SOME VERY POPULAR SONGS

– Translated from German by Mark Terrill

for example cows beneath the moon,

peaceful souls, ruminating,

Buddha-guts in the high grass,

hidden between small trees and

clumps of brush in the constant

greenness, a practical black-and-white-

spotted metaphysics, tormented by

summer flies which stick to their

saliva. The space hangs inside

their eyes like a gong, which

beckons to the slaughterhouse. Or a

blue rain barrel in the south, where

the sky is an endless continuation

of blue, hallucinated spaces

during the day, but real. The tricks

of the Rolling Stones are over.

I listen to Leonard Cohen singing,

there is a war between the men

and the women, why don’t you come

on back to the war, it’s just be-

ginning. Various grasses grow

along the edges, enchanted

green. The grass is moved, moves

itself, and all the years came, like

always, one after the other: good-

bye, fast cloud, goodbye

blue sky in the window frames, good-

bye, dried grass,

naked in the first twilight,

goodbye. A wet barbed

wire fence stands there, crooked posts,

goodbye, suburbs, as though

no one lives there, fragments of

biographies and newspapers, the

senseless waving. Some lines are

like the waving of children from a

train window while passing through

strange cities in the afternoon, passing

the rows of low-rent apartments with the

single faces at the windows:

if all the confessions in the world

that were ever given and written down

in the courts of the world

were put together and

dragged by one after the other, what

an endless misery it would be

to be in the world. Someone

calls, dials any old

number, and I hear only

their breath, and there again is

the distance, the soft

crackling noise of the

confusion in another

place, and otherwise nothing there

in the afternoon. And in the morning, when

you get up and stare at the hotel

breakfast and you don’t understand

why you’re in this hotel room,

where you actually are, and you think

about what you can do at eight in the morning

after an almost sleepless night,

and nothing else comes to mind except

to take the three dirty shirts to

the laundry, having already

showered at seven, do you

embrace the morning light at nine?

Or do you say, goodbye, morning

light? And then you hear the rush

of a flushing toilet while you

walk along a long hallway and what

do you feel then? That everything is

in order? At ten someone calls and

talks about death, and you make a

joke about the film projectionist with cancer

who’s been with the company for 25

years, and whoever else is in the room

laughs as well. Who goes through the rooms,

unfamiliar, and remembers the lines

from the song: Green leaves, how are

you alone? What sort of damned lonely

business letters are being written.

The signatures don’t matter at all.

And you sing your song, “Lady, I’m

out of here!” That also belongs to the popular

songs. The peaceful Buddha-souls

lie spotted black-and-white in the

greenness. They chew beneath the same

light the soft green grass again.

2. (for H.S.)

