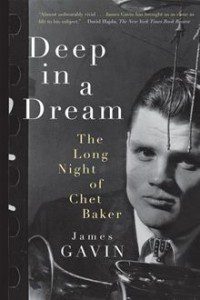

Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker

Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker

By James Gavin

Chicago Review Press, 2011

Last year, Chicago Review Press republished James Gavin’s searing biography of trumpeter Chet Baker, Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker. For jazz fans, Chet Baker lovers, or devotees to the myth of the self-destructive artist, there are few music biographies that so artfully capture the hip era of glamourous decline of 1950s American jazz, an era that for Baker lasted until his death under mysterious circumstances in Amsterdam in 1988.

Baker was famously portrayed in his late style in the film Let’s Get Lost by photographer and filmmaker Bruce Weber, best known for the soft-core-pornographic-chic of his Calvin Klein ads from the 1990s. The film is haunting and beautiful, juxtaposing portraits of the angelic heartthrob Baker in the 1950s with the ravaged visage he had become by the late ’80s, after years of heroin abuse and a general lack of stability. The film is also quite strange, with shots of Flea of Red Hot Chili Peppers fame (who is also an accomplished trumpet player) jumping around on the beach like a gorilla on dexadrine.

Gavin’s biography is a much less sensationalised, and better researched affair. Where Weber is concerned primarily with images, Gavin is concerned with facts, but above all with words. This is an artfully crafted, felt biography that labors successfully to provide a portrait of Baker that is complete, and as well-rounded as his peripatetic, bridge-burning life would allow. The book opens with a stark description of Baker’s funeral in Inglewood, California, Saturday, May 21, 1988.

…It was just like Baker to keep everybody guessing, even in death. He was a man of so few words, and notes, that each one seemed mysterious and profound.

…Everyone at the funeral had his own fascination with Baker. At around 2 a.m., mourners started drifting into the cemetery. They passed the coffin, which was placed on a gurney beside the grave, and sat in a cluster of folding chairs. Everything had been planned by Emie Amemiya, the young woman who had coordinated the shooting of Let’s Get Lost. There in the cemetery, Amemiya saw, for the first and only time, the trumpeter’s second wife, Halema Alli, who had refused to participate in the film. In 1956, Alli had posed shyly with her bare-chested husband for a coolly erotic portrait by photographer William Claxton. Four years later, she wound up in an Italian jail, howling in anguish while awaiting trial as an accomplice in her husband’s biggest drug bust.

Throughout the book, Gavin describes both Baker’s charming side, and how he used his looks and personality to influence people, often to less than honorable ends, such as drug use, theft, disposing of bodies, breaking and entering…the usual. Baker was an unlikely sex symbol when he appeared on the West Coast, playing with saxophonist Gerry Mulligan in the 1950s. The face of an angel and the heart of a demon, as he would later be described. Sure, he was a gorgeous, androgenous jazz prodigy, but he was also troubled, having dropped out of high school, and been kicked out of the Army in part for marijuana use. When he picked up heroin with Mulligan, it was the beginning of the long night of Gavin’s title. He and Mulligan would promptly be busted, and, though Mulligan took the rap, it was the first of many run-ins with the law for Baker.

It was Baker’s ability to project his vulnerability in a neutral, almost pure form, through his trumpet and his voice, that made him fascinating. Most popular musicians project a particular voice, project their personality onto the listener. Baker drew his listeners in, allowed them a space to fantasize.

As people stared at the cover and listened to Baker’s blank slate of a voice, they projected all kinds of fantasies onto him. They imagined a wounded child in need of mothering, a seductive devil luring them into trouble, a dark prophet of doom or the ultimate soulful male. Baker could sound as intimate as if he were whispering in someone’s ear, or so distant that he might as well have not been there at all.

Whether you are familiar with Baker’s music or not, Gavin’s Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker, is a gripping, harrowing, inspiring read, and stands uncontested as the definitive Chet Baker biography. If you’re not familiar with Baker, or all you know is “My Funny Valentine”, give a listen to some of these deep cuts.

“Line for Lyons.” San Francisco, 1950. Baker and Mulligan making a splash by spearheading the “California sound,” cooler and laid back than frenetic East Coast bop. You can almost smell the suntan lotion.

“Chippyn’.” California, 1956. Classic Baker track about “chippyn’,” the slang term for shooting heroin.

“So Che Ti Perdero.” 1962, Italy. Baker recorded this track with Ennio Morricone, who would later go onto to compose the soundtrack for The Good, The Bad And The Ugly, among many other classic films.

Tromba Fredda. 1963, Italy. A strange, intriguing surrealist film.

“Evil Ways.” Los Angeles, 1970. Here’s where things get strange. Trying to make a comeback in the late ’60s, Baker recorded Blood, Chet and Tears, an album of covers. Slightly cheesy, but Baker really finds his legs on the solo in the outro.

“Broken Wing.” Copenhagen, 1985. Baker enjoyed a late flower, with several estimable albums recorded on late tours, including this one. Slightly reserved, perhaps, but soulful.

—Stephan Delbos