THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF EVIL

(an excerpt)

Chapter 18

As far as I’m aware, none of the big shots in the Third Reich was a sadist.

All four committed suicide. Hitler and Goebbels did so even before Germany capitulated. Himmler followed when he realized his captors weren’t going to treat him as an important statesman but rather as a criminal, while the hedonist Goering waited until all hope had been extinguished, after the trial was over and the verdict had been passed. They lacked an opportunity, and probably also the will, to tell their story – the losers accounting for their actions?

The sadists were more likely to be found on the lower echelons of power, among concentration camp guards, secret police interrogators, and the like. Their “professional” sadism, however, enjoyed the blessing of society, relieving them of a bad conscience. You can’t send a regime to the gallows or to prison, so in Nuremberg it was its representatives who were in the dock, while in the subsequent trials it was those who implemented it in practice. If they recalled anything at all, all of them – except perhaps for the sometimes defiant Goering – claimed to have been innocent victims who had only followed the orders of their superiors at the time. None of them was able to tell us much about Evil.

Václav Mrázek testified that, whenever a longer period passed without him killing someone, he would get a headache; thus, he committed his murders for health reasons, so to speak. Other serial killers have mentioned an internal pressure or tension that increased between murders, which might be regarded as withdrawal symptoms. This suggests that murder is addictive and that murderers, like drug addicts, need increasingly frequent and more powerful fixes. Nobody went to the trouble of finding out whether as a child Mrázek had abused animals, even though experts regard this kind of behavior as the hallmark of a future serial killer. Other factors include a dysfunctional family background, an absent or ineffectual father figure, physical and sexual abuse in childhood, and the case histories also tend to feature injuries to the head. Often these people are also habitual liars and thieves. The psychological background supposedly includes a sense of injustice, a feeling of having been treated unfairly by society, which prevents them from assuming the position in society they believe they deserve. Most of these murderers nurture unrealistic ideas of grandeur that they’ve failed to put into practice, making them feel unappreciated.

And who wouldn’t? Quite why a sense of embitterment gives rise in some people to the murder of innocent individuals, mostly total strangers, is likely to remain a mystery to all, including the perpetrators themselves. Sure, they seek pleasure just like everyone else; but how come they find it in violence and killing? None of this has the effect of intensifying the actual sensual pleasure in any way – the raped skin doesn’t become any smoother, the dead face any more winsome; the friction of one mucous membrane against another any more intimate. And why should it be them, rather than someone else? They are not the only ones to have grown up in dysfunctional families, been exposed to domestic violence, suffered head injuries, abused animals as children…

When he lived with his aunt in the countryside as a little boy, they would often collect firewood and fir-cones in the forest. Once, finding himself in a clearing, armed with a branch he’d just picked up, he spotted a giant toad sitting on a tree-stump in front of him. It stared him straight in the eye, blowing up its warty skin threateningly. Its repulsive look made him swing his stick at it instinctively, without thinking, killing it with a single stroke. The frog’s soft insides exploded, spraying shreds of skin over the stump and leaving him with a strange feeling of being stifled, almost as if the toad had jumped at his throat. No, he didn’t feel guilty about having killed a living creature; after all, it had been truly disgusting. In later years he was astonished to recall how the intensity of his aesthetic outrage had driven him to kill. He hadn’t felt the slightest doubt – he didn’t like the toad, so: bang! And the subsequent irritation, the physical heaviness, had sprung of the recognition that his intervention hadn’t solved anything: the toad squashed and dead was even more repulsive than it had been alive. These days, I hesitate if I have to kill so much as an irritating mosquito, but that hasn’t made me a vegetarian.

“Forgive me if I’ve disappointed you,” I said to my wife Ivica. What I had in mind was that I hadn’t loved her the way she expected, the way she believed she deserved to be loved. I guess she felt that someone else, Goebblesky for instance, might have loved her better, more. It’s immaterial whether she was right or not; what matters is that she felt that way. She might have been happier with someone else and the idea that I had denied her that chance made me feel guilty. I was sincerely sorry that, through my fault, something inside her may have stayed dormant, something that might have blossomed if awakened. That she hadn’t drained the cup of love to the full. However, she scented irony behind my words.

“What makes you think so? Have I ever said anything of the kind?”

“C’mon, it’s obvious. I’ve even disappointed our dog,” – the trusting creature had expected me to have him healed but I had him put down instead – “so it would be a miracle if I hadn’t disappointed you.”

