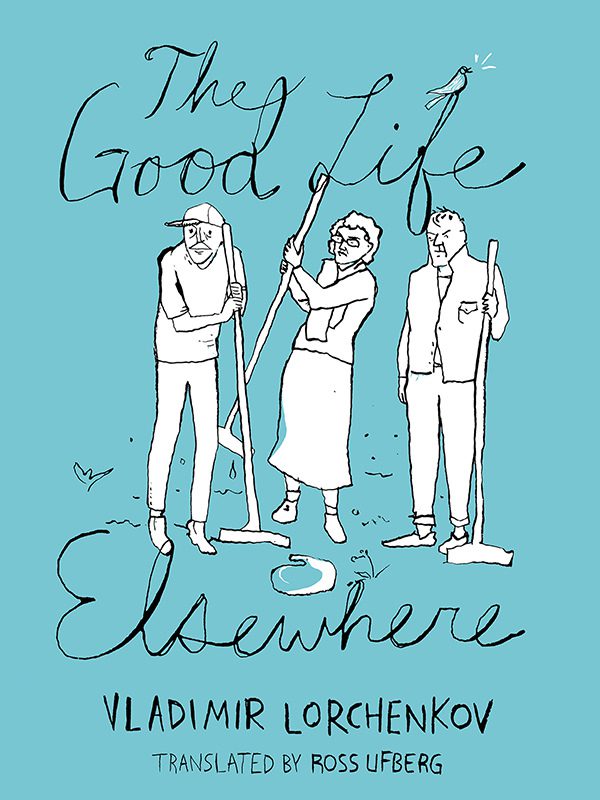

THE GOOD LIFE ELSEWHERE

(an excerpt)

Moldovan writer Vladimir Lorchenkov tells the story of a group of villagers and their tragicomic efforts, against all odds and at any cost, to emigrate from Europe’s most impoverished nation to Italy for work. In the novel, an Orthodox priest is deserted by his wife for an art-dealing atheist; a mechanic redesigns his tractor for travel by air and sea; thousands of villagers take to the road on a modern-day religious crusade to make it to the promised land of Italy; meanwhile, politicians remain politicians.

Moldovan writer Vladimir Lorchenkov tells the story of a group of villagers and their tragicomic efforts, against all odds and at any cost, to emigrate from Europe’s most impoverished nation to Italy for work. In the novel, an Orthodox priest is deserted by his wife for an art-dealing atheist; a mechanic redesigns his tractor for travel by air and sea; thousands of villagers take to the road on a modern-day religious crusade to make it to the promised land of Italy; meanwhile, politicians remain politicians.

Chapter 8

Not far from the amusement park, a pair of storks rested atop the roof of a house and calmly looked each other over. Nearby sat two men: a stovemaker and the owner of the house.

“Put your hand on the chimney,” said the stovemaker.

“It’s hot! I’ll burn myself,” said the owner reluctantly.

“The smoke …”

“Touch it!!” shouted Eremei.

The owner cautiously brought his hand close to the chimney. Gathering his courage, he made contact. Then, laughing with surprise, he thrust his hand inside the chimney all the way to his elbow.

“It’s cool!” he blurted out in amazement. “The smoke is completely cool!”

“Like ice,” smiled Eremei. “Like real, cold ice. There it is. Put your hands on it, feel it. If you can touch it, it means it’s real.”

For Eremei, the stovemaker from Alexeevca, the world was divided in two halves: the real and the invented. Alexeevca, Eremei himself (whom he could touch with his own hands), his tools, tile stoves, his wife Lida, his daughter Evgenia, the grass in the fields, the land, the well where the sun went down in the evenings and in the morning struggled out of to dry off and spin in the sky – all these belonged to the first category. In the category of invented things, Eremei, who didn’t much go for philosophy, placed what he considered to be paranormal phenomena. Things like ghosts, honest state agronomists, an Olympic victory for the Moldovan team in the upcoming games in China in 2008 and … Italy.

“It doesn’t exist. There’s no such thing as Italy,” he categorically declared as he made his rounds. He’d dramatically smack his trowel against the clay, keeping rhythm with his own argument. “The whole thing was invented by international swindlers!”

“What do you mean?” the educated folks would ask in surprise. “Italy’s right there on the map.”

“Give me a map, I’ll draw anything you want on it,” coughed Eremei. “Of course the country exists. But it’s obvious they don’t need our workers there. It’s all just an elaborate scheme.”

Eremei would explain himself to the gaping public who often gathered in the village to listen to the stovemaker. He was a well-respected man. “They say all sorts of things. They claim two hundred thousand Moldovans have already gone there, but tell me, has anybody here ever seen this place they call Italy?

One of the listeners timidly spoke up. “My neighbor told me that his cousin’s son from Marculesti went to Italy. Every month he sends them two hundred euros!”

But Eremei made a mockery of the bickering villager by suggesting the young man from Marculesti had long ago been sold for his organs. The group gasped and Eremei went about building the stove like an old hand. He loved to chat while he worked, like an ancient Russian storyteller singing a folk song.

