THE CAGE DOOR IS ALWAYS OPEN

– by Tom Bass

Editor’s Note: This essay by Tom Bass celebrates and explores the Tangier of Paul Bowles, the city’s American literary godfather. We publish it now in celebration of The Cage Door Is Always Open, a documentary film on Paul Bowles by Daniel Young, which has just been released in Europe. Enjoy!

Tangier occupies a hazy, breezy outcrop of Africa. It smells of drains, salt, smoke. It’s dingy, dusty, a shabby port town like any other along the Southern Straits like Ceuta, Malaga, Melilla, Oran, or Tarifa. It trafficks in measures: drugs, humans, tobacco, tourists, whores. That’s the attraction.

Clinging to the rocks of the harbor are hordes of people who have traveled across Africa from all over the world for a certain dark opportune moment on a certain dark night. They’re waiting to cross. They’re hopping over the wire, trying to avoid the lights erected over the port, and launching across the treacherous waters for Spain.

They were not here before, not so many, never were there so many young men and women ready to cross, to perhaps die in the attempt and wash on the shores of the Costa de Luz.

There’s a man waiting for him just outside the ferry port. Toby’s never seen or met him before but he wants to help. Toby’s been to Tangier and knows where to find his hotel; he’s not going to be threatened by any touts; they’re all equally crooked anyway. The man follows him but Toby’s nonchalant. If not him, then someone else, he reckons.

Toby won’t tell him where he’s from. He doesn’t like that.

Toby won’t talk about business. He doesn’t like that either.

But the tout’s resigned to meeting Toby later after his shower, shave and nap; he’ll have to wait.

Toby ducks into the green and blue themed lobby of Hotel Mamara just down from the Petit Socco. He’s given a spacious and quiet room that looks onto the green tiles of a mosque and he attends to his ablutions, not hurrying, not stalling either. The concierge in the lobby does not remember him at all, though he’s the only guest with late hours.

The man he doesn’t know is squatting on the steps when he leaves. Other men sit in the cafés, smoking their kif, watching football, drinking tea, folded into their crusty burnouses.

From the shadows come hisses: “Hashh, Hashh,” but his man curses back because Toby is his now.

Behind the nougat stand that resembles a police box is a small café that runs long into the night. He’ll come back. Toby continues up the ribbed street. The tout does not relent when Toby tells him, “I’d like to get lost, you can go now.”

He shakes his head and pretends not to comprehend.

Toby flanks the hill of the Neuve Ville, passes a whole series of sweet shops, all that time shadowed by the man, buys something some biscuits with almonds and cloves, finds his way to Café Paris and watches the traffic circle on the sweeping circular veranda, his man interfering with his order for tea and rebuffing the vendors selling one cigarette, one shoe, one glove, one of anything.

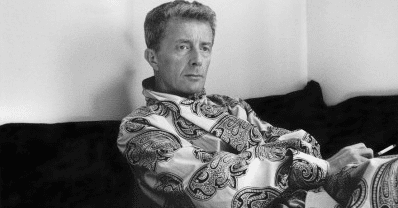

Toby came to look for Paul Bowles in 1998, since he seemed to be about the only reasonable traveling literary man America had produced: moderate, refined, cynical and ruthless. Paul let his characters make their own mistakes in North Africa with a distant cruel eye that rejected anything that Joseph Conrad might have suggested as courage. As far as Paul was concerned, we are all doomed to progress.

Toby didn’t know the old writer was bedridden, blind and deaf, easily agitated by any questions about why he wrote the way he did and what was the “primitive mind.” Toby didn’t know that he was the cold fulcrum to gangs of homosexuals and groupies and that he liked it that way. Toby didn’t know that he lived in a nondescript hovel and his hired man kept jealous watch over any visitors hoping to talk with the barely living legend.

Tangier felt the same to Toby with Paul alive or dead.

Some literary supporters might say otherwise, but the literary vanguard of the Beats and the mystery that made Tangier famous to Americans was over long before Paul died, because America does not care about a man who perpetually misses the literary cocktail party. He left and never went back, except on one sad occasion for a gross tribute. He returned for the strange comforts of being a foreigner in a foreign land.

Independent travelers tend to skip sly Tangier and head straight for the bus station and go on to the imperial cities of Casablanca, Fes, Meknes, Marrakech, or Rabat), but there are reasons to stay a few days before going up to the Rif and joining the drug vortex or into the heartland to collect the perfect souvenir.

Toby ruminates on the path before him, pays mistakenly for his shadow’s tea, drops down the hill to the beach, and trolls the strip next to the sea, the boundary separating Tangier and its customs officers, dealers, guides, hustlers, informers, pimps, porters, purveyors, sailors, smugglers, thieves, touts, and would-be immigrants from Europe, all of them in cahoots with the one another in the hope of canoodling with whoever was unlucky enough to do business with them.