It wasn’t advisable to start an argument, certainly not with a woman and about love. That is their specialty, whereas I am just an ignoramus. Never, not even in my wildest dreams, had it occurred to me that I deserved to be loved, and whenever there was any indication that this might be the case, it just filled me with a sense of quiet wonderment. One isn’t supposed to look a gift horse in the mouth, and as I’m not a vet it would have been pointless anyway. I remember… yes, I can still recall the longing, the sense that somewhere in our body there is a crack which could seemingly only be filled by that one single unique person, and the fact that the crack remains the same while the unique people vary doesn’t convince us that it might be otherwise. Paralyzed, we stand on the platform as the train departs, until one day it’s departed for good.

The only form of love that lasts is habit. But I didn’t say that to Ivica as I didn’t want us to fight. The difference between us might be in the interpretation – the word love, or whatever it’s called, would never come up in my narrative. Not because I don’t attach any importance to love – I wouldn’t talk of food either even though it’s something I couldn’t survive without. It’s just that I don’t consider love, like sex or regular bowel movements, something I should take credit for, a personal achievement. It’s simply something that happened to me. In Ivica’s narrative love would presumably feature quite prominently. One of the reasons women want to go to heaven is because they hope God might fall in love with them. Of course they’re not sure about that, but you never know.

“What do you have in mind, specifically?” Ivica asked, and went on without waiting for a response. “After all, you’ve never told me you loved me, so I have no reason to be disappointed. Or is this about mistresses? They’ve nothing to be envied for, they can only be pitied. They’ve been tricked, poor things.”

No, this is not the right way to proceed. I’ve never kept a diary and even if I had, this is not the sort of thing I would have recorded. I can’t remember and therefore I cannot provide her with an exact reference to that unique moment, even if by some chance it did occur; but if she says it didn’t… Ivica has a tendency to exaggerate but in matters like this she can be relied upon. If she says I haven’t, even if I had said it to her a hundred times, then it’s never happened. She’s quite right, she’s bound to know better. I’ve never told her I loved her – what does she think the word means anyway? – but in that case, damn it, what about the silent wall of her acceptance that I’ve felt behind my back all my life? This approval of my being the way I am, if need be? How can we tolerate this, damn it; how can we put ourselves at women’s mercy in this way? It’s not them, after all, it’s us who have discovered how the Universe works and who invented the automatic dishwasher. Yes. But they are the ones with milk in their breasts. So what more do they want, what is it about this I-love-you business?

“What I have in mind, for example,” I said, “is that I’ve never got very far in life. Haven’t even made it to principal, as you hoped.”

“What do you mean, ‘as I hoped?’ How do you know that? Have I ever said anything like that?” Attack is the best form of defense, and after a few glasses of wine Ivica charges, like veritable light cavalry. I love her reddened cheeks sounding a clarion call for the attack, her eyes glistening like a drawn sword… I love her when she’s like that. My Ivy-Bivy. She’s up for a good row any time of the day but that can only mean that she thinks I’m still worth it. That she hasn’t written me off yet.

“It was you who didn’t want it. Even though you would’ve been up to it. Except that… You were named Meritorious Teacher of the Year, and that sort of thing doesn’t happen just like that! You were invited to join a textbook writing team and if you’d accepted it would have been you on the ministry’s advisory board instead of Húsková. But that would have required a bit of effort from the Herr Professor, so it was easier to pretend it was infra dig. That’s fine by me, just don’t try to claim now that … I may have had my own opinions about this but I’ve never said a word.”

Let’s face it, Ivica was impressed by that ridiculous title – a scrap of paper; if only the divine authority had added a little extra to help me pay for the obligatory school party! She was happy to bake pagáč scones, to prepare canapés and even to spare me her comments later that night when slightly inebriated female colleagues started clinging to me… Funny how women are attracted by any, even halfway erect, penis of power.

“Oh yes, I should’ve joined the Party and started kissing asses. And not just any old asses! And what for? What pleasure would I have derived from it?”

“Pleasure!” Iva said. “That’s it! If someone’s top priority is pleasure no wonder he prefers to hang around bars with females…” She now used the example she’d prepared in advance and had to scour her memory to find more “…or that he prefers to play cards with his chums every Wednesday and to chase a ball around a gym with slackers like himself on Saturdays… By the way, while we’re at it, would you mind explaining what pleasure you derived from all that sitting around the river Váh even though you’ve never caught anything in your life?“

“But I might have done.” And the expectation… in the silence of the riverbank, my backside sore from the metal edges of the fisherman’s chair, that was the only time I felt – sometimes – that I had a future ahead of me. The potential, though never-caught, fish was the only real hope I’d ever experienced. But that’s impossible to explain, especially since I don’t really understand it myself.

