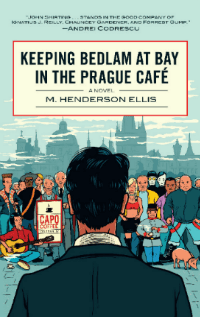

KEEPING BEDLAM AT BAY IN THE PRAGUE CAFÉ

(an excerpt)

Not long ago, John Shirting–quiet young Chicagoan, wizard of self-medication–held down a beloved job as a barista at Capo Coffee Family, a coffee chain and global business powerhouse. When he is deemed “too passionate” about his job, he is let go. Shirting makes it his mission to return to the frothy Capo’s fold by singlehandedly breaking into a new market and making freshly postcommunist Prague safe for free-market capitalism. Unfortunately, his college nemesis, Theodore Mizen, a certified socialist, has also moved there, and is determined to reverse the Velvet Revolution, one folk song at a time. After Shirting experiences the loss of his sole “new-hire” — a sad, arcade game-obsessed prostitute — it is not long before his grasp on his mission and, indeed, his sanity, comes undone, leaving him at the mercy of two-bit Mafiosi, a pair of Golem trackers, and his own disgruntled phantom.

Not long ago, John Shirting–quiet young Chicagoan, wizard of self-medication–held down a beloved job as a barista at Capo Coffee Family, a coffee chain and global business powerhouse. When he is deemed “too passionate” about his job, he is let go. Shirting makes it his mission to return to the frothy Capo’s fold by singlehandedly breaking into a new market and making freshly postcommunist Prague safe for free-market capitalism. Unfortunately, his college nemesis, Theodore Mizen, a certified socialist, has also moved there, and is determined to reverse the Velvet Revolution, one folk song at a time. After Shirting experiences the loss of his sole “new-hire” — a sad, arcade game-obsessed prostitute — it is not long before his grasp on his mission and, indeed, his sanity, comes undone, leaving him at the mercy of two-bit Mafiosi, a pair of Golem trackers, and his own disgruntled phantom.

Pigstroke

Monika ate at al-Jamilli’s every day. For lunch and dinner she would enjoy the same meal: a gyros (stuffed until the pita was bursting at the seams with extra cucumber, onions, and tzatziki sauce) with fries on the side. She constantly smelled of lamb, having found its gamey olfactory qualities the most effective weapon in repelling overanxious clients. As of late, Shirting would join her at mealtime, though he would opt for al-Jamilli’s falafel, the spicy little balls of mashed chick peas rolled and fried in front of his eyes by Jamilli himself. (Shirting thought the presentation good marketing and recommended Jamilli start expanding his business across the city, perhaps even have a falafel delivery service—Jamilli just laughed and sat back down on his upturned milk crate.) The stand was situated in a delightful location—the courtyard of an incorporated building on Na Příkopě that one had to enter through a vaulted corridor. The area was canopied with the branches of ageless oak trees and had the feeling of a small park in the city center. Squirrels hunted around the diners’ legs for fallen scraps of pita and stray, breakaway balls of falafel.

Shirting had made good headway in securing the attentions of his desideratum. Persistence had paid off, not to mention the easy money he represented to the working girl. It can be told that much of Shirting’s savings had gone toward buying time enough to earn her confidence. But that deductible having been paid, on occasions such as these, he was only expected to cover the meal, which he did without complaint. With the aid of the pocket dictionary he had secured at the American Hospitality Center, and a pantomime performance worthy of a kabuki actor, Shirting had made clear his overture of friendship, and perhaps future employment. She wasn’t adverse to the idea, and thus allowed Shirting to tutor her in English over gyros and the apple tea Jamilli served in tulip-shaped glasses.

They sat at a small round plastic table, a pile of napkins at the ready for when Monika inevitably dribbled tzatziki sauce onto her exercise book, which was now opened to her daily homework assignment. Shirting noticed that, though she had written only a few words of the essay he had assigned her, she had gone to great lengths to ornament her unformed scrawl with illustrations of pigs, and had also adhered several panda stickers to the page. Shirting asked her to read her essay aloud: My teacher is some small wildebeest. He is a name John Shirting. My name is Monika. He is the baddest person in this world. I feed him the cats. He is my darling. Dear Monika. The way she pronounced her w’s as v’s, calling him a vildebeest like a tarted-up little vampire—if that wasn’t going to stir his slumbering libido, nothing would. And all things considered, he was pleased with her progress. She had shown a certain talent for memorizing the names of animals, of which it appeared she was quite fond. The result was that she knew the English words for ocelot and condor, but could not give directions to the National Museum. Shirting indulged this interest in hopes of using it as a springboard into more useful vocabulary, not to mention basic grammar, but anytime they strayed from the subject of animals the girl’s interest waned. This had prompted a field trip to the city’s underfunded zoo, where they gazed at grumpy baboons kept in bare cages, drugged-up pachyderms, llamas that spat at anybody who got too close, and harassed, neurotic goats in the petting zoo that shrank from the touch. Monika had worn an ermine stole and ventriloquized sympathetic messages to the caged animals through its tiny preserved head.

