Einstein on the Beach: An Opera in Four Acts

Directed by Robert Wilson

Music & Lyrics by Philip Glass

Choreography by Lucinda Childs

Should you bring a sandwich to Einstein on the Beach? In a theatre in Paris in the throes of the four-and-a-half-hour opera, this is the question that drifts over on a smoked-salmon-scented breeze from the couple seated to the right. She wears the sort of effortless chignon that women in Brooklyn study YouTube videos to perfect; he sports glasses on loan from Gregory Peck circa To Kill a Mockingbird; and the sandwiches come out promptly during the second “Knee Play,” or intermezzo, as if rehearsed. It’s a little reward, a first-hour benchmark, and it’s both impossibly crass and inarguably practical.

Einstein, of course, is the interminably long, bafflingly opaque, glacially paced 1976 collaboration between the avant-garde theatre director Robert Wilson and the composer Philip Glass. Its latest revival completes an international tour in Berlin early next month. Paris, where I saw the production in January, loves Wilson: with a recent residency at the Louvre and a festival in his honor at the Théâtre du Chatelet, the Waco, Texas native has consistently found support in French producers and audiences. In what Americans find unmarketable and interminable, of course, the French see a certain je ne sais quoi. So it’s a bit of a surprise when, halfway through the production, the audience starts dropping like flies. We need a guide to Einstein, translated into as many languages as there are stops on its tour. Should you bring a sandwich? Should you take a nap? Should you strain to make interpretations, or just kick back and try to have a good time? The audience needs to know. What’s the best way to watch — to appreciate, even to enjoy — Einstein on the Beach?

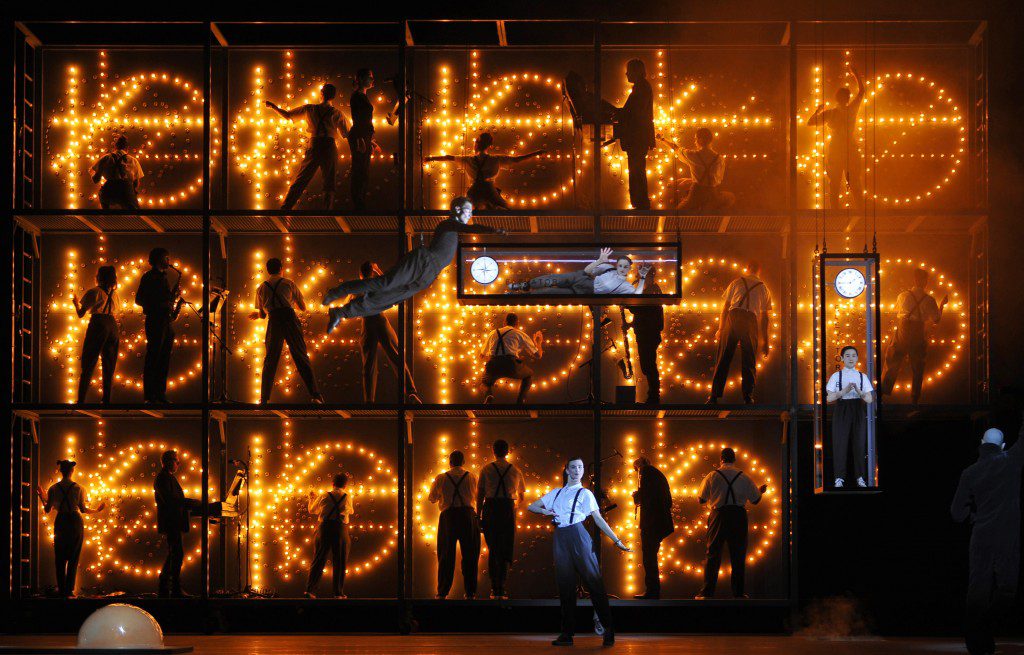

In lieu of any comprehensible narrative, Einstein is bound by its structure. The opera is composed of a series of nine twenty-minute scenes, broken into four acts, bookended by five “knee plays,” the “joints” of the performance. It is performed without an intermission. A landmark production in the “Theatre of Images,” the “opera” flits between spoken monologue and Glass’s arrangements, set against the backdrop of protracted physical movement and Lucinda Childs’ minimalist choreography.

Wilson’s theatre echoes, if you want it to, the work and ideas of Donald Judd, André Breton, Gertrude Stein, Richard Foreman, Merce Cunningham and Martin Heidegger, among others. But Einstein’s greatest influences were two children: the 11-year-old Raymond Andrews, deaf and mute, and Christopher Knowles, now a well-known poet, who was born with brain damage and who first met Wilson at the age of thirteen. In a 1985 documentary produced by the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Wilson recalls asking Knowles if the young man knew who Einstein was. Knowles’ response became one of Einstein’s several perplexing monologues, repeated and re-repeated and contorted and distorted over the course of the production:

Would it get some wind for the sailboat. And it could get for it is.

It could get the railroad for these workers. And it could be where it is.

It could Frankie it could be Frankie it could be very fresh and clean.

It could be a balloon.