“It’s obvious. These swindlers, they make a heap of money selling dead bodies,” he said, lifting his trowel. “And one of the con men’s got half a conscience. So he sends some crumbs back to the boy’s parents.”

“What do you mean, crumbs?” they said. They were trying to trip up Eremei with his own words. “We’re talking about two hundred euros!”

“For us it’s a banquet,” Eremi laughed, “but for them, it’s crumbs.”

The villagers became sadly silent, picturing the kind of wealth that makes two hundred euros seem like crumbs. Eremei put down his trowel and went to eat lunch. He always ate at home, but picked up his conversation when he returned as if there hadn’t been a nearly hour-long interruption.

“Of course, I don’t think they sold two hundred thousand Moldovans’ organs in Italy,” he said, softening up after lunch like any man. “Some must have survived. I bet they’re being held in captivity and forced to work. Their captors are making millions off them … No, billions! And so they send some crumbs to the relatives.”

“But why go that far?” asked the owner of the house where Ermolai was working. “The swindlers can exploit the Moldovans either way.”

“This way, nobody asks too many questions,” answered the stovemaker. He’d already thought about it, and now he took a minute to bask in the effect his words were having on the villagers.

And there really was an effect. Eremei was not only an unpredictable, witty and original orator,—the village teacher on his deathbed had called Eremei the Cicero of Alexeevca—he was also a superb stovemaker. Legends were constructed about his stoves. Everyone knew the smoke that came out of a stove made by Eremei always came out cold. This meant, he diverted all the heat from the fire inside the home. Many times his rivals tried to see exactly how the stovemaker complicatedly arranged the flue; each time they simply became confused, crying bitterly and gnashing their teeth at their own impotence. And why wouldn’t they? One stove cost nearly two hundred leu, or twenty euros. That was reason enough to consider Eremei a man of substance. Such substance, in fact, that thieves broke into his house on more than one occasion. But they never found anything and left empty-handed.

“Where do you hide the money so well that nobody ever finds it?” the stovemaker’s wife asked him after one unsuccessful robbery attempt.

“Look over here.” Eremei mysteriously beckoned to Lida and raised his finger. “Not a word to anybody.”

It turned out Eremei kept all his valuables in the stove, directly underneath the flame. But he’d designed the stove so brilliantly that the place where the flame blazed was always cold. Lida, in awe of her husband’s intelligence, thanked God for sending her such a good man and went to work in the fields. Eremei counted his money one more time and laid it under the flame without burning himself. This was his second secret, which he never even told his wife: fire had no power over him, it only brushed his skin like a cat’s tongue licks the hand of a loving owner. Then the stovemaker righted himself, remembered Italy, which was the only thing people were talking about, and snorted. He heard footsteps.

“Papa,” said his daughter, coming up behind him. “Lend me four thousand euros. I want to go work in Italy.”

Chapter 9

After the stories about planting trees in Balti, the shooting of homeless dogs in Soroca, and the prime minister’s press conference, it was time for a story about Italy on the local news.

“According to information from the Italy-Moldova Institute for Cooperation and Growth, the number of Moldovan citizens working illegally in Italy could reach two hundred thousand. The chairman of the Institute, Doina Babenko, announced on Tuesday that they are undertaking measures to support Moldovans working illegally in Italy, but according to …”

The nasal voice of the newscaster on Moldovan TV blabbed on.

Annoyed, Eremi turned off the set and paced the room, hands stuffed in his pockets. It was a little awkward these days for Eremei to debunk the myth of Italy. His daughter, after all, was working in Bologna. It was surprising, but Zhenya had made it to Italy, called once she got there, and said she’d been set up with a job. She was slowly paying back the debt to her parents. As it turned out, Italy did exist. At least that’s what Eremei wanted to believe. Otherwise, he’d have to admit that the international mafia of human organ traffickers was sending him money after they’d sawed his daughter to pieces. Besides, Zhenya called regularly to report on what she was eating, how she was living, and to assure her parents that she wasn’t smoking and everything was great. Eremei was happy—he loved his daughter—but since her departure he’d withdrawn into himself and become gloomy. It wasn’t the separation from his daughter that was to blame.

“So, Eremei, there’s no such thing as Italy, eh? Isn’t your daughter there now? Maybe she doesn’t exist either, ah?”

The stovemaker was badgered by friendly heckling. In his distress, he not only lost weight, he even stopped sleeping. His work was uneven, nervous. Eremei wasn’t making mistakes, but a lot of people noticed that the smoke from his stoves had started coming out a bit warm. The stoves weren’t retaining all the heat for the houses and the people inside. Some spiteful critics even conducted an experiment. They drove to the regional center and stole a thermometer from the local medical clinic. Then they slipped the device into the chimney of a house where Eremei had built the stove after his daughter’s departure. A day later they fished out the thermometer.

“Thirty five degrees,” announced the village’s other stovemaker, Anatol Tkachuk, grandiosely.