He appears to know where he’s going, so they leave Toby alone for now. On one side street on a corner in the Neuve Ville is a bar that doubles as a bordello. Alcohol and hookers are segregated from tea and drugs in Morocco. Upstairs, girls at vinyl tables and a accompanying drummer and saz player next to the fish tanks and crates of beer. Toby sits down at a whore-free table; two roundies watch him coolly. He scratches a match and lights a cigarette and looks over the place. He drinks Especial — biere de prestige, it says — and a tumbler of Johnny and listens to the music. He’s got one girl’s phone number in minutes.

“Tomorrow,” she says. She’s rotund and jolly but busy tonight.

Toby explains that he’s leaving tomorrow but the more he ignores her the more she’s interested and seems less busy.

Some morose girls are dancing by the time the drummer’s fingers crack and blood splashes through the taped knuckles onto his drum. Another girl in white giggles across the table as her friend starts to shimmer and pulls her white scarf down her hips and pushes the outline of her vulva from the seat of her tight white pants.

When she sits down, Toby asks, “What happens if we meet?”

She just laughs.

The musicians tire and the cassette deck is put into action. Suddenly there’s no more reason to be in the tiled bar surrounded by many rather large, threatening whores.

Some knife-scarred face accosts him along the line of cafés on the boardwalk, but everyone quickly comes to his rescue, pulling the face back into the cafés. Toby continues his trajectory, heading for the medina. Stepping through the keyhole is like inhaling one long breath of corridors and turns interspersed with clusters of men talking in the shadows.

Toby walks past Hotel Mamara, the man from the port still tagging behind.

He’s startled that his target knows the way so well and warns Toby, “You’ve passed your hotel.”

“It’s not time to sleep,” he says.

The tout’s old and wants to go home but he’s going to have to wait some more if he’s going to do business.

The café behind the nougat stand is muted yet busy: men watching football coming from Spain, smoking kif or opium from pipes, rolling hashish joints and drinking teas – getting completely intoxicated in what might be a garage. Toby acknowledges them with salaam aleikum, sits, orders a tea from a gentle grizzly of man in his stained berry blazer as some of the night’s smoke comes to his lips. He rests his back against a gnarled door smothered in vines in the little corner of medina so quiet in the cool night. The dealer wants to do business at the café and disappears to retrieve his gear.

“Too expensive,” Toby says.

The tout’s upset but you know the real price. The man tries to intimidate Toby because he’s now very stoned. But he’s savoring the cloying sweetness of the tea and not paying attention to the offer as he juggles with some pieces of what the tout says is pollen but could be anything.

Toby’s adamant and wins: nice and blonde just as the first call to prayer rings through the streets of the medina and he realizes he must go. He extracts himself from his chair, scrapes himself from the tiny, emptying tranquil café and turns downhill. Swarms of vapor-sniffing kids waver through the streets to the mosque where they will crash after some facsimile of worship.

The concierge is praying in the lobby of Hotel Mamara, praying at the two bubbling fish tanks that light the dark interior. At an appropriate intermezzo, he opens the glass door. Toby thanks him and shuttles upstairs. He listens to the entire sermon naked in bed. The mosque is right outside his room. People cough, expectorate, and kneel as if they’re in his room as they recite the holy verses, the actual words of God, and it’s only when everyone has stepped back into their slippers at the great green gate that he falls asleep in the forthcoming day’s breezy waves of heat and beautiful Moghrebi noise.

A ship toots out in the harbor. Toby opens the shutters and his eyes dilate in the bright hot blast of light. He rests for a moment, stumbles over to the sink, urinates in it. On the bedside table are a notebook and some papers and the chunks he bought from the man in the café in the very last moments of the night.

He’s gone now. Or is he waiting downstairs? No, he must be waiting for someone else. The night of Ahmed (Toby remembers he was called Ahmed) is over and the day of no one is starting, even if he knows he will not be so lucky as to be unaccompanied for more than a few moments.

He pulls on his linen trousers, closes the shutters, burns off a sample from a chunk, and skins it up. It tastes like dung flowers but it hits him immediately and he feels the deep feminine exhilaration of the pollen as it expands in his lungs and mind like a hot bath. He cannot hide behind the slats of sunlight for too long. He wants coffee and some breakfast. He pulls on his sunglasses and puts just as much money in his pocket as he’s willing to part with and slips his notebook into his hand in case he has any thoughts or ideas about the edge of Africa.

Four men tail him from Hotel Mamara and offer to guide him to Barbara Hutton’s house or Jean Genet’s grave (he paid his respects once before at the plain white grave of the old lying man of French letters) or some such legendary Tangier corner, but he stubbornly walks out of the medina and hails a taxi to take him to Café Hafa. He weaves up the hills of Tangier and is dumped between some houses. It’s windy and the sea’s a churning blue below. The light has a brilliant quality. He kicks some stones down the dusty road and tucks through a gate into a house. It has three or four rooms. One is clearly reserved for praying. The other two are for tea, backgammon, and hashish. A samovar gurgles with activity. Boys and men sit around each of the tables. Happily, blankly, they stare out at the sea and the wind bats against the loose panes of what is supposed to be windows. A sequence of dramatic terraces is set with tables and chairs. Each terrace is buttressed with a strip of garden, of cacti and other succulent plants. Some kids are drumming and playing guitar. Everyone’s high and he intends to join them. He’s sits out there but the wind bothers him and he moves inside with the adults.