Where the ruble disintegrates into single

kopecks, or the dollar into cents,

or the D-mark into pfennigs like

guilders, where the lira disintegrates

like the franc into centimes and the

English pound into the cheap tobacco of

Spanish coins, where the ostmark

breaks into eye-wrinkles and a

tractor stands in the candlelight, where the

Swedish öre disintegrates into insurance

like world empires, where the sturgeon

dies in the rivers and the herring

in the North Sea, where the distances

between the cities grow like the

disintegration among the single cities,

where the yen is changed into the cruzeiro,

where too much is invested in soap,

where the Bulgarian tin cans

are converted into Argentinean bank

drafts, disintegrating like the Finnish

currency, where forests are rafted

down the rivers, where bone meal

becomes plastic, where sums are

copied, where the geese become zlotys

and are frozen in black aspic,

where the dinar drives the camel, the

corn rots in the fields, decaying

like teeth which will be exchanged, where the

peso dies miserably, the black underwear

rises, disintegrating like revenue stamps into

whichever sort of coins the faces may disintegrate,

into whatever bodily needs, piss, dirt paths, rest

rooms and bed sheets, where the army is

financing the study of poetry, where the

technical institutes explain the world,

the twitching heart of a turtle

hanging from a thread for all to see,

where the licenses set the limits, decomposing

into animal-pictures, where signatures are

needed, testaments, accounts, where the bank

holidays are there for a sigh of relief, to hang

out the flags and decorate the day,

where the carbide stank, where the bottles burst,

where the rubble lay strewn and the tattoos,

the companies proliferate like the mass media,

the chunks of stone and rubble have been

cleared aside, the pain and the sorrow

sold off, decomposed into monthly wages,

where there is still something to do, the specter

of unemployment drives them together,

the ghosts of the owners, the ghosts

of the employees, where all of them are busy

administering this world, or what they consider

to be this world, traps, driven together

in the offices, but the offices disintegrate,

where the rooms have many doors and glass

walls, the elevator shafts disintegrate, the

arcades disintegrate, smashed store

windows, mold spores, wild

vegetation, in between store-window

mannequins, rats scurrying through

long ruined arcades, rats in the

pale empty corridors of the skyscrapers,

where the last cripples are still being

driven together, everyone driven together

to administrate this world, these walls,

cyclone fences, entrances, the class-

rooms like ruined swimming pools,

like signatures which disintegrate, where

nights the children scream in the

apartment towers, dismally bound

to the silence, where the children throw up

their baby food again, where the bodies

lie next to each other in the darkness and

masturbate in order to go to sleep,

finally exhausted and empty, decomposing

like the face of a television announcer

in the half-insane dream, who makes new

announcements in different voices like on

scratched records, disintegrating

like shillings, where the twisted

pain becomes jokes in a dialect,

applauded by the ranks, where the ranks

finally disintegrate, where a radio announcer

pulls her tampon out of the hairy hole

between her legs on the toilet in the office

of the National Public Radio during a

pause in which poems are read, where the

Sundays are endless, decayed like sick

lungs, where it is said, that is not

your face, that is not your face,

where the coins disintegrate into faces, old

faces, dead faces, grieved and

hideous on the banknotes which disintegrate,

where we go, simple daylight sparkles

in the rain puddles, sparkles in the

dripping trees, pleasure, the astonishment

of the eyes, when you laughed as you

saw your trailer, the beautiful laughter

of a total lack of understanding as you opened

the car door, where the checks corroded

the surroundings, paper disintegrated into nickel,

decayed like a currency made from black

dream-slag, which crumbles at the

next touch, where a woman has no

other chance than forward through the

bushes, like Bolivar disintegrating into

centimos, where maybe you’re in a dream,

it’s time that we tell each other more

stories, where one doesn’t stand with their back

to the wall, but rather in an open door, in

the daylight, which doesn’t disintegrate like the

wavy plateau with the lethargic chicken hawks

circling above, quiet black movements, clear

in the air, where the sky no longer

fits in the picture and together with the clouds

passes by in the window. Who’s calling through

the frozen forests? Who’s wandering through

the snowed-in halls? Who’s freezing

and huddled together in the endless

transfer station, where the rupees disintegrate,

changed into dirhams, faces upon them,

theories of probability, dog bones,

death a white apparition in a

white invisible tent, Jeep tracks with

dust clouds trailing behind,

death is a dried-up camel

skeleton by the wayside, death is a

dead skunk on the highway, death

is a dead cat on an empty

parking lot, death is the long

rows of suits on the chromed

rack in the next men’s department,

death is a chopped down

tree, where the shadow-shoes lie, worn

out, where the houses have no

walls anymore, where the electric lights

wander about in the rooms, nuclear decay,

multiplication, optical lenses, behind the

frost patterns on the window the book is shut

and a face cries, a brain is

opened, the exhilaration of a dark, clear

winter night is illuminated by constellations

and does not fall, where death is a dried-

up river bed, white gravel

and the plateaus fly by, you see that,

we saw them spread out, the plateaus,

flying by white in the headlights,

I went back into the hastily constructed

apartment, the dreams continuing, the plateau

white, I stared into the aluminum pot,

at the rest of the broccoli under the light,

the plateau passing by, white, with the

slight indication that we make, where a