The smoke from Anatol’s stoves still came out seventy degrees Fahrenheit, as hot as a June afternoon. Clients didn’t exactly flock to him. But everybody in town understood that Eremei was getting old. The master was losing his skills.

“Listen, Eremei,” Postolika the farmer said to his friend Eremei sympathetically. “Why not just admit you were a bit off the mark when you said there’s no such thing as Italy. I mean, people aren’t animals. They’ll understand. They’ll forgive you. They might stop teasing you, too.”

“People aren’t the problem,” admitted Eremei. “I’m the problem. You see, it’s as though everything around me is collapsing. It turns out all these years I’ve been telling people tales …”

The townsfolk became more convinced about Eremei when rumors started circulating that Zhenya, his daughter, was coming from Italy to visit her parents. It was a special event. Up until now the most contact there had been between Moldovans in Italy and their relatives back at home were telephone conversations and money transfers. Eremei painstakingly prepared for his daughter’s visit and even built a portable fireplace in her honor. True, the smoke came out—just a little—on the warm side.

Lida, the stovemaker’s wife, exited the house on tiptoes and set off to drown herself. But Eremei knew the nearby river was a half-meter deep at its max and that his wife, a strong swimmer, could never drown in it. Too bad. “I wouldn’t mind drowning, either,” thought the stovemaker, but I haven’t got the strength.” He had reason to despair. Their daughter had arrived at the train station like a princess, all decked out and with loads of cash. But after meeting Zhenya there, her parents couldn’t rejoice over her visit. Not after she told them what she’d been doing. And to all her mother’s howling and the unspoken anger in her father’s glance, she shouted maliciously, “So what? All of our people over there are doing the same thing. At least the younger ones. And even if you don’t sell yourself openly, either way you’re going to sleep with your boss if he says he wants it. What else am I supposed to do? Go home? To where? You call this a home? You’ve never seen a real home. This isn’t a home – this is trash, a hole in the world, eternal humiliation! Moldova! Chisinau’s alright enough, but if you want to live there you’ve got to have money for an apartment, right? And where are you going to find that here?”

She was just like her father: she spoke every harsh word with painstaking precision, the way Eremei would fit a tile onto the stove so that it was solid and plumb. And with each of his daughter’s words, his spine stood straighter and straighter, though he realized there was no escaping the shame.

“What am I supposed to do here?” continued Zhenya. “I hate this trash, I hate everything in this place! It’s all so depressing and nasty!”

Her mother sobbed, the stovemaker stared gloomily at the flame, and the daughter went to bed. Lida went off to drown herself, but an hour later she came back from the river, wet and tearful. Eremei gave his wife some motherwort tea, which put her to sleep like a child, and he sat in Zhenya’s bedroom before dawn. For a long time he feasted his eyes on his daughter’s wretched face. She had wronged them, but they loved her terribly.

And when the sun came up Eremei strangled his daughter and burned her body in his mightiest stove, where he usually forged tools for the machinists. He burned not only her body, but her ashes, too. When Lida woke up around noon, he told her their daughter had left of her own volition. And of course his wife was surprised, but she was so weak and disheartened she couldn’t talk about it. With time, her doubts about Zhenya’s departure faded and her faith in her husband was renewed. Even when he said that Italy didn’t exist. And in the village, too, they believed him. What’s not to believe? After all, Eremei the skeptic’s daughter was supposed to come for a visit, and it seemed like she never had. Even the phone calls from Italy had come to a halt.

By summertime Eremei had build another stove. This one burped out puffs of the coldest, blackest smoke you’v ever seen. And in contrast to Italy, you could touch it with your own hands.

“Fifteen degrees,” they announced grandly at a village

gathering. “Freezing!!!”

____________________________________________________________________

VLADIMIR LORCHENKOV, writer and journalist, was born in Chisinau, Moldova, the son of a Soviet army officer, in 1979. In his childhood he traveled across the Soviet Union and other socialist countries, including Transbaikal, the Arctic, Byelorussia, Ukraine, Hungary, Mongolia. When his family returned to Moldova, he studied journalism and for ten years was in charge of crime coverage at a local newspaper. Lorchenkov is a laureate of the 2003 Debut Prize, one of Russia’s highest honors given to young writers, the Russia Prize in 2008, and was short-listed for the National Bestseller Prize in 2012. Lorchenkov has published a dozen books, and his work has been translated into German, Italian, Norwegian, Finnish, Serbo-Croatian and Finnish. He is married with two children, and still lives in his hometown.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

ROSS UFBERG is a writer and translator. A graduate of Hamilton College, he is a PhD Candidate at Columbia University in the Slavic Department. His fiction, translations and journalism have appeared in The Forward, Heeb, Harlequin Creature, Habitus, GALO and other places. Memoir of A Gulag Actress, a translation from the Russian with Yasha Klots, was published in 2010; Beautiful Twentysomethings, a translation from Polish of the memoir of the writer Marek Hłasko. Ross is a co-founder of New Vessel Press.

____________________________________________________________________