NATURA MORTA

(selected excerpts)

White peaches, red broom, pomegranates tumbling down the escalator steps: with these delicately rendered details, Josef Winkler’s ‘Natura Morta’ begins. In Stazione Termini in Rome, Piccoletto, the beautiful black-haired boy whose long eyelashes graze his freckle-studded cheeks, steps onto the metro and heads toward his job at a fish stand in Piazza Vittorio Emanuele. In awarding this book with the 2001 Alfred Döblin Prize, Günter Grass singled out Winkler’s commitment to the writer’s vocation and praised ‘Natura Morta’ as a work of dense poetic rigor.

White peaches, red broom, pomegranates tumbling down the escalator steps: with these delicately rendered details, Josef Winkler’s ‘Natura Morta’ begins. In Stazione Termini in Rome, Piccoletto, the beautiful black-haired boy whose long eyelashes graze his freckle-studded cheeks, steps onto the metro and heads toward his job at a fish stand in Piazza Vittorio Emanuele. In awarding this book with the 2001 Alfred Döblin Prize, Günter Grass singled out Winkler’s commitment to the writer’s vocation and praised ‘Natura Morta’ as a work of dense poetic rigor.

A LITTLE HUMPBACKED MAN with a waxen face, his cadaverous skin covered in black blotches, crossed himself and kissed the black fingertips of his emaciated hand, while a group of nodding bishops dressed in red, wiping the sweat from their chins with kerchiefs embroidered with yellow mitres, walked past him through Saint Peter’s Square. His eyelids and eyelashes were painted black with mascara, his eyes were yellowish and blood-spotted, his sparse hair was dyed black, his moustache flecked with gray. Wheezing, he pulled his mouth open and closed and grasped his throat with a hand covered in golden rings. Passing pilgrims sneered in disgust and whispered to one another, “Sida.” “Pantaloni lunghi! diecimila lire! pantaloni lunghi!” called out the woman selling the paper pants with the word Roma printed in green, rubbing together two Vatican coins, while the guide of a group of young people walked by with a yellow flag on which a pietà was painted. On the breast of their identical white T-shirts in green letters stood the word Jesus, and on the back, wine-red, Alleluia.

A dog on its hind legs with a protuberant member snapped over and over at the small crucifix hanging from the wrist of an exhausted woman leaning with her eyes closed against the wall. A kneeling girl bumped her forearm against the thigh of a young monk holding a clear plastic bag of freshly washed cherries. Water droplets clung to the fruits and glinted in the interior of the plastic bag. Two girls wrote down their names and phone numbers between drawings of pierced hearts on paper pants and passed them to two giggling boys who had pulled off their shorts and tugged the long embellished paper pants with the green motto Roma over their naked legs. Furtively, with a contemptuous glance at his slowing step, a pair of teenagers watched the small, humpbacked man blow curdled black blood into his kerchief, and bright blood drops fell onto his right forearm. A girl wearing shimmering blue sunglasses in bile-green frames shrieked, to the amusement and dismay of her entourage, “Last stop!” A mother was speaking Spanish to her adolescent son, who sported a whiff of blonde beard; when she saw the sick man, she laid her arm over her son’s shoulder, and afterward let it glide slowly over his back and right buttock; continuing on with the boy, she slid the hand on his right buttock hastily into his jeans pocket. The eyes of peacock feathers were embroidered down the seams of her long gown, its edge dangling just over the asphalt.

Watching the small, humpbacked man coughing and spitting up blood, his waxen countenance corpse-yellow, his skin covered in black blotches, a black-clothed nun pulled a rosary from a leather case and kissed one of its black joints. The fig vendor’s son with the long black eyelashes left Saint Peter’s Square accompanied by the blonde girl in the short-sleeved white T-shirt with the wine-red camels and the sand-colored pyramids, chewing on the silver cross around his neck and toying with the plastic pacifier dangling from his right wrist, ten meters or so behind the back of his mother, who called out “Fichi freschi! vuole fichi! fichi freschi!” and behind his little brother counting the big, limp fig leaves, along the Via di Porta Angelica in the direction of the Piazzale Risorgimento. The clean-shorn man of fifty in the white T-shirt printed with the phrase Mafia. Made in Italy, beat his Moor’s head staff with the swollen red lips against the placard that portrayed a masked child, his legs shackled, sitting in an electric chair, and shrieked “Mamma! Mamma!” over and over, scowling and rubbing the other hand on his genitals. Vanished was the human torso with the shimmering reddish shoulder-length hair. The wind wafted a few pages of the L’Osservatore romano from the middle of the street to the street’s edge. The fig vendor’s son with the long black lashes and the blonde girl went together in a green circolare to the Piazzale del Risorgimento and headed in the direction of the Villa Borghese.

[. . .]

HOLDING TWO NERVOUS GREYHOUNDS by the leash, a woman, accompanied by a child carrying stiff black X-ray sheets in a see-through plastic bag, walked through the fish and butcher stands to the fruit stand and bought a kilo of plump white peaches. Sluggishly she kept opening her eyelids, smeared with thick black mascara. Not even her teeth were spared her red lipstick. Two Moroccan adolescents walked down between the peach and apricot stalls to where the honeydew melons were sold, each resting his arm on the other’s shoulder, pressed their cheeks flirtatiously together and glanced back, laughing, at a man surreptitiously trailing them. An old, one-eyed Moroccan with a frizzy gray beard, selling socks, underwear, sunglasses and alarm clocks between the fruit stalls, was eating a honeydew melon. The honeydew melons were packed in wood crates over wood shavings. A fern leaf covered up by a piece of see-through plastic lay over a redolent, sliced-open honeydew melon. The melon vendor pinched the wandering son of the fig vendor, who showed up now here, now there, on his broad backside and shouted, flirtatious and insistent, “Allora!”