No one accosts you. No one even bothers to tell you that Mick Jagger was there in 1984 and he’s happy not to know.

Down below the cliffs, children fish from an island and dive into the murky water. On the same rough beach a man puts a camera into a clean nylon bag. He places a snorkel in his mouth, a mask over his large nose, slaps on some fins, and wades out into the sea with the waterproofed camera. Close to where he enters the water is the mouth of a vile black stream, but he doesn’t notice. Not yet. He sinks into the sea and seems to be almost drowning and certainly suffering in the murky but blue water, judging from the spout of dirty water coming from the snorkel. The camera records his breathing, the struggle to not breath in the sewage in the water, his realization that all the things he films in the water are nothing more than bits of turds.

Toby’s laughing, completely blasted on his own gear as well as whatever people are handing him to sample, as he too realizes that this can only be a foreigner, who for some reason (maybe he needs the footage and his ferry back to Spain is about to leave) has chosen this spot under Café Hafa to film underwater when there are thousands of kilometers of Moroccan coast to choose from. It seems so strange that he cannot decide if the man is from the past or the present, if he has not seen the whole episode long ago.

***

Toby leaves his room at the Hotel de Jardin Publique, just outside the Bab Boublouk of the old city of Fes. It’s the hotel with beds like boats stranded on a hot African coast. A group of people squat outside the hotel door talking and smoking. He catches a cab around the old city’s daub-colored walls as the light begins to fade from the sky. He can’t remember exactly where the bar was in Fes’s Neuve Ville, but he finds a coffee-colored young man with a fine, thin mustache and a white dog who thinks he might know what Toby is talking about in poor French.

He says, “I’m Cookie.”

Toby follows Cookie and he takes him to a fancy restaurant. It isn’t what he’s looking for. No, the bar is in what looks like an old Kino behind a padded door that seals in the air conditioning. It has two rooms, tables, a high bar and two kinds of beer, Stork and Especial, that are served from a wooden icebox by a pair of waiters.

Cookie talks with the patrons, men in their tailored shirts and slacks, who are hiding out from the heat and dust of Fes. On a night here several years ago Toby added the alcohol to his delusive high. He does it again, quickly drinking the slugs of beer, until a leering man in spectacles and with puffy lips and shorn hair invites him to his place.

“For conversation,” he says.

“For sniff,” he says.

But not before stopping at the building where he has a hair salon and where he rouses the porter for a toke from the kif pipe.

Sniff is cheap in Morocco, riding on the same networks that transport hashish into Spain.

The hairdresser warns Toby about Cookie and says all he wants is some communication, but Toby understands that a binge of cocaine isn’t what he wants. He climbs into a taxi and says good-bye as the man starts to shout about “wet hookers” and that he isn’t going to have anything to do with those wet ones. a tirade of spittle issuing from his large mouth.

Toby feels something alkaline leak from his nose into his throat that night on the lifeboat of his bed. He squats for the next five days in the baking top floor of the Hotel de Jardin Publique. He eats nothing, then eventually some yogurt and rice. He has a few terrible moments when he cries, pisses, shits, sneezes, and vomits at once. A few times he is stable enough to go to the hammam and smear on the traditional soap made of pressed olive paste, sweat on the hot stones, pour water over himself as the masseuse harasses him and he agrees to let the old blind man stretch out his guts and rub off his skin.

Sons and brothers and fathers and friends are shaving their bodies, trimming their hairs, rubbing and cleaning and washing away the sun. The men and boys move like they have been there centuries, sweating under the mildewed canopy of the hammam. The air is hot and sultry and Toby fills his black plastic bucket and does the same, recovering from the trance of pleasure and pain inflicted by the blind masseuse who has already started haggling with someone else who looks vulnerable.

Toby climbs ever so slowly back into his not so clean clothes. He even feels cold in the foyer, changing at the wooden lockers that have swastikas cut into their ancient grenadine-stained doors. When he walks out into the night, it’s cool and wonderful. The swallows are tilting and singing over the city and he’s once more alive. He drinks a mint tea outside the hammam and talks to a soft-spoken young man in Spanish about whatever.

The boy says, “Las mujeres espanolas muy caliente, dentro. Las mujeras espanoles muy bonita.”

Toby isn’t an espanola but it seems harmless when the boy invites him the next afternoon to his veranda in the slums outside the walls of old Fes.

Toby doubles right after the lane of fish and meat and veg that ends in a woman making fantastic coriander pancakes; he enters the spice merchants who specialize in magic and medicinal goods. He peruses the buckets, cages, and jars filled with Africa. He buys a brace of stuffed chameleons. They’re incense and apparently will make him sleep. He purchases 35-spice in all its raw components, a puzzle of nutmeg, rose, saffron, and all things pungent. On the cluttered shelves rest charms, minerals, seeds, pods and every manner of things that are the gatherings of an unknown continent’s dried plants and animals that all will do something to him if he ingests them.

