All That Is

All That Is

By James Salter

290 pages

Boldly providing the epigraph for his latest novel, All That Is, James Salter writes: “There comes a time when you realize that everything is a dream, and only those things preserved in writing have any possibility of being real.” The sense suggested by this sentence, that writing is a necessity to life, is evident throughout the novel, which is a departure from Salter’s earlier work and an impressive capstone to an accomplished, if not overwhelmingly laureled, career.

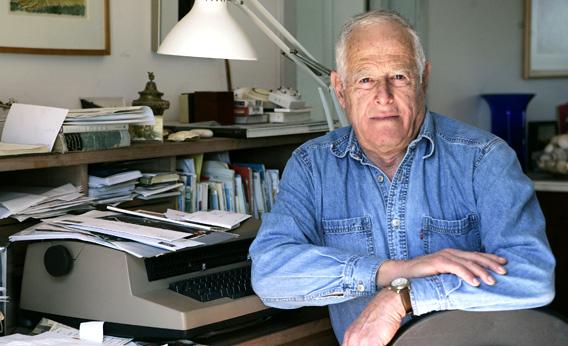

Salter published his first novel in 1957. Since then, he has published only six novels, along with several collections of short stories, memoirs, a book of poems, and a collection of writing on food. Over the years, Salter has been praised for his skill as a novelist by writers including Richard Ford, who wrote “It is an article of faith among readers of fiction that James Salter writes American sentences better than anybody writing today.” (Salter’s sentences have also come in for appreciation on the pages of B O D Y.) But beyond Salter’s skills as a craftsman, what distinguishes him from his contemporaries and makes him a truly powerful writer is his ability to distill longing, that stark, ineffable feeling, into crystalline prose.

Early on, critics drew parallels between Salter and Hemingway, but Salter’s prose is much too lush and luminous to have found favor with Papa. It is a unique combination of cold precision and tender lyricism that Salter will bestow to future generations, along with his vision, which effortlessly reconciles life’s profound and quotidian moments.

Salter is best known for two novels, A Sport and a Pastime (1967), and Light Years (1975), both of which received lackluster and even aggressively negative reviews when they were published. A reviewer for The New York Times Book Review — what was his name again? Oh, yes, who cares — wrote of Light Years, “overwritten, chi-chi, and kind of silly.” Both books have become cult classics. All That Is, Salter’s first novel since 1979, and likely the last that the 87-year-old writer will produce, is almost certain to do the same.

All That Is is a stunning summing up. Firstly of the life of its protagonist, Philip Bowman, beginning with his stint in the Navy in World War II and continuing through his life as an editor for a literary publishing house in New York up to the 1970s. Short chapters brilliantly illustrate the sparkling moments of Bowman’s life, from marriage to divorce, loneliness to love, travels to Europe, betrayal, revenge, and, finally, a kind of peace.

The book is also a summing up of Salter’s life, his writing career, his themes. This is clearly a novel written by a writer who knows it may be his last, and the feeling abides, not least from the novel’s title, that Salter is trying to encompass a life in writing, in writing. It is interesting then, that Salter here abandons two of the most clearly identifiable characteristics of his earlier work: Brevity, and precisely crafted sentences.

Salter’s previous novels have approached his protagonists with a fierce chronological precision. A Sport and a Pastime documents a brief love affair. Light Years depicts the corruption of a marriage over several seasons. Salter’s earliest works, The Hunters (1957), and The Arm of Flesh (1961), drawn from his experiences in the Air Force, show fighter pilots on a single tour of duty. All That Is, however, follows Bowman through the four most significant decades of his life, a scope that is unusual for Salter. That life is punctuated and illuminated by episodic fragments that together present the emotional, professional, sexual, and spiritual lives of his protagonist. The scope of the work is also reflected in the unusual length of Salter’s sentences.

Nick Paumgarten, in his recent profile of Salter in The New Yorker, quotes him as saying that he sought to escape from his reputation as a craftsman of sentences in this novel. That is evident in the long, loose, at times slack sentences that propel it. One might assume that Salter’s desire to cover “all that is” forced him to abandon his painstaking approach to prose. As the title suggests, this novel is no more about New York City publishing than it is about the navy, about love, betrayal, or poetry. It’s about all of these, and more. A lifetime of passions, interests, knowledge, triumphs and follies is packed into these pages.

At times, these threaten to flood the limits of language, resulting in sentences that are unruly, to say the least. This one comes early on:

England had won the war — there was hardly a family, high or low, that had not been part of it — through the early disasters when the country had been unprepared, the far-off sinking of warships that were thought to be indestructible, symbols and pride of a nation, the absolute catastrophe of the army sent to France in 1940 to fight beside the French and then find itself encircled and trapped on the Channel beaches in the hopeless disorder of men without equipment or supplies, everything abandoned in the retreat, and only by last-minute effort and German forbearance be brought home in every boat that could be found, large or small, exhausted, beaten.

It’s the “be brought home” that sticks out like a clunker here, but alackaday, perhaps Salter has rather been a craftsman of paragraphs all along. Here’s one stunner, on the afterlife:

What if there should be no river but only the endless lines of unknown people, people absolutely without hope, as there had been in the war? He would be made to join them, to wait forever. He wondered then, as he often did, how much of life remained for him. He was certain of only one thing, whatever was to come was the same for everyone who had ever lived. He would be going where they all had gone and — it was difficult to believe — all he had known would go with him, the war, Mr. Kindrigen and the butler pouring coffee, London those first days, the lunch with Christine, her gorgeous body like a separate entity, names, houses, the sea, all he had known and things he had never known but were there nevertheless, things of his time, all the years, the great liners with their invincible glamour readying to sail, the band playing as they were backed away, the green water widening, the Matsonia leaving Honolulu, the Bremen departing, the Aquitania, Île de France, and the small boats streaming, following behind. The first voice he ever knew, his mother’s, was beyond memory, but he could recall the bliss of being close to her as a child. He could remember his first schoolmates, the names of everyone, the classrooms, the teachers, the details of his own room at home — the life beyond reckoning, the life that had been opened to him and that he had owned.

This is American prose of the highest order.

All That Is is peopled with a lifetime of affections, both artistic and personal. Poe, Cavafy, Lorca, Elizabeth Bishop, Lolta Soares, Hemingway, Francis Bacon, Auden, Somerset Maugham, Thornton Wilder, Gaugin, Robert Louis Stevenson, Gogol, Shakespeare, Marlowe: All are referenced in these pages, and some at length. These are the writers and artists Salter wishes to point to, making this a novel that is at once absolutely literary and absolutely human. In it, as in all of his best books, Salter depicts a life so full of plenitude, of art, of sex — Salter remains unparalleled in American fiction for his depictions of the carnal act — of fine food and wine, of the world’s great cities, that it is difficult not to be charmed. In short, he depicts life as it should be lived. And yet he doesn’t shy away from sorrow. He doesn’t, it seems, shy away from anything.

Much ink has been spilled in the last weeks about whether All That Is will finally allow Salter to become a “popular” writer rather than a “writer’s” writer. Lovers of his work would wish the best for the man, but finally, that is beside the point. For half a century Salter has been writing some of the finest novels in American fiction. Ultimately his work is all that is. With this, what may be his final book, he has added a crowning achievement: A fine, full novel that passes from literature into life, and back again.

—Stephan Delbos