John Quincy Adams by Harlow Giles Unger

Da Capo Press, 2012

Reviewed by Damien Ober

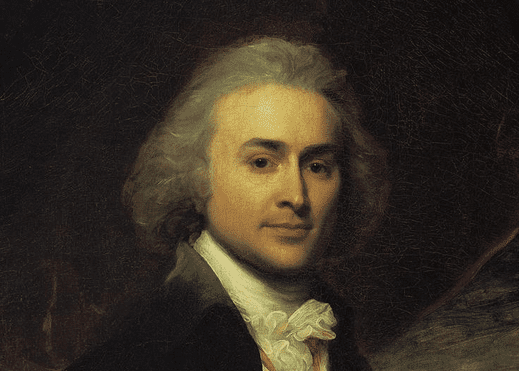

On February 21st, 1848, John Quincy Adams collapsed on the floor of congress. The elderly ex-president, then serving as a representative from Massachusetts, had risen to speak against a resolution honoring the generals responsible for America’s recent conquest of Mexico. JQA had created a late-career renaissance out of opposing the war, but this time he could make no sound against it. Before uttering one word, he suffered a fatal brain hemorrhage. Though he would linger for two days on a sofa in the Speaker’s chambers, this cut-short protest would be JQA’s final act. It was a fitting end for a man who had begun a career of public service at the tender age of 14.

Because of his lackluster presidency, JQA has been largely ignored by popular historians. His early years are over-shadowed by Washington, Jefferson, and Hamilton, his latter by Jackson and Lincoln. But taken from cradle to grave, JQA’s life and perspective outshine all others. It is the perfect framework for a high political epic of the early republic. No figure was so closely involved in as many crucial events throughout America’s birth and establishment. As a boy, he stood on his lawn and watched the battle of Bunker Hill. By ten, JQA was translating for his father as the older Adams negotiated loans to pay for the Revolution. JQA came of age as a diplomat in the courts of Europe, and was there to watch refugees pour into St. Petersburg, Moscow smoldering in the distance. He went on to negotiate the end of the War of 1812, establish himself as America’s greatest secretary of state, acquire the land that would become Florida and Oregon, and lay the intellectual and legal foundation for the Monroe Doctrine. He was elected to the Senate, turned down a seat on the Supreme court, served a term as president and eight consecutive in the House of Representatives. With only a few sporadic breaks, from his early teens to the day of his death, JQA would serve his nation in one official capacity or anther. Because five-volume treatments are reserved for our truly great presidents—of which John Quincy Adams is certainly not one—the challenge of the JQA biography becomes an issue of where to focus.

Harlow Giles Unger, in his new 313 page John Quincy Adams, decides give us all of it. Through the necessary condensing, a tight, rollicking narrative is created, ripe with all the thrilling adventure that the early nineteenth century deserves. The risk of rendering the entirety of such a huge public career is communicating a JQA who is wholly a creature of the political establishment. But Unger is careful to draw attention to JQA’s fondness for the good old belligerent protest. As a student and part-time poet in Haverhill, Massachusetts, JQA took a stand against local Baptists who had outlawed dancing, and years later, refused to abide by Boston’s prohibition on theatre. JQA had seen similar moral domineering in the royal courts of Europe, and he felt it had no place in America. This disgust with “arbitrary power” is a theme that runs throughout Unger’s characterization, helping to deepen and complicate the public JQA and to set the stage for both the life’s and the book’s heroic final act.

But that high point would not be the presidency. Despite the unmatched pedigree and experience he brought to the White House, JQA’s single term is one of the great failures in the history of the office. His vision for the country was a strange synthesis of the pro-business, big government policies of Washington and Hamilton and a dedication to the Enlightenment that was every bit Thomas Jefferson. In his own mind, JQA had combined the best ideas from both sides of America’s first political divide. Through public works and public education, the nation would become a peaceful industrial super-power. Opportunity would be universal and human advancement, not profit, would be the driving engine of a virtuous, scientific capitalism. It sounded good in theory, but “Lighthouses in the Sky” was laughed off the stage. By the end, President Adams was in virtual exile, having accepted his fate with a sad apathy that is equal parts lonely, tragic and pathetic.

Despite a life-long desire for the quite existence of a poet, JQA could not be satisfied as a bystander to the political conflicts of his time. Two years after his presidential defeat, he was back in DC as a member of the House of Representatives. As Unger so brilliantly brings to life, it is in this final movement that JQA shines brightest. It is on the floor of congress that he finds his perfect stage.

The House and its committees allowed JQA an active role in the happenings of the nation, while liberating his ideas and behavior from the judgment of the greater public. Finally he could be the man he really was, a rude, over-educated puritan jackass, at war with his old nemesis, arbitrary power. Now the court fops of Europe and the stuck-up New England bishops were recast as the southern slavocrats who continued to tarnish the ideals of the revolution with their peculiar institution. With an acute mastery of procedural rules and a super-human wit, Representative Adams took a bold stand against southern chivalry, laughing in the face of duelists and pointing the finger of miscegenation at the hypocrites who talked freedom from the mouth and white power from the whip. Left baffled, Southern Democrats were reduced to shouting him down, barking like mad dogs whenever he rose to speak.

It was toward the end of this last crusade that JQA suffered the first in a series of strokes. It was a debilitating episode from which doctors were convinced he would never recover. But like a figure from the great epic poetry he so loved, JQA would rally one more time. Pulling himself from the brink of death, he returned to DC and took his seat in the house. Though he and those close to him knew it would kill him, Old Man Eloquent had come out for one last fight. JQA could see where the acquisition of Mexican territory would lead. At worst, America would become a nation where slavery had cemented itself; at best, a skeletal wasteland torn apart and drenched in the blood of Civil War. JQA fought this future to the end, his great last protest never spoken.

— Damien Ober