“Look,” Shirting had said, “I am walking away from the marmoset. I am walking toward the anteater.”

“Marmoset, anteater,” she repeated, smiling.

“No. Toward. Away,” he said, making a few illustrative steps.

“Marmoset! Anteater!” she insisted, then hid her face behind the cloud of cotton candy he had bought for her.

Things were not going much better at Jamilli’s. Shirting had set up a neat little exercise based on Mad Libs, one of his favorite childhood games. All Monika had to do was provide a verb, noun, or adjective into the blank spaces Shirting had scratched from his Pooh book, and he would later read the hilarious results back to her.

“I need a verb,” Shirting prompted. Monika stared without visible comprehension.

“You remember verbs, the things that do.”

“Superman,” she finally said.

“Superman isn’t a verb, it’s a person. Jeepers, he’s not even a person, he only looks human.”

“Superman does,” Monika countered.

“It’s true, Superman does, in fact he does far more than his fair share, to be sure. But he can do all he wants and he still won’t qualify as a verb. Look how the Mad Lib plays out: ‘If you happen to have read another book about Christopher Robin, you may Superman that he once had a swan.’ It’s a nice idea, but it just doesn’t work.”

Monika pouted and threw one of Shirting’s fries to the squirrels.

“Look Moni,” Shirting pleaded, “I am only trying to help you. How can I listen to you bespeak your great sorrow, which I sense, if you don’t have the words to communicate the experience? If you are like me, then the place you reside in is far more remote than your mere physiognomy would let on. If that place is in the sea, then these words I teach you are the stepping stones between us. If that place is in the forest, then these words are a trail of breadcrumbs. If it is in the sky, they are each a flap of a wing. Each word, I encode with a bit of myself, so when you speak it, you will recreate me in your memory. It is my charm.”

Shirting paused for a breath, then continued: “As for myself, I speak to you from across a great chasm, one that only grows greater every day. But this island of myself is a clean place, I can tell you, free of interlopers and malingerers. I have dusted the cobwebs from the eves and shaken out all the rugs. There are polished surfaces aplenty, here. Are you following? What I’m trying to say is I’ve changed the sheets of myself, made the room of my heart ready for a visitor. But the invitation I issue is written in English.”

He had, of course, lost her completely. She pulled a crayon out from the box he had given her as a present and began filling in the pig doodle with an aquamarine blue.

“Well,” he said, and not without any small amount of determination, “if you won’t learn English, then I will endeavor to learn Czech. Like Orpheus descended to Hades, I will descend into that language’s depths if only to bring you up and out. Now, let’s have a little. Come on, give me a word.”

“Strč prst skrz krk,” she said, smiling malevolently.

“Come again?”

She repeated the sentence.

“She tells you to stick your finger down your throat,” Jamilli said, laughing.

“Str . . . str . . .” he sputtered, but no matter what acrobatics he put his mouth through he couldn’t get past the Falling Wallenda of the tongue required to pronounce the Czech ‘r’.

“As much money as you Americans have, you cannot buy a vowel,” Jamilli cracked wise.

“Jamilli, as much as I respect your entrepreneurial and, no doubt, refugee status, I must request that you limit your interest to the carving up of your adorable lambs. As for money, it does me no shame to inform you that I am down to my last shares of bean stock, which I am loathe to sell as Capo’s is gobbling up the market at such a ravenous rate.”

“Poor and without language—it is how I came to this county, too,” Jamilli said, bringing them fresh tea.

“Jamilli, while I’m sure you have quite a dramatic and heart-rending story to tell—perhaps CNN would take a liking to your narrative—I am now concentrating the entirety of my effort on the young lady, whose tale is equally filled with woe and second-world hardship.”

“But I am her Genie. She says so herself. One day we will disappear and you may look for us in the bottom of a beer bottle. In many bottles you will look.”

“My dear sir, I will ask you to stand off. Besides, beer does not agree with my biochemistry. But I would take another falafel, if you are not too busy.”

“Of course, of course.” Jamilli retired to his shack.

But Shirting had gotten overheated for nothing. When he asked Monika to tell him the story of her childhood, she struggled to get out a few words—pig —being one of the audible ones, and then went mute. “Pig,” she had insisted, then delicately rapped her fist on the table, upsetting her glass of tea.

It is perhaps true that children of deep loneliness find one another in later life, are drawn to each other unconsciously. Is that what drew Shirting to Monika in the first place? Some unspoken recognition, some elemental attraction? A telepathic communication delivered unbidden, received unnoticed? If she did have the gumption, if not the words, to describe her experience to Shirting, she might have lent credence to that theory.

