“Tavern”

By Roque Dalton

Translated by Hardie St. Martin and Jonathan Cohen

There is a particular mixture of awe and disappointment felt upon discovering a poem that has been underserved in publication and criticism. It’s thrilling to find a striking poem from the past, but one also wonders what critical failings have allowed this important text to remain under the radar. This is the case with Roque Dalton (1935—1975) and his long poem from the mid-1960s, “Tavern,” which weaves poetics and politics into a thrilling, multi-faceted narration that sings while it ironizes and comments on Prague, communism, literature, Dalton’s controversial life, and more. It can be found in English translation by Hardie St. Martin and Jonathan Cohen.

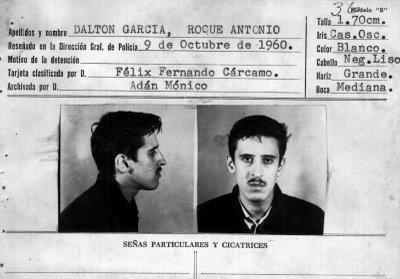

Rogue Dalton’s life story is as strange and exciting as this poem. Born in San Salvador, El Salvador, Dalton turned to poetry and radical politics early on, and was arrested in 1959 and 1960 for inciting revolts against land-owners. He was sentenced to be executed, but the day before his sentence was to be carried out, the dictatorship of Colonel José Maria Lemus was overthrown, and Dalton was exonerated.

In 1965 Dalton was again arrested and sentenced to execution, but an earthquake collapsed his cell, enabling him to dig through the rubble and escape. He fled to Cuba and soon the Communist Party sent him to Prague as a correspondent for the publication Problems of Peace and Socialism. His book Taberna y ostros lugares (Tavern and other Places), which in part reflects Dalton’s two-year stay in Prague, won the Casa de las Americas poetry prize in 1969. Never far from the ire of the government, however, Dalton was executed in 1975 by the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP).

“Tavern” was written between 1966 and 1967 and is set in the Prague pub U Fleků, which remains in its original location today. The poem, which is subtitled “Conversatorio,” is ostensibly a cacophony of overheard conversation minimally mediated by the poet, who offers only the guide of varying typeset to differentiate his narrators. As a communist, Dalton must have felt a certain affinity for the regime in power in Czechoslovakia, yet the poet must have been aware that the situation hadn’t always been as liberal as it was in the 1960s, and that Czech writers, artists, musicians and poets had not always been so free to publish, perform and debate as they were during that decade. This tension is evident in “Tavern,” which probes the topic of communism through the conceit of a barroom conversation, the wide-ranging, open and often political nature of which would only have been possible in the liberal 1960s, an era Russian tanks would soon bring to a close.

Dalton’s poem contains five distinct narrators. The tone and pacing of the poem replicate the meandering, at times impassioned and at times nonsensical nature of barroom talk. The subjects covered over the course of the poem: Politics, poetry, solitude, history, revolution and sexuality, to name only the most apparent, are discussed at length through different narrators, allowing for clashes of opinion and differing conclusions. Dalton’s choice to include competing viewpoints and skewed logic — in effect stretching the limits that would have been imposed by the traditional form of dramatic monologues. Additionally, by setting the poem in a pub, Dalton freed himself from a completely factual telling of the events and allowed for certain nonsensical elements, while providing a natural frame in which the narrative could progress, becoming more emotional as time passes and the narrators become inebriated. As this takes place, the effects of alcohol are not only in the narrators’ admissions, like “I’m already stoned,” but also by the slurring in their speech, such as the expression “mel-low.”

The narrator afforded the greatest number of lines is written in italic font. He seems a bohemian communist, equally aware of literature and politics. A lapsed Catholic, this character professes to have lost his faith in 1959, the same year Dalton was first arrested. The narrator is not from Prague, as he refers to different customs in his “home country,” where “you have to get your supper first” before you can afford to concern yourself with politics and revolution. Solitude — one of two definitions (solitude and art) that come up repeatedly in the poem — for this character is “When the sherry keg is empty,” while art is “what makes us happy.” These definitions confirm the hedonistic nature of this intellectual, who seems to be the youngest narrator in the poem, saying “we the young.” He is certainly the poem’s most zealous narrator, and also its most unforgiving in his assessment of the contemporary world. He disparages the organized Communist party, the Catholic Church and, notably, Allen Ginsberg, whom he reviles for the American poet’s crude behavior and celebrity status. This is also the most idealistic narrator in the poem, calling guerilla revolutionaries the only “pure” movement left.

The NARRATOR featured nearly as often is the capitalized font, the knowledgeable skeptic who says he was “BORN A SOCIALIST,” and categorizes this conversation as one of several “COMFORTING TRIPS WITHIN OURSELVES.” This narrator seems most concerned with literature, both high and low, as he mentions Joyce, Proust, Ginsberg and Penthouse. He is a gossip, declaring “GINSBERG THE POET WENT TO BED WITH FOURTEEN BOYS/ IN PRAGUE ONE NIGHT,” and also makes striking statements about poets, whom he claims are “COWARDS WHEN THEY’RE NOT IDIOTS.”

The narrator of the regular font is the most romantic narrator in the poem and is the only narrator to directly address Lucy the barmaid. He is also the only narrator in the poem to express a predilection for romance. This narrator is sensitive and shy, unable to “get through to Lucy,” and yet over the course of the poem he becomes the coarsest, saying “that sweet ass of yours,” and suggesting “shouldn’t we have another round of beer?” as he steadily becomes more intoxicated. He also refers to his home, Honduras.

The NARRATOR of capitalized italic font is a surrealist babbler, a savant whose wisdom is dispatched in parabolic statements. At the beginning of the poem he predicts “SERIOUS UPROARS OVER AESTHETICS” will take place during the conversation, and proceeds to make those happen nearly single-handedly. Though he makes several striking pronouncements, such as “GENIUS IS A MATTER OF HAVING NOSTRILS FOR SNIFFING/ AT HISTORY’S CROSSROADS,” this narrator is ultimately rather impotent — making remarks that are disconnected from the conversation and all the while calling for calm, to no avail. He seems to live in his own uproarious world where, as he says “THE ONLY FURY IS PEACE.”

The NARRATOR who appears least in the poem is the largest capitalized font, a type which makes him appear to be shouting like a deaf old man. This narrator punctuates the poem with abrupt, often off-topic exclamations, like the passed-out drunk who keeps waking to spout remarks that are as emphatic as they are nonsensical. He addresses everyone and no one at once, saying “GOOD FAMILY MEN OF THE WORLD, UNITE,” and “LOBSTERS ARE IN FROM HAVANA.”

“Tavern” is a significant long poem that captures the tenor of mid-1960s Prague, and all its attendant political, social, and literary uproars. It does so with an inventive and complex structure that puts Dalton on the edge of the mid-century Spanish-language avant-garde. With its conceit of conversation, it is a linguistic and temporary event rather than a strict narrative. Questions are posed and forgotten only to be returned to later in the poem, creating a system of self-reference that replicates the passing of time, though there is no “past” in the poem per se, and its narrators — which are only disembodied voices, after all — have no real past and no history. From its political pronouncements to the allusion to Allen Ginsberg’s 1965 visit to Prague, “Tavern” captures both political and literary history, and shows us the other side of the mirror Ginsberg holds up to reality in his famous poem “Kral Majales.”

—Stephan Delbos