He can buy poison. He can make someone his slave. He can make someone fall in love with him. He can make himself pregnant. He can induce a miscarriage. He can cork or uncork his bowels.

Red dust appears to stain the entire shop and he meets the eyes of a wonderful girl as he bids adieu,. This is the instant of all his desires and wishes that cannot be.

In the bottom of the medina he recovers in a tea house, found up a stairway must be seven centuries old. Toby sits with the men on the reed mats on the floor against the yellow wall, listens to the radio, watches them play cards, roll joints or fill pipes, suck Marquis or Marlboro, and order teas from the complex copper samovar managed by two thin men with extremely puffy eye sockets holding hard, cold rocks of light. Toby stares at the arabesque tiles and woodwork and loses himself in the sultry hot afternoon, but he has his appointment with Mohammed and he must walk forever up through the medina which, despite the hot hour, is busy with the traffic of donkeys and droves of boys working for the smiths and tanneries. Two almost frozen orange juices restore him. He can’t resist pausing to order with his miserable French three cotton shirts (green, white and a surprise) from an affable tailor before going to the café where Mohammed works.

Together, they walk through the aperture of the Bab Boublouk as they exchange pleasantries, looking at the busy parking lot and the asphalt baking under their feet. Toby is at the gateway. He would feel the same anywhere. Even as he moves and changes environments, in the end he’s responsible if and when things go grossly awry. His ignorance as the stranger is no excuse, although surely Paul would say otherwise. He might even like them to, for his motivationless is a cover for his motives and he will not disclose them, even to himself, nor what he knows, since it is irrelevant to any order since he doesn’t have to live here and face the consequences of daily life in Morocco. He’s ready to forget any responsibilities to the people he loves or the jobs he promised to do on his return as he looks at Mohammed.

Toby pays for a taxi and the car navigates around the city’s rim. The dead are buried outside the walls and the perimeter is filled with dull white graves. Strangely, beyond is more of the ivory city.

He walks in a dry mud street. The taxi turns in the yellow dust. Kids play football, jump rope, fix a moped, or sit in the shade. Mohammed takes Toby into his house, which is a solid, rugged structure of concrete and whitewash. Behind a curtain where the small black and white television plays, his crippled father sits. They all exchange formalities, and the old man nods at the barrier of language between everyone. He’s crumpled into a long daybed and vanished into the aqua room.

Mohammed leads him up the narrow stairs to the rooftop veranda, where some iron bars are still sticking through the concrete. There is a chicken chortling somewhere and a grungy foam mattresses. Mohammed explains about the pobres, the poor, what it is like in his house. His voice lilts with his own naïve youth about the future of Fes and the chances for a boy with some education and smarts. His mother brings tea.

He goes to his room and brings a bag; he unfolds its contents, pictures and letters and a snap of the caliente espanola and correspondence from another woman in Rome and visa applications that did not happen. He could be any other young man in Africa, maybe with a degree, maybe not, with his plastic bag of hope, wishing for some opportunity to do something better than waiting in a shop or a hotel or café for customers. Toby’s a bit ashamed but he asks Mohammed to find some hashish; he also wants a smoke, so he obliges and quickly returns with some cubes of soft pollen for the fifty dirham he gives him. Toby tugs on the dry joints and dozes under the grape vine for a moment. Mohammed is mumbling harmonically in Spanish. There’s a moment when Toby wants to leave but he knows it will take much longer that simply leaving. It cannot be so simple. But somehow it is when he uncoils and taps Mohammed and motions that he’s leaving.

His cinnabar skins smells like wool. If Toby were Paul, he might find that exciting, but somehow he wants to get away from Mohammed’s naivete to somewhere that smells like bread and sounds like jazz as the heat and hashish and companionship wash over him slumped under the grapes.

With some difficulty Toby’s outside again. What was mud is now dirt. The sun’s beating down. He walks among the graves outside the walls of Fes. They’re undecorated, just white stele of stone. Among them are several ceramic kilns. Very young children are loading kilns with cups, plates, and vases, stacking more wood around the strange, alien-like pods that are the kilns. Mohammed takes him to a shack where two older boys are silently glazing pots. Toby looks into their eyes, as if their corneas had melted from exhaustion.

Toby can see into the bowl of Fes and he looks across at the hunchbacked mountains through the blistering heat. He’s amazed by the sooty boys carrying their loads, for which they get a wage of seven dirham a day. They get even less in a more remote places.

Too uncomfortable near the kilns tended by the tiny, wiry children, Toby moves on, sliding down the dry gravel hill through the white graves. There are plastic tarps staked out among the graveyard or tied to a few trees that have not been eaten by goats. He can get a shave or a trim or a massage from the barbers eyeing anyone who looks a little rough around the edges. Some men are being soaped up, but Toby avoids the temptation and would rather shave with his own gunky razor.

The cymbal-like snipping of scissors merges into honking and braking at the main road. He touches his heart when he says good-bye to Mohammed.

“Do you want anything?”

“A few dirham,” he says, “For a film.”

