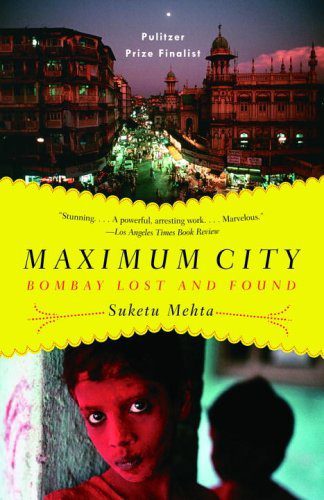

Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found

By Suketu Mehta

Penguin, 2004

Eight years ago, Suketu Mehta published one of the great books about Mumbai (née Bombay). Today, Maximum City stands as one of the great urban narratives of any city. Part memoir, part investigative journalism, Maximum City is as engrossing as it is insightful, and as absorbing as any novel.

Eight years ago, Suketu Mehta published one of the great books about Mumbai (née Bombay). Today, Maximum City stands as one of the great urban narratives of any city. Part memoir, part investigative journalism, Maximum City is as engrossing as it is insightful, and as absorbing as any novel.

Born in Calcutta in 1963, Mehta moved to Bombay, as it was called then, as a toddler, and nine years later moved to New York. Growing up between worlds, Mehta, an investigative journalist, returned frequently to Bombay to report on it, finally moving back, with his entire family in tow, in 1998. Mumbai, as it had since been renamed, was a turbulent city of massive proportions; a city of incredible diversity marred by complex sectarian strife; a city of incredible poverty co-existing with astounding wealth; a city with so many people packed together that it defies its own boundaries; a city so complexly human it becomes a metaphor for humanity itself.

“There will soon be more people living in the city of Bombay than on the continent of Australia,” Mehta writes. “Urbs Prima in Indis reads the plaque outside the Gateway of India. It is also the Urbs Prima in Mundis, at least in one area, the first test of the vitality of a city: the number of people living in it. With fourteen million people, Bombay is the biggest city on the planet of a race of city dwellers. Bombay is the future of urban civilization on the planet. God help us.”

Any reader, having been to Mumbai or not, will no doubt locate elements of her own city within Mehta’s Bombay. Even the extremes of India’s corruption and bureaucracy seem somehow familiar; an identifiable, if exaggerated, version of the hurdles anyone living in a large urban environment, or anyone dealing with a large, top heavy government, faces at one point or another.

“India is the Country of No,” writes Mehta. “That ‘no’ is your test. You have to get past it. It is India’s Great Wall; it keeps out foreign invaders. Pursuing it energetically and vanquishing it is your challenge.”

Reading the following passage, my mind flipped through images of my own nightmare encounters with bureaucracy: the pitiless clerks at the DMV in Washington, DC; the Kafkesque logic of the officials at the Czech Foreign Police; the U.S. border patrol and customs agents at JFK; the visa officials at the Chinese embassy. The list is endless:

“Can I get a gas connection?”

“No.”

“Can I get a phone?”

“No.”

“Can I get a school for my child?”

“I’m afraid it is not possible.”

“Have my parcels arrived from America?”

“I don’t know.”

“Can you find out?”

“No.”

“Can I get a railway reservation?”

“No.”

By avoiding hyperbolic language, Mehta lets the madness of the city – and those who run it, in various ways and capacities – speak for itself. He interviews thugs, criminals, politicians, celebrities, aid workers, activists, community organizers, even the plumber responsible for the flow of water in the chaos that is his apartment building. He provides remarkable insight into what it means to live in a city like Mumbai – and in a country like India – and how dependent that meaning is on one’s origin and status. He writes about the pride of family members who Skype relatives in Chicago or Cleveland to show off their success, only to be defeated by the sight of their relatives’ massive duplex houses and second cars.

He writes about the snobbery that exists at every level, even among the servant classes: there is the live-in maid who won’t clean the floors; the maid who only cleans floors but will not clean the bathrooms; the maid who cleans the bathroom but will not touch the toilet; the driver who will wait in the car but will not open the gate. No wonder, he observes, there are so many servants in India: “We have no choice but to live rich, if we are to live at all.” The greatest character of all, of course, is the city itself, a great, gleaming, filthy jewel in which every human impulse seems to be expressed at once.

But he spends most of his time in the underworld, the realm of thugs and politicians. Of course, to talk about the power of underworld figures in Bombay is misleading. In fact, to talk about underworld figures at all is misleading. The whole framework is upside-down. The familiar power structures are either inflated or inverted. There is word in India for the kind of hand-me-down power that anyone, no matter their social station, can have: Powertoni. When interviewing a low-level member of the Shiv sena, a political party founded by Bal Thackery and one of Bombay’s main political forces, Mehta finally learns the true meaning of powertoni:

“The ministers are ours. The police are in our hands. If anything happens to me, the minister calls …. We have powertoni,” the man explained. “He repeated the word a few times. … Then I realized what the word was: a contraction of power of attorney, the awesome ability to act on someone else’s behalf or to have others do your bidding, to sign documents, release wanted criminals, cure illnesses, get people killed. Powertoni: A power that does not originate in yourself; a power you are holding on somebody else’s behalf. It is the only kind of power a politician has: a power of attorney ceded to him by the voter. Democracy is about the exercise, legitimate or otherwise, of this powertoni.”

Mehta’s powertoni is as a translator of the city, an interpreter of the absurd, and a guide into what, I have no doubt, is the future of urban civilization on the planet. God help us.

– JM