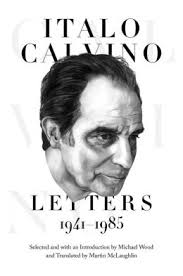

Italo Calvino

Letters, 1941-1985

Selected and with an Introduction by

Michael Wood

Translated by Martin McLaughlin

Princeton University Press, 2013

619 pages

A collection of letters from a writer we admire should offer the double pleasure of insight into his or her life and times, and a view of the work from the inside out.

The success of such collections depends on the verve of the writer, of course. The letters Michael Wood selected for Italo Calvino Letters, 1941-1985 contain plenty of that, as the great Italian writer is irrepressible throughout. But mostly they show a sterner, more business-oriented Calvino than one may expect from his famous, seriously playful short stories and novels, including The Baron in the Trees (1957), and Invisible Cities (1972). With the exception of some of the earliest selections, the focus of these letters isn’t so much the manna of imagination as the work of being a writer. But these are rich pages.

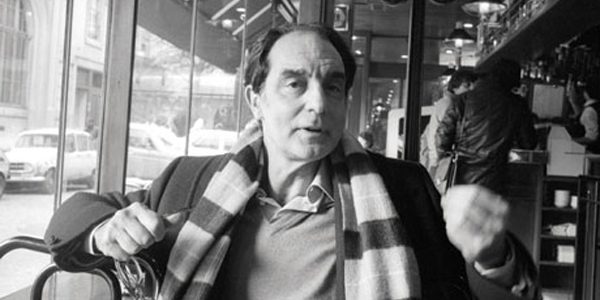

Calvino (1923-1985) led a remarkable life. Born in Cuba to radical intellectual parents, he grew up in rural Italy, where his father was a famous botanist. Initially attending university to study agriculture, Calvino eventually turned to literature against his parents’ wishes. During World War II, his mother encouraged him to join the Italian Resistance Movement. Calvino rode with a Communist group known as the Garibaldi Battalion, fighting in the Maritime Alps for 20 months. During this time, his parents were held hostage by the Nazis. After the War, Calvino threw himself into literature with a completeness that is astounding for a man his age, and is evident in these letters. After a stint as a journalist, he eventually went to work at Einaudi, a leading Italian publishing house, and began his life as a centrepiece of Italian literature and culture, ultimately leaving the Communist Party in 1957, partially in reaction to the invasion of Hungary.

Calvino was a life-long editor, but it is still surprising how many of these letters, translated by Martin McLaughlin, concern matters of business. It seems that, for Calvino, writing was business. And with it came responsibility. Part of that responsibility was to engage in a generous exchange of ideas, about literature, film, philosophy, philology, art, and politics with some of the greatest artists, writers, journalists, and thinkers of his day.

What is most clearly evident in this collection is not the warmth of the individual, but the paper trail of a man who considered writing equal parts craft and intellectual pursuit. That isn’t to say these letters are devoid of intrigue, however. One of the remarkable characteristics of Calvino’s letter-writing is his insistence on polite formality and frankness at once. This emerges most in his bumptious critiques of writing he didn’t approve of, and his ardent praise of writing he did. He writes to the Rome newspaper Il Contemporaneo in 1956:

Your polemical note on Pasolini on the 23rd gives me the opportunity for a critique of the way in which Il Contemporaneo keeps up with contemporary Italian literature.

Some months ago one of the most important events in Italian postwar literature took place, easily the most important event in the area of poetry: the publication… of Pasolini’s poem Le ceneri di Gramsci (The Ashes of Gramsci). This was the first time for who knows how many years that a large-scale poetic work had articulated, with extraordinary success both in content and form, a conflict of ideas, a set of cultural and ethical problems that a socialist view of the world has to face. Il Contemporaneo did not mention it.

As one might expect, critics and critiques are a constant theme in these letters. Calvino moved his family to Paris in 1967, when the fever of Post-Structuralism was peaking, and in several letters he makes clear his opinions on the relation between the author, the work, and the reader. To would-be interviewer Maria Pia Ghiandoni in Nov 1967, he writes:

What use is it to the critic (you in this case) if the author issues judgments or statements regarding his own works? The critic cannot take as reliable anything the author writes; so this new declaration would have to be subjected to criticism. But if the critic is not sure of his critical tools, he will go back again to the author to ask for further clarification; the author will reply, the critic will have to criticize these new replies, and so on ad infinitum.

There is something farcical about this reply, yet it smacks of Calvino’s fiction, as it blends reality and illusion with the atmospheric completeness of a fairytale.

Another intriguing element of Calvino’s letter-writing is his awareness, most likely brought about by his work in publishing, of the book as text, and his insistence that any story, no matter how “realistic,” is an affect. As he writes to Giovanni Falaschi in December 1982:

The function of mediating between author and public which all publishers and newspaper editors ought to carry out exists so that the publication of a text is not an imposition of the single author’s auctoritas but receives the appropriate amount of collective approval and checking to sanction the text’s belonging to a culture and not just to individual whim. But nobody wants to exercise this function any more…

Even with Calvino’s caveats about what he saw as a decline in publishing, the world of literature seems smaller in these letters, more familiar than it is now. That perhaps reflects Calvino’s prominence on the world literary scene. And indeed, Calvino was very much active throughout the world, in translation and in person. In 1959, visiting the US on a grant, he wrote to Giulio and Renata Einaudi, owners of the publishing house where he worked, describing the city in effusive terms:

I wanted to be someone who lives in New York; after a while I noticed that I was not seeing New York at all but only moving through a sequence of business calls (as writer and as “editor”), lunches, cocktail parties, dinners, evening parties… I am gradually exploring the whole of New York, including the museums, night clubs, and colorful areas that are a must for tourists; certainly I do not have much time for sitting at my desk… The best system is always to keep paper in the typewriter and as soon as I get back to the hotel after a publishing visit or any kind of exploration immediately write my notes…

Michael Wood has made a studious selection of Calvino’s letters, and a provides an insightful introduction that frames his selection in the larger tableau of Calvino’s life and work. Ample notes further clarify many of the personal and historical details, as well as the Italian idioms that appear throughout these letters. It is a book worthy of both study and appreciation.

If this collection of letters is business-like, it also depicts Calvino in the most productive years of his life — career would be too weak a word — in writing. This volume shows the germination of Calvino’s best-known works, and provides new texts in English that capture Calvino’s gracious, mischievous spirit, and his passion for the culture of letters.

–Stephan Delbos