Like Shirting, Monika was also brought up without her parents, who had been deported by the previous regime to a workers’ camp in the Lower Urals. She had been left in the care of a grandmother, who lived in the town of Mikulov, which was separated from Austria by ten miles of yellow mustard fields. The proximity of the “West,” even though Vienna lay soundly to the east, did little to relieve the boredom of small town life, which, even under socialism, resonated with small town life almost anywhere. Monika was barely thirteen years old when she caught the attention of a man the townsfolk commonly referred to as the Devil. The Devil had once been a history teacher, but had been dismissed from his post when he had referred to the occupying Russians as “invaders” rather than “liberators.” The new regime put him to work clearing the town square of snow in the early hours of morning—a position that, in the summer, found him sweeping litter from the streets. His old colleagues had been instructed not to talk to him, a circumstance that turned him into something of an untouchable, a member of a caste of the excommunicated. After that, his bitterness had consumed him, and he spent the better part of his afternoons drunk in a pub beneath the fortress ruin, cursing the Russian assistors under his breath. To simplify his sentiments: he felt corrupted by the world, and resolved to corrupt right back. It was not long before he began to take notice of the girl on her way home from the technical school every day, quiet and, as far as he could tell, friendless.

It took little courting to bring them together. Soon Monika was riding around in the Devil’s Trabant (the fender held on with electrical tape), neglecting the chickens her grandmother had bullied her into caring for. She listened to Radio Free Europe on the Devil’s shortwave radio, taking in her first experience of jazz with the Devil’s hand down her shirt, the Devil’s own wife and child asleep in the next room. In beating her when she refused his advances, the Devil did little to deter her affection for him. Monika retuned to him time after time, wearing her bruises like badges of honor. It took an act of, in her estimation, much greater cruelty to cleave her from him.

The Devil, for her amusement, had stolen a piglet from the farm of a neighboring town and presented it to her with a little pioneer’s kerchief tied around its neck. She accepted the gift out of duty to her man, but in time grew to love the pig, which she led around town on a rope leash. She called him Lexy Fluxum, the name written across a package of candles she had seen in a store. She fed it on milk and cornmeal, adding in chicken carcasses and egg shells as they came.

One day, the Devil decided to take her on a trip to the Zapova Lakes. He escorted her into his car (he had tried to let her drive, but took over when he found she wasn’t strong enough to turn the Trabant’s stiff steering wheel), taking the piglet along. The animal rode between them, taking in the scenery. Halfway there the Devil made the animal move to the back seat. “Jealous of a pig,” she had chided him, secretly believing that his anger confirmed his love for her. At the lakes he rented a row boat, and in between swigs of the local jug wine he had brought along, rowed them out to the lake’s misty center, Monika shivering up against Lexy Fluxum, as the autumn had provided an unseasonable chill, a taste of things to come.

They were the only boat on the water, the Devil kicking back into the serious business of his wine, which Monika allowed Lexy Fluxum to slurp from her cupped palm. The tipsy beast hoisted itself up onto the bow of boat, gazing out at the water beyond, a swinely maidenhead. In its gaze, Monika projected her own: she saw distant lands, new lives, hope. The Devil had promised to take her to Prague when he had the money. She kept a packed cardboard suitcase in her closet, where her grandmother wouldn’t notice.

It took little more than a kick—more a flick of the foot—the way an able player can send a soccer ball arching through the air with the smallest motion, to send Lexy Fluxum tumbling, squealing into the water. Though drunk, the Devil deftly grabbed then restrained Monika, who could do nothing but watch the little pig bob like a cork in the choppy water. In time his squealing stopped, all his labor dedicated to staying afloat. As the pig’s body shivered, so did Monika’s, a mute scream forming on her lips when she saw the water around Lexy Fluxum changing to the color of the wine in the Devil’s jug. If he would have allowed her, and it might have crossed his mind to do so, she would have jumped in right after her pet, into the slick of blood that inked the water around it. The piglet would die not from drowning, but from the cuts along his neck, the result of the paddling of his too-short legs, his sharp hooves cutting his own throat.

The Devil, in time, brought it aboard again with the flat end of the paddle, presenting the mortified, sopping corpse to Monika with a waiter’s flourish. Monika did not cry, but instead held the ball of chilled flesh to her chest. Later that night, the Devil would roast the piglet over an open fire for a group of rowdy friends, melting the fat over slices of brown bread and red onion. Monika too would partake in the feast, the molten fat taste henceforth reminding her of love corrupted.

But none of this was for Shirting to know. For her next homework assignment he encouraged her to make up a story of the blue pig she had so eloquently illustrated. (She would complete the task, wearing her aquamarine crayon down to a gnarled claw by opting to depict the story in graphic form, embellishing it with cameos from an otter, a porpoise, and a tap-dancing coyote.)

____________________________________________________________________

M. HENDERSON ELLIS is the author of the novel Keeping Bedlam at Bay in the Prague Café (New Europe Books, February 2013). He lives in Budapest, where he works as a freelance editor at Wordpill Editing, and is a founding editor at Pilvax magazine.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by M. Henderson Ellis:

“I’m Still Your Fag” a short story on Smashwords (also available as a free e-book)

Bedlam reviewed in the Winnipeg Free Press

Interview with the author at Hungarian Literature Online