Toby’s noncommittally about meeting Mohammed later. He stoops into a taxi and swing into the Neuve Ville, thirsty for Especial. He finds Cookie with his white dog in the Kino, enjoying the air conditioning and smiling, like Toby is who he is going to do today. The waiter cracks open a beer and Toby uncomfortably knocks back the expensive liquid and orders another as some fries and olives mysteriously appear on his table (the barman already recognizes him) and he can thank himself he earns more than ten dirham a day, more than even Cookie for all his sticky and breathless charms.

***

The train rocks down the track between two mountain ranges. For a while the surrounding hills are like dragons, spiky and serpentine. They’re golden with wheat and it’s only June, shorn like tightly napped fabric. The stalks blow in the air and dash against the windows. The Rif mountains are covered in a film of moisture. That moisture is evaporation from the Mediterranean Sea over the spiny range. It seems to refract the light in an especially opaque, foreboding way. The Middle Atlas to the south are clear and fierce and almost as transparent as slices of almond. People and animals are in harsh and unexpected places. A boy sleeps on a donkey next to a fence of prickly pear. The smell of sand and dust filters through the efficient, refreshing air-conditioning.

A man in some sporty clothes joins you in your compartment. From Toby’s notebook and paper spread out on the orange vinyl seat he notices that Toby speaks English, so he starts to talk in French. After a while, he finally understands Toby don’t speak French or Arabic well enough, so he gets on to talking in English as he adjusts the cords in his nylon jacket, loosens his trekking boots, and rasps assorted Velcro tabs. He launches into some story that he was mugged when he crossed into Morocco from the Spanish enclave of Melilla, that all his things were stolen as if he was a foreigner.

Sure, Toby believes him in his high-tech ghetto gear.

The man congratulates and loves the French state and its entitlements for all its citizens. He pays for no train tickets (one cannot be thrown off the train in France, even without a ticket). He pays no tax. He pays no insurance. He pays no rent. He pays nothing for his children’s education or upkeep. He’s a challenge to anyone as a Moroccan born in Lyon who does some exchanging minidisks and assorted digital whatnot for whatever contraband he’s willing to mule back. He tells Toby about all the islands he has been to, from the Pacific to the Indian to the Atlantic when he is not living off the dole or smuggling.

When Toby builds a joint, carefully mixing the tobacco and pollen in the palm of his hand, the traveler brags how many times he has been to Chechaouen, high in the Rif. Toby’s been there and is afraid to ever return to the isolated, secretive growers’ town where they do not take no for an answer.

Toby’s first contact is reading Marx. He’s representative of the other economy of pollen, hashish, and oil, harvested from his family’s terraces at prices so low that it is difficult to not be greedy and imagine building an entire house of hashish. Naturally, he doesn’t believe Toby wanted to look at the valley of cannabis, and he suggests Toby return with a Jeep to trade.

“I’ll handle delivery,” he says, but Toby knows it would never be that easy.

All the while he’s pushing 100-gram bars of chocolate into Toby’s hand. If Toby accepts, he’ll be given double his order, for him to pay for at his courtesy, such is the hospitality of the growers.

When Toby refuses the deal, despite the ominous twilight and the hungry look of the dealer’s family members, he finds himself pushed away in disgust.

Toby returns to Chechaouen in an old van creaking like an old woman along the rocky hills, high winds buffeting its doors. More dealers are waiting for him in Hotel Ketama, rolling joints and wanting him to buy in bulk from them, too.

But Toby is way too stoned to reply even if they insist he come to a café balcony where he can order harira from across the square, drink orange juice, and chew on a baguette filled with jam and butter, all the while talking some garbled language of Arabic, English, French, and Spanish about drugs (exquisite hash jam and mahjoun in ‘Chaouen) and music (very good wedding bands in ‘Chaouen) and politics (damn good revolutionaries in ‘Chaouen).

The valley and mountains smell like marijuana for all those days and nights, as the plants ripen on the hills, and as Toby settles into the vortex, into the chunks, stretching out on the roof of Hotel Ketama, doing a mix of yoga and tai chi that he’s done forever.

He can almost see Chechaouen out the window, the village nestled against two horns of rock from which it gets its name, but it’s only in his memory.

The compartment reels with the tart smoke of hashish de pobres secured by Mohammed.

Toby has enough time to feel a little dizzy and focus on some transparent blue dots when the train stops and a woman joins the compartment, inquiring in French about a free seat. She turns in her floral suit and sits, her legs dangling above the floor. She slips her gloves from her pink fingers and smiles blandly, gradually turning her head his way. He observes a heavy coat of makeup, a brow growing together, too much hairspray, and some urge on her part to talk.

The smuggler is sneering and snorting at the air. His eyes are as hostile as the sun. His nylon cargo pants rustle malignantly. Outside are succulent bushes that can grow on a single tear. The man’s glaring at her, put in his place by the presence of a well-educated woman. She asks where Toby’s from. She speaks correctly but slowly in answering Toby’s questions of the same formal nature about being a doctor to the irritation of the man in the nylon sports gear.

