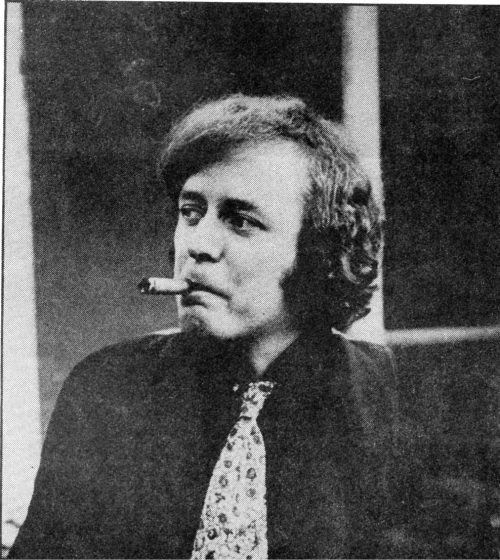

Stewart Parker: A Life

Stewart Parker: A Life

By Marilynn Richtarik

Oxford University Press, 2012

Stewart Parker once jokingly described theatre as “an even chancier business than literature”; plays are like “a box of tricks”—their magic only comes to life in the hands of a skilled performer and in the right context. And indeed the fate of Parker’s work only serves to prove his point.

Though Parker’s plays for stage, radio and television are witty, intelligent and, on the whole, formally innovative, too rarely have they received the limelight they deserve. Marilynn Richtarik’s long-awaited biography of Parker, the product of almost twenty years of work, unpacks the life and work of one of Northern Ireland’s most gifted, inventive, and underrated playwrights.

Back in 1999, a decade after Parker’s death, actor Stephen Rea was to write in his introduction to Methuen’s second volume of Parker plays that his most significant accomplishment was to “imagine the possibility of a future,” to envision “harmonious possibility on the other side of violence” at a time when Northern Ireland was torn apart by the Troubles. For Rea, Parker “restored to theatre a moral as well as a political dimension while adapting to the technical demands of the contemporary stage and media” and for that “he will always be remembered both with affection and admiration”. Grand and heartfelt claims without doubt, yet such admiration for Parker’s work has not translated into substantial critical recognition. His writing, like that metaphorical “box of tricks” has been rediscovered periodically, but on the whole has remained too much on the periphery of what is popularly or academically celebrated as Irish drama. And it is for this reason that Richtarik’s book is so valuable.

The structuring principle of Richtarik’s work is Parker’s relationship with his hometown, Belfast. His story, she suggests, is a “familiar [one] of Irish artistic exile”, a love-hate relationship with the place of his birth and his attempts to respond creatively to the conditions that shaped him. Richtarik, at the outset, surveys the factors that have limited wider appreciation of Parker’s writing. His premature death, the many variables in the production of a play, his diverse output, the difficulties that inhere in Parker’s idiosyncratic dramaturgy and questions of national identity have all conspired against the consolidation of his reputation. Strikingly, she compares his case to that of Brian Friel, doyen of Irish drama; had Friel died at the age of 47 there would have been no Faith Healer, no Translations, no Dancing at Lughnasa. It is a sobering analogy that only adds poignancy to this rich account of Parker’s life and work so brutally cut short by cancer.

Richtarik’s map of that life is detailed and clearly the product of years of careful and reflective research. We begin our journey in Belfast and with a vivid picture of the writer’s working-class Protestant origins. Richtarik charts the stark social geography of Belfast, the habitual cruelty of the school system, the ebbing of his religious belief, the seismic influence of his teacher John Malone, who first introduced him to theatre, and his budding literary aspirations. At university, Parker was to discover a talent for sociability, to make his first forays into print, to get involved in various student publications and with the Drama society. Richtarik illuminates the nuances of student life in 1960s Belfast with a keen eye for detail, picking out the first lines of her portrait of the writer in the making. Then, in a chapter that is one the highlights of this autobiography, she turns to an event that was to radically alter Parker’s world view. In 1961, when in his second year of study at Queen’s University, he was diagnosed with bone cancer and was forced to have his leg amputated. It was a bolt from the blue that would have destroyed many, but seemed to galvanise Parker’s zest for life.

Richtarik’s account weaves family and friends’ memories of this time, with Parker’s channelling of the experience in his unpublished autobiographical novel Hopdance. Hopdance is little known beyond the small world of Parker scholarship, but the extensive quotations from that work here provide a resonant image of Parker’s emotions and reflections after the amputation. What emerges with clarity from this blend of memory and fiction is the extraordinary resilience of Parker’s character, the way he instinctively shielded others from his trauma while coming to terms not only with great physical pain, but with the recognition of his own mortality.

Parker’s path to publication and production is revealed to be a convoluted and stony one, with frequent false starts and disappointments; success was frustratingly slow to arrive, intermittent when it did, and he was frequently rerouted in the 1960s and 70s into teaching, and later, journalism to make ends meet. Between 1964 and 1969, he taught in the USA, an experience that helped him formulate his attitudes to his home place and its history, and also fuelled his enthusiasm for popular music and culture, explored in his lively Irish Times column titled “High Pop.”

When he returned to Belfast in 1969, in order to actively pursue his writing, the conflict euphemistically labelled “The Troubles” was erupting. Along with his own physically traumatic past, this increasingly sectarian and violent situation was to become another major force in shaping his vision as a writer. It was in this inauspicious setting that Parker first seriously directed his attention to dramatic writing and, finally, in 1975 won recognition first with a radio play about the Titanic, The Iceberg, for the BBC, and then with a stage play, Spokesong. Both pieces excavate the terrain of the Northern Irish past with a unique sense of ironic humour. The protagonists of The Iceberg are among the forgotten casualties during the construction of The Titanic, who as ghosts manage to tag along on her doomed maiden voyage. Spokesong, is of course more familiar as one of Parker’s best known stage plays that features an idiosyncratic fusion of history, romance and trick cycling. Both illustrate well the depth of his interest in Belfast stories. If eventually, Parker relinquished Belfast physically, moving first to Edinburgh and then to London in order to pursue projects, its traces are to be found in all his work as Richtarik reveals.

One of the strengths of the book is the way Richtarik mingles accounts of the political and cultural contexts that surrounded Parker with a coherent narrative of the progress of his work. There are rewarding pockets of detail in the first half of the book about the impact of the American Civil Rights movement on Parker’s sense of political justice, about theatre in Belfast and, a cogent survey of the history of Northern Ireland in the 1970s. Following the mid-1970s, Richtarik’s attention turns more to the crises of a more private nature—in particular Parker’s struggles to write and then get his work produced. The often thwarted progress of his many and various projects in theatre, for radio, television and film is thoroughly charted with frequent references to his journal and elaborated with analyses of the play texts, some of which still remain unpublished. The biographical frame, in which Richtarik situates those works, furnishes many insights into the forces that moulded Parker’s dramatic writing. Not least among these is the intense disharmony of Parker’s marriage and its eventual disintegration which is handled with diplomacy by Richtarik, yet emerges as a strong undertow beneath the quirky humour of the work.

Stewart Parker: A Life gives us the first full picture of Parker as a writer, not just within a Northern Irish context, but ultimately in the busy London environment he was to make his home. It is patently a labour of love, intricately detailed and passionately researched. A boon to Parker aficionados and a foundation text for renewed interest in his drama.

—Clare Wallace

____________________________________________________________________

CLARE WALLACE is an associate professor at the Department of Anglophone Literature and Culture at Charles University. She is editor of Stewart Parker Television Plays (2008) and co-editor with Gerald Dawe and Maria Johnston of Stewart Parker Dramatis Personae and Other Writings (2008).