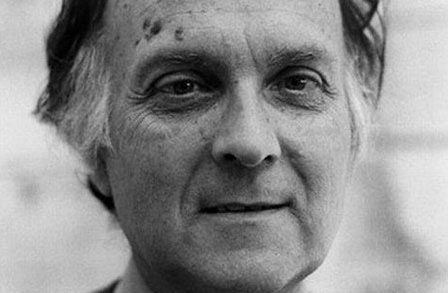

In the world of poetry, which is to say the world, time has the benefit of providing different angles from which to view poets. As collected works, notebooks, and remembrances are published, readers are able to achieve a fuller picture of the poet in question. The San Francisco-based poet Robert Duncan (1919 – 1988) has been one of the most recent cases in point. Herewith, three ways of looking at Duncan: From his archive, from a fellow poet’s memoirs, and from a newly published biography.

Duncan was one of the most vital poets of his generation, someone on the forefront of the New American poetry, pushing borders of form and concept, and establishing new boundaries for what was possible in poetry. There has been a blast of Duncan criticism recently, but there is much in his archive that remains unpublished. The Poetry Collection in Buffalo, New York has one of the country’s largest collections of original manuscripts and poet’s papers. A national treasure for reader-archaeologists.

Here are a few gems from Duncan’s notebooks.

October 11, 1971

We are responsible not just for what we meant to say but for what we say means, in the full responsibility as writers. Why the art of writing is something different from just writing, is this responsiveness to the spectrum of possible readings. Misreadings do not require only corrections of the sights but new calculations that include the misreading in their perspectives and boundaries.

August, 1971

Ideas of what poetry is are, if taken to be simple and definitive, not only various but at odds, giving rise to partisan and even fanatical adherences and oppositions — wars of classics versus moderns, academics versus experimentalists, good versus bad, superior versus inferior.

July, 1954

A poem does not persuade, it entertains our senses.

For an experimental and formally aware poet like Duncan, notebooks are the testing grounds for concepts, ideas, lines, and possibilities. These are the pages that allow the opening of the field, to quote one of Duncan’s best-known books.

But there’s something charming about reading the actual notebooks. An energy is lost when the entries are published between the pages of a book. To hold the yellowing pages, to read the faded ink… an oracle? No, a notebook.

Two recent books have brought Duncan back to the attention of contemporary readers.

Robert Duncan in San Francisco, by Michael Rumaker, is a memoir first published years ago and recently republished in a new edition. The book gives insight into the Berkeley Renaissance, which included Duncan, as well as Robin Blaser and Jack Spicer. As much about the gay scene in San Francisco as about literature, it is a warm remembrance of the poet from one who knew him well. While it does not explicate Duncan’s poetry, it sheds light on the social and political scene that inspired some of his earliest work as a poet.

Robert Duncan in San Francisco, by Michael Rumaker, is a memoir first published years ago and recently republished in a new edition. The book gives insight into the Berkeley Renaissance, which included Duncan, as well as Robin Blaser and Jack Spicer. As much about the gay scene in San Francisco as about literature, it is a warm remembrance of the poet from one who knew him well. While it does not explicate Duncan’s poetry, it sheds light on the social and political scene that inspired some of his earliest work as a poet.

Besides being one of the most important poets of his generation, Duncan was also one of the most important representatives of the pre-Stonewall era of homosexuality in the US. He achieved icon status in 1944, when his landmark essay “The Homosexual in Society” was published in the journal Politics. Not only did the essay cause him to be a representative of gay culture, it caused John Crowe Ransom, then editing the Kenyon Review, to pull one of Duncan’s previously accepted poems. Faced with such rejection, Duncan began to pull away from mainstream publishing, which may have been one of the motivations for establishing a new stream of American poetry. In any case, he was not deterred. In 1951, Duncan began a relationship with the artist Jess Collins, and lived with him for the rest of his life.

Robert Duncan in San Francisco is an important contribution to scholarship on Duncan and this vital era of American poetry, which was a direct precursor to the Beat-inspired San Francisco Renaissance.

The Ambassador from Venus is the fullest biography of Duncan to date, written by the poet and literary scholar Lisa Jarnot. The product of more than a decade of research and writing, this is a vital and informative book that not only fleshes out the events of Duncan’s life from beginning to end, but grapples with his often obscure poetry. The definitive Duncan biography, it stands with Poet Be Like God, the biography of Jack Spicer, as necessary reading for anyone with an interest in this era of American poetry. Perhaps the book’s greatest success is that it balances its portrayal of Duncan as a man with Duncan the larger-than life-poet. The title comes from a remark by Charles Olson, who walked around the block several times before finally ringing Duncan’s doorbell the first time he went to meet him. You would be nervous too, he said, if you were about to meet the Ambassador from Venus.

The Ambassador from Venus is the fullest biography of Duncan to date, written by the poet and literary scholar Lisa Jarnot. The product of more than a decade of research and writing, this is a vital and informative book that not only fleshes out the events of Duncan’s life from beginning to end, but grapples with his often obscure poetry. The definitive Duncan biography, it stands with Poet Be Like God, the biography of Jack Spicer, as necessary reading for anyone with an interest in this era of American poetry. Perhaps the book’s greatest success is that it balances its portrayal of Duncan as a man with Duncan the larger-than life-poet. The title comes from a remark by Charles Olson, who walked around the block several times before finally ringing Duncan’s doorbell the first time he went to meet him. You would be nervous too, he said, if you were about to meet the Ambassador from Venus.

Duncan wasn’t just a leading poet and representative of gay culture, he was also, as Jarnot’s book shows, an extremely intelligent and well-read individual with the ego to match. There are numerous examples of Duncan talking down younger poets and scholars in public forums. His hot-and-cold relationship with poets like Charles Olson and Robert Creeley, who once referred to Duncan as “a lavender,” testify to his difficult personality. Nonetheless, Jarnot’s balanced account leaves the reader with a feeling of admiration, even awe, for this man of letters who broke ground in virtually all aspects of American society.

In time, even the most difficult poetry begins to clarify. In the case of Duncan, one of the central figures of post-war American poetry, these books serve the vital purpose of humanizing the poet while providing keys to his work. But it is difficult to say what Duncan himself would have felt about such publications. As he wrote in his poem “Poetry, A Natural Thing:”

Neither our vices nor our virtues

further the poem.

–Stephan Delbos