[Read Derek Mahon’s “The Snow Party“]

The Snow Party’ is the title poem of a collection Derek Mahon published in 1975. As a second generation Irish kid born and brought up in the South of England, I had first started to write my own poems at more or less the same time, a period in which a remarkable flowering of poetic activity in Northern Ireland had coincided with the renewal of ‘The Troubles’. I doubt that I will ever again capture the eagerness with which I anticipated each new collection by Heaney, Mahon, Montague, Longley, or the excitement of my own first poems being published in Irish journals such as The Honest Ulsterman, Cyphers, and The Irish Press. There was, I suppose, a kind of perverse pride in getting published in Ireland when I couldn’t in England, but added to that was the satisfaction of seeing the names of these same journals included in the Acknowledgements pages of the collections I was devouring.

It was Heaney who first showed me the way, when I saw that the holidays I had spent in rural Mayo could be the raw material for poems. However, over time, I felt that there was something bogus about the Irishness espoused by myself and my siblings. It seemed we were slightly over-egging the cake and had become more ‘Irish than the Irish.’ After all, we didn’t speak like our cousins, who thought we were Cockneys. We didn’t learn the Irish language in school. We didn’t even have an obviously Irish name. Moreover, increasingly, there was also the question of Irish history. My maternal grandfather, Peter McManus, had been 28 years old at the time of the Easter Rising. A young man in his prime, he had relished the opportunity to fight for his country’s independence. He was a great repository of patriotic lore and legend. However, when by the early 70s we found ourselves in the depths of seemingly endless sectarian violence, his view of history seemed simplistic and rose-tinted. All of which brings me back to Derek Mahon’s ‘The Snow Party.

Set in 17th Century Japan, its protagonist is Bashō, a zen poet who wrote a book of travel sketches, The Narrow Road to the Deep North. Mahon’s poem is clearly influenced by Japanese poetic forms. It consists of eight short tercets which look like a sequence of haikus, but without the strict syllable count. Each line tends to be based on two main stresses with some lines having three or only one. The opening tercet sets the scene with admirable concision. Then, almost immediately, we find ourselves in a world of etiquette and refinement where there is ‘tinkling china’, ‘tea into china’ and ‘introductions’. Once the formalities are over the reader and the other protagonists become involved in an experience of pure aestheticism as ‘everyone / Crowds to the window / to watch the falling snow.’ Mahon has always been an intensely intertextual poet and here there are inescapable echoes of Louis MacNeice’s ‘Snow’ and the final image of James Joyce’s great story ‘The Dead’. In the fourth and fifth tercets the poet beautifully captures the snow falling ‘like leaves on the cold sea’ with an exemplary minimalism.

However, in the sixth tercet the mood suddenly changes with Mahon’s finely judged use of the word ‘elsewhere’. Geographically vague, it is nevertheless strongly contrastive. Evoking ‘the witches and heretics / in the boiling squares’, Mahon brilliantly achieves two things. First of all, there is a gruesome contrast between two kinds of spectacle and two kinds of audience. Then Mahon takes the opportunity in this highly circumscribed form to conflate 17th Century Japan with contemporary Ireland, whose conflict can be traced back to the European wars of religion. Memorializing the unnamed victims of history: ‘Thousand have died since dawn / In the service / Of barbarous kings’, he then concludes by bringing us back to aestheticism and, ultimately, silence.

Whether the silence mentioned here is an echo of Heaney’s impatient ‘Whatever you say say nothing’ is not entirely clear and there are other poems by Mahon in which he seems to take himself to task for turning his back on his home and not living it ‘bomb by bomb’. Perhaps Mahon agrees with W.H. Auden’s famous assertion that ‘poetry makes nothing happen’. Is he embracing political quietism or criticising artistic self indulgence? Is he merely attempting to reconcile the two conflicting impulses he detects within himself? What is certainly clear is that ‘The Snow Party’ is a minor masterpiece in which Mahon has gained maximum effect from minimum means by developing one central image. It is also testimony to how, at his best, he has a flawless ear for cadences and the way that vowels, consonants and syllables combine to create the music of poetry.

____________________________________________________________________

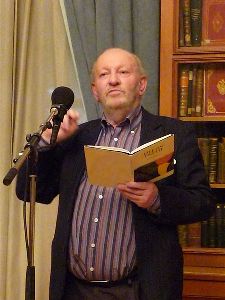

DAVID COOKE won a Gregory Award in 1977 and published Brueghel’s Dancers in 1984, but then stopped writing for twenty years. A retrospective collection, In the Distance, was published last year by Night Publishing. A new collection, Work Horses, has just been published by Ward Wood Publishing. He has published poetry, translations and reviews in many journals such as Ambit, Agenda, The Bow Wow Shop, Critical Quarterly, The London Magazine, Magma, The North, Poetry Ireland Review, Poetry London, Poetry Salzburg Review, The Reader, The Shop and Stand and The Use of English.

DAVID COOKE won a Gregory Award in 1977 and published Brueghel’s Dancers in 1984, but then stopped writing for twenty years. A retrospective collection, In the Distance, was published last year by Night Publishing. A new collection, Work Horses, has just been published by Ward Wood Publishing. He has published poetry, translations and reviews in many journals such as Ambit, Agenda, The Bow Wow Shop, Critical Quarterly, The London Magazine, Magma, The North, Poetry Ireland Review, Poetry London, Poetry Salzburg Review, The Reader, The Shop and Stand and The Use of English.

____________________________________________________________________