dirty, rickety claw is a clean

hand stroking a mahogany

table, having plundered the many

daydreams, now it lies rickety and

crooked on the clean surface, where the

Luxembourgean francs become Malian

dollars, which disintegrate into Cuban pesos,

who is it who shits out money and lets a forest

die so that he can appear in the comics,

massaged on the beach, he with the mantraps

and self-inflicted gunshots, observed by helicopters,

a marked man, who is it who drags their suitcase

through the bus station, who is it who drops a coin

into the TV automat, who is it who skims the

psychoanalytical journals in order

to solve a case, who is it who interprets

the world, who is it who interprets the next construction-

site fence, who is it who interprets the apartment,

shadows of people burned into the

asphalt, stones with human shadows

on exhibit, aerial photographs of the

landscape allowed for postcard greetings

by the Minister of War, he who allows, believes

he has the rights for fencing in,

where the piastres are scrap, poetry is

not a waiting room where one stays overnight, tired,

behind a newspaper opened to the

swarming masses of war, every word is

war, scrap-words like death, driven

together in herds, without differences,

should I have slept with your wife,

should I have had more magazines,

should I have used the dish-

washer, should I have followed the movie

posters, filigree-gray hypothetical questions,

tendrils, cement ornamentation, where the dreams

die off like plateaus, a canister on the

shark, the daily view out the

window into this side street, which you

don’t know, where the dollar disintegrates

into kopecks and the ruble into cents, where

pesetas are wrung from the bones,

but the pleasure is greater than the

sorrow, the drachma is smaller than the

lust, reduced to a hundred lepta, which

disappear at the next opportunity,

where the Turkish pounds are extracted from

the tendons, decayed, decayed in the buildings

of the 19th & 20th centuries in West Germany,

extensions, bills, obligations, everything

the same, pawned off, worn out, trashed,

pawned off again on television, from the

serial, from the jukebox. Gentle face,

in the middle of the crowd you’ve seen

the twitching body, suddenly the

concert was over, did you stammer, did

you cry, where the corridors are cement,

where the speaker boxes boomed, where the faces

broke into dream-wrinkles, where the city maps

have white spots, where the color white in no way

means death, where the dog fur fails to warm,

where the ways end, Ivory Coast is a

fantastic name, tattoos,

scars, moving in, moving out, many thanks.

3. (History)

Last night I was thinking about the love

story of Adolf Hitler.

I saw the permanent waves in the hair

of Eva Braun. How many German women

today look like the smile of

Eva Braun. The photos reproduce themselves.

I was not, I know, born in a

photograph. Snow fell in April,

as I was born, shrouded in the

ornamental cloth of the baptism ritual.

The war, I don’t understand what that

is, which language is where? Eva Braun

smiled at Adolf Hitler, that was in

Berlin. What did Adolf Hitler first say

to Eva Braun? Which distances

exist between the permanent waves on the

photo and the old fashioned curling iron

for permanent waves which I saw later

on a windowsill? As I slept in the Academy

of Art in Berlin, I thought about

this curling iron for permanent waves.

The photo was a memory which I looked

at. Twenty years later I looked

at a fat face in the daily

paper, which drank ersatz coffee in a Berlin

hotel from a hotel coffee cup, the title was

Professor, the title was not to be identi-

fied. Eva Braun, was your neck shaved?

Eva Braun, what did you think about the Sarotti

chocolates? Adolf Hitler, as you went through

Munich with your Pelikan watercolors, what did you

see? The Sütterlin script ruined the

handwriting. From the handwriting I was supposed

to learn. Adolf Hitler skimmed over the city

maps. Eva Braun looked in the crystal

mirror at her cunt. Which size

did your thighs have, Eva Braun? I know girls

who look exactly like the Eva Braun who looks

like Eva Braun in the photo. I grew

up, considered my pubic hairs, considered

nipples, considered the reeds, years

later I considered the picture of Eva Braun.

In the same month a breast of the

wife of the American president would be

cut off, in another historical

photo old men polished their assholes

on brocade-lined armchairs after

the conference, the southern afternoon is full of

junk, dust, crumbling constructions. What was

with the intestinal worms which Adolf Hitler’s German

shepherd had? What was with Eva Braun? A

storybook story which one suppressed

like years later the interpretations, ended.

Half of Austria arrived in a train,

kissed Eva Braun’s hand, looked at her tits,

sealed with permanent waves. Adolf Hitler

passed out postcards. I saw my

mother in a photo in a long row

sitting and laughing, I saw my father

in a photo going along a tree-lined avenue,

naive in uniform like an avenue tree,

what were they playing as they were

photographed? I saw the creases in the pants

of Adolf Hitler in a photo, I saw, four years

old, a dark train station passing

by in 1944, I saw an enameled sign

with blue and yellow wool and knitting needles

on the red brick wall of a train station,

Eva Braun, did Adolf Hitler tenderly stroke

your pussy with his tongue? Adolf

Hitler, did Eva tenderly suck your

cock? Or was that taboo thanks to

the state and politics? Come stains on the winter

coat, a couple of generals in the toilet,

they drew battle plans on the shitty

wall, named names, heights, deployments,

Eva Braun, what did you feel when you

got the capsule? Did you simply think

you’d had your chance? Did you think,

now I’ve had it? And the teeth of the German shepherd

fell out of his jaw after the strong injection.

The orgasm of death is cheaper than the

orgasm of life, although it’s questionable whether

the orgasm of death isn’t simply pent up

life that explodes. Why isn’t life

in the multitudes every day?

Why permanent waves, Eva Braun?