By a mound of green pistachios lay a bouquet of roses, on a hill of dry black plums and various red and pink paper roses. A barefoot gypsy girl with matted, stringy hair, eating cherries from a paper sack and spitting the pits out at her feet, hawked swimsuits and boxer shorts, shouting “Mille Lire!” to the fruit vendors and passersby. Piccoletto peeled a banana, threw the yellow skin on the ground, and held the slick, white, slightly bowed fruit in his hand, sucking at it a moment before eating it one bit at a time and squashing the pieces with relish between his tongue and gums. After he had finished the banana, he wearily rested his head against a wooden crate of strawberries. In a clear plastic bag carried by a negress, a transparent baby bottle, half-full of milk, was streaked with the remains of a banana. A banana skin in her hand, a young German tourist stood helpless and indecisive before the discarded vegetables and fruits before bending over and delicately placing the banana skin on the waste pile.

The female lemon vendor threw several crates of moldy lemons out on the side of the road. An old woman gathered the yellow netting from the lemons cast about, separating it from the rotting and moldy lemons and stuffing it in a plastic bag. The toothless lemon salesman pressed a microphone-like device into his neck, from which one could hear, in a soft, computer-like voice, “Limoni! limoni! mille lire! limoni!” A customer showed the female lemon vendor, one of whose eyelids twitched incessantly, a photo taken on the occasion of her fortieth wedding anniversary, in which she and her husband — he in tails, she in a white dress — stood on the steps of a church. “Bello!” the lemon vendor exclaimed with delight, “molto bello! complimenti! complimenti!” In a bowl garnished with tropical fruits, among dried pineapples, dates, and figs, lay a doll of the Christ child with outspread arms and a gilded wire halo. A small blond gypsy child suffering from acute alopecia, his scalp crusted with filth, walked barefoot among the glass cases, viscera, bloody chicken heads and yellow chicken feet toward the fig vendor. A gypsy girl peeled a fresh green fig with her long and filthy red-lacquered fingernails. With a fake ponytail that had fallen from her head, she spanked her small, whining child, who was gnawing at the peeled fig, on the behind.

A weeping boy, left alone among the crowd, wore a T-shirt printed with a road sign bearing the image of two dogs and the legend Attenti al cane! “Lascialo in pace!” said the pineapple vendor, sharp and determined, his expression completely stiff, when Piccoletto asked him who was the boy whose gilded, holographic visage hung from a golden chain around his neck, his eyes closed or open depending on the pineapple vendor’s movements. Piccoletto rested a wooden crate full of fresh green figs on his hips, while his mother shopped for sage, rughetta, and basil, and laid a bundle of parsley in the fig crate under her child’s navel, grazing his exposed belly. While the gypsy woman held a garment in the air, offering it to the pineapple vendor, her teat slid from the mouth of her child, who squealed in hunger. The gypsy shoved her nipple, stiff and dripping milk, back between her child’s lips, his mouth filthy and his eyes sealed shut with pus.

This excerpt has been published by permission of Contra Mundum Press. Josef Winkler, ‘Natura Morta: A Roman Novella‘ (New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2014).

____________________________________________________________________

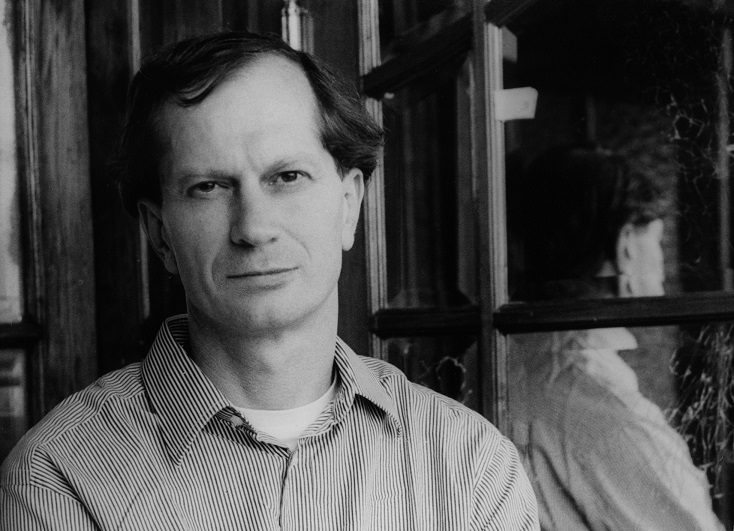

JOSEF WINKLER is the author of nearly twenty books, among them the award-winning trilogy Das wilde Kärnten. His major themes are suicide, homosexuality, and the corrosive influence of Catholicism and Nazism in Austrian country life. Winner of the 2008 Büchner prize and current president of the Austrian Arts Senate, Winkler lives in Klagenfurt with his wife & two children.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

ADRIAN WEST is a writer and literary translator from the western Romance languages and German. His work has appeared in numerous journals in print & online, including McSweeney’s, the Brooklyn Rail, Words Without Borders, and 3:AM. He lives with the cinema critic Beatriz Leal Riesco.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Josef Winkler:

Excerpts from Graveyard of Bitter Oranges in The Paris Review

When the Time Comes serialized in The Brooklyn Rail

Selections from Natura Morta in Asymptote

An essay by Adrian West on Josef Winkler in Asymptote

From Domra, On the Shore of the Ganges in FWRICTION : REVIEW