THE GIANT SUITCASE

I couldn’t have even hoped to see my end – one so magnificent, grand and sudden, so maddeningly deceptive and even baring its teeth in a triumphant grin above my petty and thoroughly delusive dream of greatness. And it came upon my dream and devoured me.

Every damn day I despaired, and every night I nursed the thought that one day I would be recognised as a great scholar, a top literary critic in my small country. (Oh, that horrible little word ‘small’ that I despised like a mortal enemy in my private war against pettiness, miserliness and all human meanness!) I lived on that thought, I loved it, I shared it out in vivid vistas drawn from secret depths of my heart: splendid symposiums, brilliant lectures, yes, and standing ovations, rich flattery, adulation, homage and toasts in my name.

But, oh, how I had to go through hell to finally get a professorship at the university. How many leagues through louts and loafers, how much catering to the ‘Central Committee comrades’; I became a virtuoso of that inexplicable yet most profitable art of despising people but serving them submissively, feeling the blood vessels twitch in your face as you draw it into a half-smile and readily put yourself at their disposal. I swallowed this ideology hook, line and sinker, as you will surely suppose, becoming a ‘passionate fighter for the cause’, and of course I triumphantly appropriated all the known rhetoric – indeed, I became a great trap-setter and underminer, with treachery and zest. I even learned to be an undertaker, quietly burying others with intrigues, like a knife in the back, with comradely greetings. Those are just rungs, you poor people, rungs in the pecking order; I scaled them carefully, on my guard, one at a time, onwards towards the top. Push down whoever is beneath you, lick the heels of whoever is above, lick until he stumbles, then see him down, and you can continue one rung further up. Oh, the art of it!

But in vain. My own greatness no longer suited me, it was all too paltry. So what if I was a university professor, a literary critic and ‘godfather in the Central Committee’? So what if I ruled the roost? Though power is certainly sweet – I could take your average literary flake, for instance, and make him a ‘first-class writer’. I could bury others overnight, without a trace, without writing a single word. They fell into anonymity with my tacit blessing. I must admit that I derived pleasure from those little souls who were never again able to emerge from the hole I had forced them into with such subtle bliss. But all that, you poor people, all that greatness and the power itself seemed insignificant to me in my unbridled, unbroken, unbelievable urge for something even greater. How much greater could I imagine myself to be? To tell the truth, an insignificant bit of flattery can get me fantasising about greatness. What’s in a bit of flattery, you ask. But it caresses me so sweetly, so tenderly, warming the cockles of my heart; coogie coo it goes, or blares, or whispers secretly but seductively. Sweet as sugar are its charms, and enchanting its words: You are great, it says.

I was snagged, I resolved, I tossed and turned, but there was no escaping that aching thought, that gnawing in my heart: how would it be, the devil advocated, my dear Boshe Tuppencev, how would it be if you joined the Academy? Huh? And that ‘Member of the Academy’ after your name? And all the privileges, huh? Perhaps you’ll retire one day, and then as an honorary critic and academician you’ll lick your lips, your cheeks will take on a ruddy radiance, you’ll prevail with authority, scorn and generosity – a figure whose brilliance will outshine every petty peril.

I made it, as it turns out, though it took many ruses. But anxiety began to torment me. Every pettiness plagued me. Imagine – I even changed my step and began to walk more slowly, my head tilted back slightly with a gentle, sly smile, as if I didn’t want to meet anyone who thought himself greater than me. I trimmed my hair, already white, to give it a crest that waved impressively like an imposing imperial plume. But that was not all. I worked on my elocution, through effort and exercise I honed my articulation to sound special – splendid, distinguished, aristocratic. I also adopted that short ‘ahem, ahem’, like a slight cough, for those moments when I had something serious or significant to say to my contemptible colleagues.

But please don’t mention them – not them, my colleagues! Even the briefest passing reminder of them shakes my poor heart so terribly. Because, as you will have guessed, I actually hated them, despised them, and didn’t even let myself think that they could ever be better. In fact, they were the most elemental enemies of my dream of greatness, and one would be happy – and even die happy – to know they did not exist. Yet they are necessary. You have to teach them to flatter you and that that is their duty. You need them so they can give you that mother’s milk. Yes, my dear people, and that is why I hate them. Because I couldn’t do without them, without that milk that one drinks with such relish. That’s why.

And it’s them, precisely them, who even now give me no rest. They stay on to scoff at me, pour their hatred on me and recite funerial flattery to the scornful smile on my dead face, only so as to make a mockery of the tragic and already burlesque burial they’ve staged for me – a momentous masquerade, a show of hypocritical pathos. And me – oh, have mercy on me in my darkness and torment as I lie here, the coffin lid about to weigh down on me, and I cannot drum into them that I am great, or at least many times greater than their puny insignificance.

But I must also say something about how it came to this great deathbed scene.

An invitation arrived at the Academy for me to take part in an international symposium of Slavic scholars from all over the world, to be held in Washington. I come to the Academy, the desk clerk hands me the letter, I open it in haste and read. I blushed, I swallowed, blood rushed to my heart or head and I must have blacked out for a moment, I slumped into an armchair there in the lobby. Ups-a-daisy! My dear Boshe Tuppencev, here is your dream!

But let me explain a few important things. I had been to a number of foreign countries, especially in Eastern Europe, and to the Soviet Union, but I had dreamed of America and looked forward to it with a childish joy. Furtively, in secret, as secretly as can be, like a simpleton with his naive hope waiting for something impossible. To be honest, I had long awaited the opportunity to appear before this democracy, to appeal to the Yankees, to lick their heels, to fawn upon them. Everything before this was just a means, just a tactic for reaching this dream. And the dream was Washington, the Library of Congress! So when the changes came in my country I was exceptionally adroit. I didn’t fall like the Central Committee. No no, you poor people, it’s always the same – all you need are ruses, well-dosed fickleness and feigning, slipperiness and shrewdness at the right place and the right time. That sweetest art of mine is older than any system. So just at the right time I became a defender of democracy, a proponent of turning to the West, and in secret I even thought of finding a way of pronouncing myself a former dissident – that would also have been a good grasp for grandeur in the new situation.

