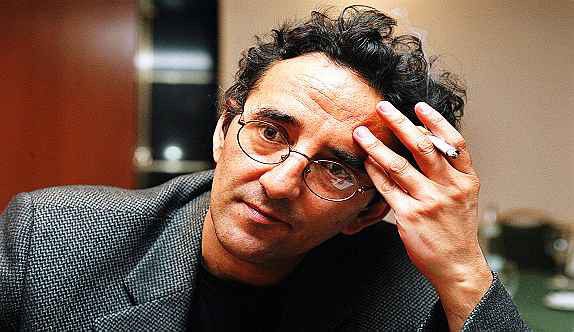

“I wrote this book for myself,” Roberto Bolaño writes in his brief introduction to Antwerp, a novel he wrote when he was just 27 years old but withheld from publication until shortly before his death two decades later, “and even that I can’t be sure of.” The uncertainty with which the maestro of Latin American letters attributes his youthful impulse to create a novel of such disturbed, unsettled genius is certainly in keeping with the uncertainty of the novel itself, which very much reflects the working of an active, unfiltered mind that stubbornly refuses to process its ideas into a neat, conventional package.

“I wrote this book for myself,” Roberto Bolaño writes in his brief introduction to Antwerp, a novel he wrote when he was just 27 years old but withheld from publication until shortly before his death two decades later, “and even that I can’t be sure of.” The uncertainty with which the maestro of Latin American letters attributes his youthful impulse to create a novel of such disturbed, unsettled genius is certainly in keeping with the uncertainty of the novel itself, which very much reflects the working of an active, unfiltered mind that stubbornly refuses to process its ideas into a neat, conventional package.

Written in 1980 during Bolaño’s last year in Barcelona – a time when the author, a native of Chile, “lived exposed to the elements, without my papers, the way other people live in castles” – Antwerp shows the creativity of a writer very much on the verge of something. That we know what that something is – the impressive, prodigious last decade of Bolaño’s life, in which he published 10 novels and three short story collections – is only the benefit of our hindsight. As Bolaño himself acknowledges, “I never brought this novel to any publishing house, of course. They would have slammed the door in my face.”

That alone makes this book worth recommending (and giving, for anyone still on the hunt for literary gifts this holiday season) to writers both at the beginnings and at the zeniths of their careers. Wild, erratic, yet resolutely in control of its many subjects, Antwerp is very much the product of a precious literary mind well aware of the so-called “rules” but simply unwilling to oblige them. To call this work a “novel” in many ways cheapens (by way of burnishing) its endeavour. The young writer at the beginning of his or her career may well appreciate Bolaño’s “scorn” for “so-called official literature,” which was only “a little greater” than his “scorn for marginal literature.”

Bolaño suffered, in other words, from the paradox plaguing many a young writer: the desire to be free from the requirements of fame and yet still be famous. That Bolaño eventually achieved this fame, and did so on his own, incredible terms, makes Antwerp an even more powerful (if more dangerous) model for a young writer. For the mature writer, this early work serves as a refresher – or perhaps as a warning. As one of Bolaño’s narrators, aptly named Roberto Bolaño, points out towards the end of the book: “There are no rules. (‘Tell that stupid Arnold Bennet that all his rules about plot only apply to novels that are copies of other novels.’).”

.

Narratively, Antwerp exists in a dream state, acutely conscious of the horror and appeal of waking life through its magnification and dissolution. Caught somewhere between poetry and prose, the book’s 56 titled sections (one hesitates to call them chapters; perhaps the word episode is more appropriate, though even that descriptor still implies too much linearity) weave a fragmented tapestry in which one voice gives way to another, shifting tenses, perspectives, and even genders, often within the span of a single sentence. Characters appear, appear to be murdered, then suddenly reappear in different forms through the book. Despite the associative logic one might normally associate with poetry, what firmly places Antwerp in the realm of prose seems to be Bolańo’s own distinction between the two: “What poems lack is characters who lie in wait for the reader.” It’s difficult at times to tell whether what’s being described is real or invented, dreamed or seen (the book’s cinematic quality is not unintentional: numerous cinema references abound).

What does become clear, despite the author’s resistance to concrete delineation and plot, is that a girl was murdered, a body was found, and somebody saw it. Those simple facts, for Bolaño, are enough evidence to confound and disturb the essential tenets of so-called reality; they are enough to call everything, from the colour of the ground to the existence of the narrator himself, into question. Once you’ve seen horror, or become aware of horror, Bolaño seems to be telling us, “You can’t go back.” Or perhaps it’s the other way around: once you’ve found a way to hide from the horror, you can’t go back:

You can’t go back. This world of cops and robbers and foreigners without papers is too powerful for you. Powerful means it’s comfortable, a featherweight world, without entropy, a world you know and from which you’re unable to remove yourself. Like a tattoo. In exchange, however, you’d get back to your native land, and the laws that protect you, and the right to meet a very beautiful girl with a dumb voice. A girl standing in the door to your room, a maid who’s come to make your bed. I stopped at the word “bed” and closed the notebook. All I had the strength to do was turn out the light and fall into “bed.” Immediately I began to dream about a window with a heavy wooden frame, carved the like the ones in children’s book illustrations. I shoved the window with my shoulder and it opened. Outside there was no one. A silent night in the blocks of bungalows. The policeman showed his badge, trying not to stutter. Car with a Madrid license plate. The man on the passenger side was wearing a t-shirt with the Barcelona colors, the stripes horizontal instead of vertical. An indelible tattoo on his left arm. Behind them gleamed a mass of fog and sleep. But the cop stuttered and I smiled. You c-c-can’t g-g-go b-b-back. Go back.

Antwerp was first published in 2002 in Spanish (as Amberes), the year before the first of Bolaño’s works appeared in English translation and the year before Bolaño died of liver failure while waiting for a liver transplant at the age of 50. As other critics have noted, Bolaño is a writer whose work appears to have neither a beginning nor an end; whose work appears to be unconstrained by the linearity of time. It makes sense, then, that the first novel Bolaño wrote ended up being the last novel he published, and the most recent of his works to appear in English translation (Picador published the first English-language paperback in 2012).

Bolaño apparently considered Antwerp the one novel he wrote that didn’t embarrass him. Though not a masterwork of fiction along the lines of his later novels, one can see why. Antwerp has a purity of expression and ambition that perhaps only an “unpublishable” novel can maintain. As one of Antwerp’s narrators says, “All writing on the edge hides a white mask. That’s all. There’s always a fucking mask. The rest: poor Bolaño writing at a pit stop.”

— Joshua Mensch

Antwerp, by Roberto Bolaño, is available in paperback from Picador (2012) and in hardcover from New Directions (2010). Click here to buy it on Amazon.com