The man curses her in French and asks her, Why doesn’t you speak Maghrebi?”

He shouts, too. “Morocco needs development more than a king. Until Morocco has infrastructure it will be not even be the gateway to Africa!”

She looks askance at him and stares out the window. Her eyelids are too big for her eyes.

There are few fields where men can work. There’s just a hard, rocky erg, even if it does not always appear to be so. The secular dynasty of the aristocracy (Hassan II replaced by Mohammed V) is corrupt. The king has not had to fight for his right to represent the people because he does not represent them. He’s rumored to be homosexual. His subjects move ahead with tribute. It helps if they’re handsome or if they own half of their administrative district. They can conceivably work between the lines like the French-Moroccan in the compartment, but it is a very tricky, difficult procedure.

The smuggler reaches for the stub of joint and lights it.

“Prostitution, drugs and alcohol are all legal in Morocco,” he says.

“It’s the food of the poor,” he adds, looking like he would not hesitate to beat the doctor if she were his wife, though he claims to be a modern man for progress, perhaps the kind who would publicly beat his wife in the medina as she laughs at first. He beckons and she comes, hyperventilating before he showers her with blows from a benevolent open hand.

***

Toby pays the tariff for six people. He’s grown impatient waiting next to the grand taxi stand in a café smelling of diesel while hoping for more passengers who do not want to go the sea. The grand taxi is his alone.

The man behind the wheel of the Mercedes is satisfied with the transaction and slips in some fuzzy Berber music (communist protest songs) as the car leaves the desert town of Oujda. Toby’s pleased with himself as the sun sets over a field of oil pumps nodding their hammer-like heads, the contested border with Algeria to his right darker than the night wrapping itself over Morocco. He’s pleased that he’s made it this far to where the name of God, people from his past, his relay of minor victories and defeats, all that he has said and done, have been confused with the present. He stretches out on the supple upholstery of black velvet leopard spots.

The taxi halts next to a clump of reeds by the side of the road. A specter parts the canes and tanks up the taxi with plastic jugs of petrol. Although he’s hungry and there are brochette and tajin vendors waiting for customers at intervals along the road, he does not ask to stop. The Mercedes rumbles along and eventually snakes through a gorge as the stars loom in the maroon sky. Across the stream running in its bottom is Algeria. This is as close as he will get to the war-ravaged country. Of course, Moroccans take any opportunity to lambaste Algerians as dirty, lying dogs; there is no love lost along the border that diffuses deep into the Sahara where it becomes the territory of the Tauregs and Berbers rather than any state.

Toby catches the smell of the briny sea and knows he’s close to his destination. The taxi slows once within the grid of the beach town; the driver halts outside a few hotels that he thinks suit a foreigner but the prices are too high. But Hotel Nomades is small, comfortable, and cheap and has a balcony overlooking a grove of fragrant eucalyptus. A spool of wire ends in a light bulb that Toby turns off as he turns the key in the miserable lock; he’s anxious to resolve his hunger.

The sand slips into his sandals as he strolls along the broad boardwalk. He can hear the aerating waves a few blocks away. Outside Hotel Paco he finds brochettes burning on the grill, an appeal for him to step inside. There’s a bar banded in black and white stripes. Berber music clangs on the sound system. He can choose between the red booths separated by screens or the tarped-in patio. A blue portrait of the king on his new throne rests above the bar. A dozen waiters, each featuring a black mustache and paunch, are waiting for his order.

He settles for an Especial and waits for the chicken and lamb kebabs. But from the door designated toilette there emerges an increasing stream of prostitutes. He’s not sure if this is for his sake. The floor manager, in a pastel floral tie swinging over a checked blazer that swamps his torso, escorts the prostitutes to the tables. They ask the waiters to dole out an allotted cigarette or Fanta. Toby stares at the blue gingham tablecloth and peeps from the corners of his eyes. The women come out in pairs. They range from sixteen to forty, all of them buxom and smeared with rouge. The floor manager’s black tasseled loafers tap between the toilette and tables.

As the women appear, so do the men. They invite them to their tables, sit with them, greet them, kiss their cheeks four times, disperse beer and cigarettes, or make some small talk. One short man with a wedding band, navy shirt and blazer orders three beers at once, then agitatedly gathers his nerves, stalking to the toilette, leering at the whores but inviting none. A monster lurks in a corner, alone yet acknowledging regulars, jangling her two gold bracelets, touching her layered curls. The johns scrutinize, suggest, dismiss, touch, recommend, bargain, or compliment as Toby morosely sits and trys to dislodge any ideas of considering the action. The barges of flesh are dressed in some reprehensible style; however, their hair and bodies appear to be washed, at least they are when they materialize at nine o’clock. A girl on crutches with a polio-like walk, atrophied waist, massive breasts and a kind face seems to be the overall favorite. Men lavishly smile at her and she enjoys the attention. An even more voluptuous creature with a bulging brown belly serves beer in the red back room that opens after after 11 when the beer is suddenly double the price. She, too, is eventually put on offer among the men soured on drink, tottering and rocking, seemingly unable to handle what they accept as a fundamental truth staring into her fierce, fleshy cleavage: every woman out of the home is a whore. Every woman unaccompanied by a male relative is a whore. If she is independent (and perhaps not a virgin), she is a whore. She can be nothing else. She is wife or whore, daughter or whore, sister or whore. A new wife is a servant of her new family, whether traditional and poor or progressive and rich. She might have an education but certainly no experience. She has no money. She cannot leave the house. So it is her duty to clean or live in the street, a whore. There is nowhere for her to go but inside unless she chooses Saidia or Agadir.