The text that accompanies Glass’s music is similarly non-expository. Although he is affiliated with the minimalist movement, Glass prefers to be called a composer of “music with repetitive structures.” In “Knee Play One,” one of the best-known compositions in the opera, a choir chants over and over with minimal variation: one two three four, one two three four five six, one two three four five six seven eight. In “Knee Play Three,” the counting becomes supercharged — onetwothreefouronetwothreefouronetwothreefouronetwothreefour — jittering ecstatically like the soundtrack to an Atari game. In “Knee Play Four,” they sing scales.

Repetition is Einstein’s refrain. For nearly an hour, one of the dancers walks back and forth across the stage in a single diagonal line (the “Diagonal Dance”) until the audience nearly collapses of empathetic exhaustion. Later, we’re treated to the delivery of this curious, droll monologue a staggering thirty-five times in a row:

I was in this prematurely air-conditioned supermarket and there were all these aisles, and there were all these bathing caps that you could buy which had these kind of Fourth of July plumes on them, and they were red and yellow and blue, and I wasn’t tempted to buy one, but I was reminded of the fact that I had been avoiding the beach.

Thirty-five is a lot of repetitions, but there’s nothing rote about this performance, which manages to emphasize something new each time around. If simply entrancing the audience were the intended effect, no doubt Wilson could have shaved an hour or two off the production — one’s eyes and ears and all other organs would glaze over seeing and hearing the same elements over and over and over again. But Einstein’s repetitions warp and evolve, and there’s no “getting the point.” One is reminded of Gertrude Stein, that other Great Frustrator, who was also known to say things more than once. “There can be no repetition because the essence of that expression is insistence,” Stein wrote, “and if you insist you must each time use emphasis and if you use emphasis it is not possible while anybody is alive that they should use exactly the same emphasis.”

Wilson’s appropriations of Knowles’s baffling language invite the audience to transcend the border between speech and sound, over and over and back and forth, insatiably. The director’s commitment to learning Knowles’ and Andrews’ (largely nonverbal) languages is on display in Einstein; the characters indeed communicate verbally, but each subverts and supersedes the limitations of linguistic content. Layer upon layer, content morphs into sound; sound accumulates, and then releases, its meaning.

“Mesmerizing,” “dreamlike,” and “trance-inducing” are a few of the go-to phrases Anglophone critics employ when writing about the experience of Einstein. But hardly anyone resists suggesting that the production itself is a sort of endurance test. “I am still not convinced that Einstein on the Beach would lose any of its mystical allure, vitality and wonderment if it were trimmed a bit,” writes the New York Times’s Anthony Thommasini. “Maybe more than a bit.” Rupert Christiansen in The Daily Telegraph is less reserved, calling the production “asphyxiatingly tedious.” Theatre, of course, is the only art form in which the “greats” can be chided for taking their sweet time. One is hard-pressed to imagine a McInerny or a Kakutani suggesting Melville might have trimmed some of the fat off of Moby Dick, or proposing that a few of the serialized portions of Ulysses ought to have been left on the cutting room floor. Likewise, what film critic would dare suggest that The Godfather would have been improved if only Brando had picked up the pace. And still it is a truth universally acknowledged that theatre ought to cut to the chase. It’s the reverse of the old joke in Annie Hall -— the food is terrible, and such small portions! — that the very best play is made even better by being over and done with. Cunningham and Cage are dead; the American theatre is now the champion of the ninety-minute one-act, and it’s about time.

Which brings us back to Paris, Wilson’s home away from home. Should you bring a sandwich to Einstein on the Beach? You’ll most likely get hungry. At four-and-a-half hours, you’re also likely to get thirsty, and stiff, and to notice a little swelling around the feet and ankles. The couple with the salmon has thought all of this through. No doubt they’ve got a thermos of coffee to go along with those sandwiches, and probably a change of socks, inflatable neck pillows, liquid tears and travel Scrabble, just in case. For the latter acts, they probably have something to support the lumbar spine and those toothbrushes that come with the paste already caked on the bristles. If Skymall had an “experimental opera” page, they’d own every item. To remain entertained. To stay engaged. To keep awake. To make it a little more bearable. They could do this all day. They could sit through anything! Einstein, Wagner, Robert LePage! Paul Thomas Anderson, oeuvres complètes! Every transatlantic flight, every hour of C-SPAN, every trip to the DMV!

But could they do better? As Craig Owens writes, Einstein calls attention to the poverty of language, “but also all processes of logical thought according to which we parse, analyze, literally come to terms with experience.” The deaf perceive differently from the hearing, just as the handicapped do from the whole, as Wilson does from Wagner, Cunningham from Coppola. Suspended in time and space, the protracted actions of Einstein’s characters and their emotional distance from the audience beseech us to confront our processes of perception using a language unique to the experience. At the end of the four-and-a-half hours in Paris, those who remain leap to their feet. They holler and cheer, ostensibly for Wilson, Glass, and Childs, who join the cast for a curtain call, but also for themselves, for having endured it. They did it! They made it! They’ve won — if only playing by the rules of a very different game.

–Morgan Childs