poisoned by crab meat, according to rumour—leaving a fortune she did not have to share with non-existent siblings or cousins. At the age of thirty-three, the unmarried Phoebe knew her future was secure and life would drift on as in an uncapsizable boat lined with down. Few mediums could afford to reject marriage, which Spiritualism saw as the main source of restrictions on women’s freedom. Phoebe Hicks along with Achsa White Sprague, who would be miraculously cured from a longstanding debilitating illness and famous for her public speeches uttered in trance, belong to that small group of female Spiritualists deaf to the declarations of wealthy suitors.

The spirits invoked by Phoebe, materializations and levitations were the product of boredom, a sense of theatre or of actual contacts with the Beyond. Séances brought her amusement, local renown, the interest of newspapers, admiration of many ladies and gentlemen, disapproval of conservative citizens, but no profit measurable in monetary terms or improvement in social status. Thus she sometimes allowed herself extravagances without caring what her guests would say. The phantoms she conjured caused bewilderment among the Spiritualists sitting motionless in the dark rather than answered their questions.

Her successors, who came from modest families and treated Spiritualism as a path to social advancement, could not afford such luxury. They could not refuse—as Phoebe did— invitations to participate in public trances organized in town halls hundreds of miles apart. Such spectacles brought financial gain, satisfaction (these were the first public speeches delivered by women) but also the risk of humiliation by audiences. And though in the eyes of many critics of the new fashion accepting a fee was evidence of fraud, the majority of mediums were unable to turn it down. Exhausting journeys and the abuse of alcohol, intended to enhance their visions, were the daily bread of thousands of women whose vocation of “medium” found its way into the official list of American professions only a few years after Phoebe Hicks consumed stale clam.

Phoebe meanwhile wished to hear neither of public performances nor excursions away from the magic town of Providence. She selected carefully the participants in her gatherings. Accounts of the goings-on in her house exceeded in folly and imagination descriptions of other séances, conducted with the expectations of wealthy benefactors in mind.

And though malicious folk whispered that the success of her séances depended on the paucity of other attractions in the town of Providence, it’s not worth paying heed to wicked tongues.

[…]

The Spirit of Leonora de la Cruz

Of the figures drawn by Phoebe from the Beyond, several were literary. The Spanish visionary nun, who slept through a large portion of her life dreaming prophetic dreams and was known in the nineteenth century only to a few bookworms, manifested herself in all her glory during a certain September séance. She began by driving out once and for all the spirit of the fair but gruesome Elizabeth, Countess Báthory, atoning beyond the grave for the murder of hundreds of young women in whose blood she had bathed to preserve her beauty. Initially, Phoebe’s consternation was aroused by the rare event of a squabble between phantoms. On closer inspection of the victorious phantasm, the medium’s astonishment mounted when she saw its likeness to herself! Phoebe knew many Spiritualists would find in this coincidence endorsement of the rumours about her dishonest practices. All the more rapidly therefore, she let go the hand of the pastor sitting next to her and turned up the lamp flame. In its light the assembled guests observed the sisterly likeness even more distinctly. They also satisfied themselves their hostess still occupied the place of honour at the table. Even the most ardent sceptics ruled out her incarnation in a ghost. Hardly had the phantom materialized sufficiently for the Carmelite habit and pilgrim’s shell from Santiago de Compostela held in its hand to become visible, when, without waiting for questions, it began to enumerate in a monotonous voice the various catastrophes awaiting the twentieth century. The sinking of the “Titanic,” the “Hindenburg” disaster and several other tragedies, about which neither the medium nor her guests wished to hear. And so for the first and last time in her mediumistic career Phoebe interrupted the visionary mid-stream, and sent her back to the Other World. The sitters heaved a sigh of relief. Only at their next meeting did the well-read Emily Brown recall the heroine of a justly forgotten eighteenth-century French novel of unknown provenance, Leonora de la Cruz. The medium’s amazement that a fictional figure could look like a twin sister, knew no bounds!

____________________________________________________________________

AGNIESZKA TABORSKA (b. 1961) is reimagining the surreal for the postmodern era. A lecturer at the Rhode Island School of Design since 1989, her main areas of interest are the image of women in fin de siècle Western art and literature, French Surrealism, the significance of women in the movement, and the impact Surrealism has on contemporary art. Her literary collaborations with American collage artist Selena Kimball are contemporary experiments in Surrealism. The Dreaming Life of Leonora de la Cruz (tr. Danusia Stok, Midmarch Arts Press, 2007) and their next book, The Unfinished Life of Phoebe Hicks (tr. Ursula Phillips) join image and text in parallel narratives. She has produced RISD annual Cabarets (1992-1997). She has taught at the Pont-Aven School of Contemporary Art, Pont-Aven, France (1996-2004). She has curated exhibitions of Surrealist art in France and Poland and written scripts for documentary films related to Surrealism. She is the author of 13 books published in Poland, the United States, France, Germany, Japan, and Korea. Her works of fiction have received literary prizes in Germany and have been adapted for stage and brought to screen in the form of award-winning animated films at international film festivals. Excerpts from her book The Unfinished Life of Phoebe Hicks have been published in The Saint Ann’s Review. Her other books include Conspirators of Imagination, Surrealism (a collection of essays published in Poland), The Whale, or Objective Chance and Not as in Paradise (the latter two collections of short stories published in Poland).

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

URSULA PHILLIPS lives and works in London, and is a scholar and translator of literature by Polish women authors. She has recently published translations of Maria (Czartoryska) Wirtemberska’s Malwina, or the Heart’s Intuition (Northern Illinois University Press, 2012), the first widely recognized novel by a Polish woman, and Narycza Żmichowska’s The Heathern (Northern Illinois University Press, 2012). With Polish scholar Grażyna Borkowska, she has published Alienated Women: A Study on Polish Women’s Fiction 1845-1918 (Central European University Press, 2001), and with Borkowska and Małgorzata Czermińska, Pisarki polskie od średniowiecza do współczesności: przewodnik (Polish Women Writers from the Middle Ages to the Present: A Guidebook, słowo/obraz terytoria, 2000).

____________________________________________________________________

About the Artist:

SELENA KIMBALL is a visual artist who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Her emphasis is collage but she also works in painting, photography, and film. She has exhibited in museums and galleries in the US, Mexico, France, Poland, and Romania. The collage novel she coauthored with Agnieszka Taborska, The Dreaming Life of Leonora de la Cruz, was published in Poland, France and the States. She lives in New York and teaches at Parsons The New School for Design. Her website is selenakimball.com

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Agnieszka Taborska:

Short stories in The Brooklyn Rail

Agnieszka Taborska’s page at The Polish Cultural Institute