Toby is in Saidia, a breath away from Algeria, in a bordello trying not to look at the journey written in the whores’ kohl-painted eyes as they wait for the next customer. He remorselessly eats his brochettes; they’re outstanding and you smile knowing that a bordello must follow the golden rule of providing for a man’s stomach as well as his penis as the operation goes on, there behind the toilette at Hotel Paco and the other numerous bars scattered around Saidia. Boys and men are panting over their strange segregation of women but they’re afraid or jealous, wanting to be women themselves. Toby imagines that there can almost not be love, only an oblique lust fueled by hatred. No matter where he tries to not pay attention, he catches the eyes of the whores, and no matter how distasteful, he’s excited by fornicating thoughts of puta, concha, and pussy.

It sustains itself for hours, even after he has gulped down one more Especial, paid and fled to the long red and white dashed curb of the road. A few cars are cruising the drag. He walks out onto the beach and into the darkness.

There are more whores on the beach.

Toby cannot go anywhere in Saidia that night without there being whores and the men who court them. He goes back to his room and agitatedly waits in bed for the morning, his mind alive with hashish, yet another whore.

At dawn he walks to the beach. A mass of blue mountains huddle against the coast. The mountains are Algeria. The sandy beach curves down the Moroccan edge of the continent. Sandbars glitter under the water, cool and refreshing after so many days in the interior. Parasols are already for hire. The sun’s intense and scorching. He enters the clear, blue water, strokes out the heat and anxiousness, soaks in the cooler, deeper water, shivers half submerged out on a sandbar. He trolls the coast as long as his lungs can stand it while keeping an eye on his clothes piled in a little mound on the beach as he slides through the water, the salt stinging and sharp in his eyes and nose.

Men appear from the town studded with cypress and palm, a mix of barracks, bungalows, campgrounds, hotels, and retreats. They’re a mix of conscripts, entrepreneurs, farmers, growers, peasants, pimps, smugglers, students, and workers, all drawn to the shimmering, cool sea. Boys sell nuts, sweets, tea. People unload balls, mats, and towels and get down business: acrobatics, calisthenics, football, running, sleeping, tag, or volleyball. But the Moroccans are avoiding the water.

During another ineffable swim Toby wonders why they refuse to go in any further than their waists. They must not know how to swim or they fear a nonexistent undertow or riptide or sharks or just the deep blue-green water itself; Toby enjoys this private moment drifting in the calm, glassy sea absorbing the long beach of people, everyone vying for a patch of sand.

He quickly dries in the sun and stares for days at the sea of Alboran, hiding under his cotton shirt to keep the powerful beams at bay, the hazy air beginning to inundate the land with liquid heat. Later, he trundles back to his room and dumps the sand out of his sandals and enjoy the tackiness of his salty skin. The afternoon is aimless and airless, without any goal or breeze whatsoever. It resembles a larger part of his life, dreaming about possibilities, as the heat bounces off the asphalt and into the balmy Hotel Nomades. But reality penetrates his mind with opportunities to deny anything he has ever done or accomplished, a potential philosopher king unconcerned with the trappings of power. Since he has no material world to speak of (a notebook, a bag), and except for a few minimal conveniences (Western passport, credit card), his history (identity) ceases (or begins) here in the strange dead ends of his movements; they conglomerate in his mental pouch of experience, an odd commodity these days, bleached by your contact with forbidding, forgotten places. If someone like Paul suggested that it is not characters that act in the world but rather that world acts on characters, it would follow that perhaps the characters have won for now. Paul’s irredentist views on progress have lost to a belief that the world cannot happen. And the world is no longer empty as Paul would have one think. It’s full. Everywhere.

Toby’s ready to turn into the darkness when he dives down into the depths, his ears popping as he stares into the blend of light, sand, and under the mirror-like surface of the sea. He is not flitting from one coup d’etat to another like Ryszard Kapucsinki, he is not Arthur Rimbaud abandoning his verse, he is not finding the source of the Blue Nile like Alan Moorehead, he is not receiving a spear through his cheek like Richard Burton, he is not chronicling genocide like Sven Lindquist, he is not assigned an outpost of progress like Joseph Conrad, he is not backed by the Royal or the National Geographic Society. Nor is he Stephen Biko, Marcus Garvey, Nelson Mandela, or Wole Soyinka. No, he is sitting on the edge of Africa in the square white room that seems to be waiting for an explanation.

