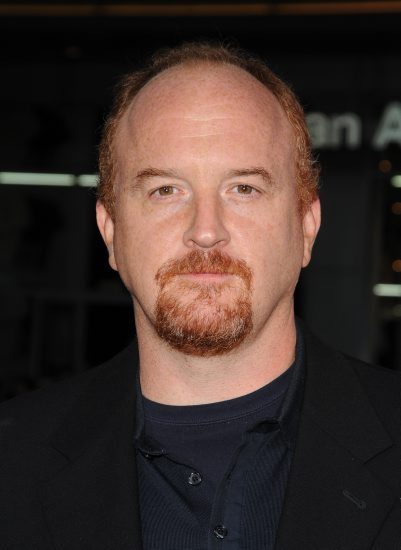

Few viewing this page will be unfamiliar with the recent e-hubbub over Louis C.K.’s comments on the Conan O’Brien show regarding smartphones, only the latest hilarious outcry against the role of technology in humanity’s deteriorating sense of self and compassion that the comedian has delivered with the working-class humanist insight that makes him so palatable to mainstream audiences.

Some have begun to question whether comedians today loom larger than writers as the antennae of the race, providing society with both a banana peel and a mirror of sober self-reflection. What hasn’t been said is that C.K.’s litany against smartphones is essentially Emersonian.

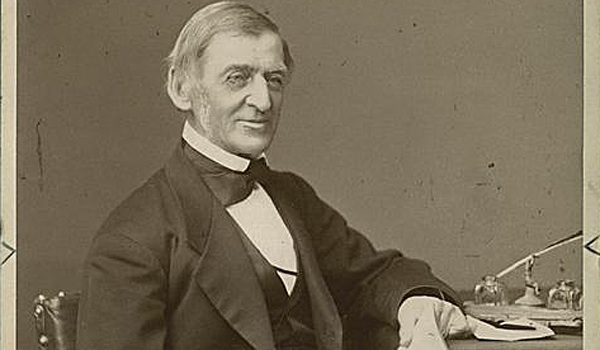

In his essay “Self-Reliance” (1841), the seminal American writer and thinker Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) defined genius thus: “To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart, is true for all men, — that is genius.” C.K.’s bit about smartphones certainly qualifies, as does the work of all the best comedians, who not only believe in their own sense of humor, but also in the verisimilitude and clarity of their particular point of view.

Let’s look more closely at C.K.’s words, which begin as an observation about his own children: “I think [smartphones] are toxic, especially for kids…They don’t look at people when they talk to them. They don’t build the empathy.”

“The empathy” that C.K. thinks such a necessary quality to instill in children is, as he says earlier in the interview, a tool to help them “get through a terrible life.” The deconstruction of empathy is one part of what he objects to about our hyper-mediated society. Another is the willingness of most humans to be swept under the wave of technology of which smartphones are only the most visible example, and which is capitalism masquerading as a tool for equal-opportunity lifestyle enhancement. C.K. has placed himself in opposition to prevailing opinion, and in so doing has tapped the undercurrent of society’s disappointment that all of our gadgets have at best failed to make us more content.

Then again, life doesn’t seem to have been much different in Emerson’s day, though perhaps the connection speed was slower. He writes:

Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members. Society is a joint-stock company in which the members agree for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion. It loves not realities and creators, but names and customs.

C.K.’s complaint is that we’ve been sold junk stocks.

Emerson’s argument depends on a clear division between the individual and society. It is exactly this division that the connectivity of smartphones and social networks corrodes. And that connectivity has significant emotional disadvantages, C.K. suggests, establishing both keyholes and closed doors:

Kids are mean and it’s because they’re trying it out. They look at a kid and they go, you’re fat. Then they see the kid’s face scrunch up and say ooh, that doesn’t feel good. But when they write they’re fat, they go, hmm, that was fun.

The empathy C.K. sees lacking in his children is, according to the comedian, a symptom of their smartphone use, and a symptom of their lack of individuality, or self-reliance, in Emerson’s terms. You have to know what it means to be an individual human being before you can feel empathy for another. But society at large, minus the technology that society has become synonymous with in C.K.’s mind, had already begun to conspire against the individual in the 19th century, according to Emerson.

But now we are a mob. Man does not stand in awe of man, nor is the soul admonished to stay at home, to put itself in communication with the internal ocean, but it goes abroad to beg a cup of water of the urns of men. We must go alone. Isolation must precede true society.

To these head-phoned ears, that sounds much like C.K.’s central point:

You need to build an ability to just be yourself and not be doing something. That’s what the phones are taking away. It’s the ability to just sit there like this. That’s being a person, right? You know, underneath everything in your life there’s that thing, that empty — forever empty, you know what I’m talking about? The knowledge that it’s all for nothing and you’re alone…Sometimes when things clear away, you’re in your car and you go, oh, no, here it comes that I’m alone… That’s why we text and drive…people risk ruining their own and taking a life because they don’t want to be alone for a second.

Perhaps it is fitting that comedians have become our most reliable Jeremiahs. The immediacy of speech as opposed to the written word fits our fast-paced lives. And at least comedians have a sense of humor. That’s more than one can say for Jonathan Franzen’s latest lash against Twitter, brilliant though it is. It is also fitting that C.K.’s attitudes find echoes in Emerson’s writing. In a society that is increasingly inundated with forced and questionably authentic connectivity, whether it is the 19th or the 21st century, it takes a truly self-reliant individual, a man or woman out of time, to tell us who we are, and who we ought to be.

–Stephan Delbos