“Let me tell you what would’ve really made me happy, if you really want to know. Bending you over my knee, pulling off your undies and slapping your naked butt until you shrieked and promised to be a good girl.”

She fell silent and very earnest for a moment. “You’ve never told me that.”

“What for? You wouldn’t have shrieked anyway.”

She pondered this for another moment. “How do you know?” she said. “Just to make you happy?”

“That wouldn’t have been right, it would’ve felt fake. And now we’re too old for all that.”

She nodded, still earnest. “But couldn’t you have” – she couldn’t let go – “tried it out on a girlfriend, to see if she liked it? Well? Have you tried it? On someone younger?”

Here we go again, barking up the wrong tree. “To cut a long story short” –

I retreated again – “you couldn’t be proud of me. I never gave you a reason to be. And if I’d become principal, you may not believe me, but you’d have had a further reason not to be.” I leant towards her across the table, covering her hand with my palm. She made as if to snatch her hand away at first, as if wanting to withdraw from my touch to some safe haven, but then she controlled herself. Her fingers were cold.

“Tell me, what’s made you stay with me this long?”

“I wonder about that too sometimes.” She seemed to think this over for a while, to have figured something out, but then she just waved her other, free hand. “You wouldn’t understand anyway.”

Probably not, seeing as I was asking. “You know,” I said, “lately Sheriff and I have been discussing all sorts of things in the evenings and I’ve realized what it is. The thing that’s really hidden inside me, my real talent, is that of a criminal.”

“Nekem mondja,” Ivy-Bivy said in Hungarian and it must have been the first time that evening that she laughed. “You’re telling me.”

____________________________________________________________________

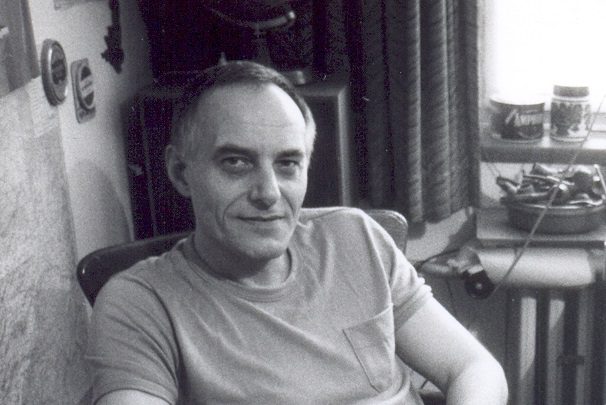

PAVEL VILIKOVSKÝ was born in 1941 in Palúdzka, Slovakia. He has worked as an editor in a publishing house and for a literary monthly magazine as well as having worked as a translator. He debuted with a collection of short stories Citová výchova v marci (Emotional Education in March, 1965) and his other publications include Prvá veta spánku (The First Sentence of Sleep, 1989), Krutý strojvodca (The Cruel Engine Driver, 1996), Posledný kôň Pompejí (The Last Horse of Pompeii, 2001) and Pes na ceste (Dog on the Road, 2010) among many others. He won Slovakia’s Anasoft litera award in 2006 for his collection Čarovný papagáj a iné gýče (The Magical Parrot and Other Kitsches, 2005).

Vilikovský’s collection Ever Green Is… (Večne je zelený…,1989) was published in an English translation by Charles Sabatos in 2002.

____________________________________________________________________

JULIA SHERWOOD (née Kalinová) was born in Bratislava, Slovakia. She has worked as a translator from English, Czech, Slovak, German, Polish and Russian into Slovak and English and is Chair of the NGO Rights in Russia. Her translations include Samko Tále’s Cemetery Book by Daniela Kapitáňová, Freshta by Petra Procházková, and My Life with Hviezdoslav by Jana Juráňová due to be published by Calypso Editions in 2014. She has also translated work by writers such as Uršuľa Kovalyk, Michal Hvorecký and Leopold Lahola among many others. She is Asymptote’s Editor-at-large for Slovakia.

PETER SHERWOOD is the first László Birinyi, Sr., Distinguished Professor of Hungarian Language and Culture in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has translated the novels The Book of Fathers by Miklós Vámos and The Finno-Ugrian Vampire by Noémi Szécsi as well as stories by Dezső Kosztolányi, Zsigmond Móricz and others, along with works of poetry, drama and philosophy.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more about Pavel Vilikovský:

Interview with the author in Literalab