He can see that the sun has receded to some degree and that the beach beckons with a more comfortable and pleasing answer than any about desperate Saidia. He scuffs down the road, waiting to fall into the clear, cool water. The sand is churned and pitted from the thriving crowd but he finds a handkerchief of area for his things not far from nine women of all ages who, accompanied by a single male relative, dispatch themselves around a red post in the sand. The women form a circle and allow one another to undress and they adjust to whatever criteria is deemed appropriate by the tankish matriarch overseeing the production, swabbed in a thick white muslin scarf, a deep green jasmine gown with several layers of white bloomers and petticoats underneath. On her thick wrist is a white ivory bracelet. The red post grows higher with garments. Three of the young women have henna hands and feet for luck in marriage and children. The family disperses into the shallows and the male relative talks with the matriarch as Toby observes two sisters with ponytails who emerge from two pale green djelleba and who are remarkably beautiful in their swimming dresses and tights. They intensely look into his eyes and he looks back with relief that they’re not prostitutes but just two lovely girls for an uninterrupted moment under the hot Moroccan sun.

Dr Amos Anyimadu Africatalk re: Ghana sponsorship…

All the bars and bordellos of Saidia are closed on what turns out to be the birthday of the prophet Muhammad. That quiet morning, Toby has a last swim, then returns to gather his kit. He still has his documents and money despite his hair being bleached blonder by each day in the sun and people watching his comings and goings from Hotel Nomades and its excuse for locks. From the shady sidewalk he climbs into a grand taxi. The taxi follows the coast, jolting through Berkane and Nador, and tips him out at the border with Spanish Morocco. He eats a fried fish with his last dirham.

Bedraggled people circle around the tongue of street lined with cafés, everyone observing who gets through, noticing what guards work what shifts, figuring how to pass. Toby scans his pockets and dumps out the crumbs of hash, sand, and tobacco that might be there. Whatever contraband anyone has in the queue is incognito and everyone’s nearly incontinent with fear. Pedestrians have their own separate booth and concrete corridor over the no man’s land separating Nador from Melilla. The Moroccan official is baffled, then suspicious when he reads that Toby has filled in writer for his occupation.

He asks, “What agency he works for, if you are a journalist?”

Toby smiles and wonders what he should report on: oil on the contested border with Algeria… sex slaves in Saidia… growers in the Rif… Berber rights in the desert… corruption in the customs office?

The man can tell what he’s thinking and walks off with your passport while the guards struggle to keep all the fakers from bursting through, for there are times when the frustration boils over into a riot and the authorities’ batons must come out to quell the people. But this is a lackadaisical day when everyone’s too hot or too tired to do anything about this strange land border between Europe and Africa. By all measures, a ferry ride is supposed to separate Spain from Morocco, but from here it takes about three minutes to enter the country of the sun.

The beggars ask Toby for his remaining pewter coins and he hands them over as he waits in front of the glass booth, his sunglasses sliding down his nose and sun trickling down his back and the official nowhere with his passport. The dirham fall into malnourished, cracked hands and disappear into folds of cloth.

The official reappears and scowls a bit and stamps the blue thing since there’s nothing he can do to impede your journey. You’re clean. He sends Toby across the dilapidated walkway. A dry trench of trash is the actual border. A wrecked, bulldozed, burned shantytown is along the Spanish edge and people are hunched under what they can salvage. Some are already selling garros and lemonade among the cardboard and pallets. It could be Gaza or Durban but it’s muggy Melissa. With a glance the Spaniards accept his sunny, salty face. The usual scavengers wait beyond the gate. He ducks into another taxi and goes directly to the port surrounded with more limpet-like touts.

He’s had enough of an aggressive toothless man and he starts swearing in a mix of Hungarian, Spanish, Serbian, and Welsh and they soon leave him alone. He consigns his bags, takes his ticket, and strides into town for some proper drinks in what is totally bamboozling mix, where he can drink on the street and bathe topless on the beach and look a man in the eye and not face any of the taboos of the Islamic world though he is very much so in it, even as he looks at the duty-free everything and orders one San Miguel after another as he tries one bar after another, just killing time, waiting for his boat, savoring cheap, plentiful booze. Placards around town declare what EU money is being spent to renovate 40 square kilometers of European town, the very development money needed in Morocco. The Melilla-ns are confined within this tiny space, connected by ferry service to the mother country, yet are obliged to possess the idea of Spain’s very vastness. But this little speck of Melilla is obviously significant for Spain.

“Todo por la patria,” says the old Fascist slogan on some administrative building. Every plaza has some memorial to some defense of the city. Churches are given prominent position among the radiating boulevards. Behind the high fortification is the old garrison and a stubby lighthouse that still shines on the Southern Straits. Toby drinks himself blind on Beefeater as night approaches in the claustrophobic enclave of old Spanish nationalism.

The same toothless fellow is waiting for him at the port, but Toby won’t talk with him; he looks angry enough that he wouldn’t mind giving Toby a punch or ten as he circulates in the waiting zone.

____________________________________________________________________

TOM BASS is a writer, editor, and translator who has lived on and off in Budapest since the 1990s, where he is involved with Pilvax Magazine He is widely published as a short story writer and essayist.