Yes, you poor people: Washington, the Library of Congress. How many words I wasted – wary eyes were watching – before I could become an open devotee of that great Western monster! When I collapsed into the armchair in the lobby of the Academy I was overcome by a pleasure savage and sweet. Good God, Boshe, I said to myself, someone must have heard your words, someone definitely heard them, took them to the top and put in a good word for you. This lovely invitation was proof.

I set off for Washington accompanied by a colleague, a university professor who had also been invited to the symposium. But she, in fact, was my greatest torment. Her presence cast a shadow on my concentration on the visit ahead, and in the end I could hardly bear her. It was a hellish ordeal – that’s putting it mildly – to ignore her and push her to the margins of my mind so that this peril would not plague me, because an inner voice whispered to me that she was at least as ‘first-class’ as I was seeing that she had been invited to Washington together with me.

So it was that I crossed the Atlantic in torment, frequently passing water in the plane’s toilet, but also with excitement. When you arrive, Boshe Tuppencev, go straight to the Library of Congress, march in majestically, flaunt your fame and ask them look in the computer for all of your publications. So several hours before landing I dreamed that a long list of my works appeared on the computer screen, and that filled me with sweet self-admiration. Now I can finally admit it: this was the acknowledgement of my grandeur that I had so long yearned for! I listened to sweet flattery from the attendant librarian even before I was able to hear it, listening with secret ears turned inward to my heart, which hopped from the sweet thought that this was now all coming closer, ever nearer, and here it was… That sweet, sweet self-deception would have been paradise had it not been for my colleague, who I now spotted in the corner of my eye and wished she would vanish, disappear from the sweet dream I was dreaming in the seat, leaning back gently with my jaws twisted into a beatific grin.

One heavy, hellish day destroyed me there in Washington. It was high noon when I set foot on the steps of the Library of Congress with my colleague tagging after me, trying to keep up, unable to restrain my elation.

Darkness, my dear people, darkness; I can only remember a heavy darkness that suddenly descended on me without the slightest warning. And when my senses began to clear but my eyes had not yet found the way back to the beloved light, I heard my colleague screaming above me as if from afar: ‘Help, help! Don’t worry, Professor Tuppencev, a doctor’s coming right away. Don’t fret, it’s nothing tragic!’

Then things slowly cleared, I saw her head above me, and I was lying on a bench outside the Library. My shirt was unbuttoned, she was panicking and splashing water on me to cool my chest, where I felt a piercing pain. And when that evil spirit stabbed me I remembered, as if drawing from a deep well, I remembered a sad gleam on the computer screen where my name had been entered – not one title was beneath it!

I had asked them to check whether that was a mistake, and in the end I even tidied up the names of my colleagues, who in my constricted inner darkness were perils plaguing me, claiming to be better than me. And they were there for sure, listed with all their publications and scoffing at me from behind every letter.

‘Don’t worry, Professor Tuppencev. They brought them in suitcases themselves, they are so petty-minded!’

I think I heard those words humming in my ears, or did I perhaps just hope that my hysterical colleague said them? But what does that matter now? I couldn’t raise myself from the bench even an inch, as stiff and faint as I was; and benumbed like this I shot up into a far, empty blue that exploded with infernal sun-bright lucidity. You ought to have brought them yourself, Mr critic Tuppencev of the Academy, you silly sausage Boshe-washy. If you had brought them in a big suitcase you would have been eternalised. But now it’s too late! Too late, the devil whispered. That whisper echoed inside me and I even repeated it myself. Then all at once, lightly as if melting, my eyelids slid down and shut, blotting out all vision, and I kept looking into the darkness, drowning out of time in a void without voices. Then suddenly out of nowhere a giant suitcase appeared and crashed down on my forehead, dismembering me, smashing me to smithereens – insignificant specks of dust – and as if in a dream I was devoured by my end, from which there was no awakening.

____________________________________________________________________

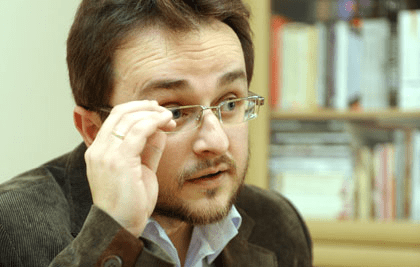

IVAN DODOVSKI was born in 1974 in Bitola, Macedonia. He studied general and comparative literature with American studies and obtained his MA degree from the University Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Skopje. He holds a PhD from the University of Nottingham, UK. He is Assistant Professor at University American College Skopje, where he teaches literary theory, American literature, and Shakespeare. His current research interests include identity politics and contemporary drama. Besides academic papers and literary essays, he has published three books of poetry and a collection of short stories Golemiot kufer (The Giant Suitcase, 2005). The latter was translated into German and published by Erata Literaturverlag in 2007.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

WILL FIRTH was born in 1965 in Newcastle, Australia. He studied German and Slavic languages in Canberra, Zagreb, and Moscow. Since 1991 he has been living in Berlin, Germany, where he works as a freelance translator of literature and the humanities. He translates from Russian, Macedonian, and all variants of Serbo-Croat. His website is www.willfirth.de.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Ivan Dodovski:

“Artist of the Revolution”, a short story in B O D Y