Why are you smiling, Eva Braun? Why

do you take cough syrup, Eva Braun? Didn’t Adolf

Hitler know that the Austrian

psychoanalysis, lying in the sentences, lies? I

was never at the river Inn, also

have no desire to look at the water,

also have no desire to look at the water in Cologne,

dead water, full of dead fish and

plants, dead water, which they fought over, borders,

coals, fires for the industry, furnaces, embers

in the night, dancing figures before the open

fires of the industrial complexes, no holy saint swims

in these dead waters, no holy saint spits

out the apartment window, the crude passing through

is better than taking pills, the patents,

Eva Braun, how was it for you under the shower,

German charcoal, flamingo flowers, Spanish irises

and pails? Adolf Hitler in a nightshirt,

in the cement, under the earth’s surface,

sparkle of nerves, dancing over the

files, he dreamed madly in the cement bunker,

supposedly never hit anyone

personally, he had others enough to do

his hitting, there are always others who

sign, hit, hang, indeed there are

always others, employees, secretaries,

office boys, insanity, Eva Braun, you straw puppet,

smoke, cyanide, trace elements, signatures,

which suddenly become single living

persons, things, the shabby things, they’re

standing in the room. Did Adolf Hitler stand before you

in the room with a stiff cock, Eva Braun? Who washed

your bra, Eva Braun? Did you think about

Persil laundry soap? World history in the form of

industrial comics, Eva Braun, a lace dress in the

large hall, among the human voices, shoulders

lifted high, did you see them? What’s with

the dyed hair? What’s with that old high

German? What’s with the fossilized

love stories? Word-ghosts, dirty bastards

of history, stumbling through the rhymes,

between the film-shadows of Berlin, shadow

gestures, projection-screen-shadows, shadow-screams,

collapsing shadows, later accompanied

by a soundtrack, synchronised

lip movements, Eva Braun, in which

magazines were you reading? I have to remember:

my mother loved airplanes and ghosts,

which reappeared, phantoms, she dreamed of them,

even before she cooked for the men at the

airfield, in her odd French, my

father borrowed a car in his school-English,

the top rolled back, they

stopped in the countryside, they fucked

at the edge of a warm yellow wheat field in July.

My mother loved cheap paperbacks, she looked

to see if the seam in her stockings was straight, she went

across the meadow in a silky shimmering dress.

The father-in-law left his library to the

state of Israel for a sentimental reason,

and what happened before, that these forms

developed, more sentimental than the memory

of house-corners and street names? More sentimental

than permanent waves in a photo? I have to

remember the pale suburban settlement, I

have to think about the truck that

suddenly stopped in front of the house, packed with

people and their belongings, billets to make

the foreignness even foreigner, checked off

the lists, bedpans, briefcases, pomaded and

parted, they had nothing, owned the in-

sanity of never-owned imaginary goods, if they

spoke, from where they came, the biographies ruined

by dead Austria, old myths, fallow fields,

the opposite is not the industry, the oppo-

site disappears in the old photos, in which

history disintegrated all around, Eva Braun, opaque

window glass, portals, coma in a Swedish

hotel room, shots in the leg above the stocking

garter. Now the computers are tossing bones

in the air, Stanley Kubrick, the film trick

is revealed, despite four-channel-stereo in

the red-plush cinemas of Soho, where I am one

rainy evening, walking through London alone, quiet,

collected, in the light gray, windy

February evening, decaying London, elegiac

West End streets, elegiac advertisements, elegiac

theater buildings and striptease clubs, elegiac

filthy book stores under aged,

murky dust, rusted leaky water pipes along

the house fronts, a senselessly ringing alarm

on a house wall, dismally yellowed paint,

entrances with the names of bodily flesh,

which for a few moments can be bought,

contact between a lonely cock and

a cold cunt before the weak gas heater of

the rented room, miserable and lost in the

maze of numbers, bleak and frozen in the money.

Eva Braun, who wrote you postcards?

Eva Braun, have you ever stood freezing in

Piccadilly? Eva Braun, what did you say in the moment

when that photo was taken? After the movie I crawl

shivering under the thin blanket of a cheap

hotel in Bayswater, Odeon station, the monster

quarter of London, crumbling courtyards, buried

bodies, the gas-fired fireplace doesn’t heat, the

wallpaper is stained, I read a few more

poems by Frank O’Hara and W.C. Williams, I

drink the rest of some cold coffee out of

the paper cup that stands on the marble mantle

over the fireplace, I’m alone in these American

poems and see myself in them in the middle of this

London night, yellow fog lights along the

streets, Victorian monster-columns and portals

the whole street long, windows patched with cardboard,

curtain-scraps, and suddenly, in the silence, completely

crazy, I remember the call sign

of the BBC radio one morning during the war. I

remember the after-the-war-chocolate of

the English soldiers, blue plums on a

cart, which was being pushed through a courtyard,

Strauss waltzes, a dark movie theater and war.

A bone tossed in the air, a killer’s

tool on the white screen of the memory,

a flickering shadow, hidden behind ornamental flowers,

together with the shadow-noises from the stereo speakers

is nothing but a shadow in the eerie, insane

ballroom of Death, which is the air, Death blows

bubbles in the air, it’s much better to relax

peacefully with a liverwurst sandwich during

the lunch break, better to eat the plums out

of the icebox without saying you’re sorry,

better to drink cold coffee from a paper cup

in a hotel room at night, better than

moving pictures, aerial photographs, Eva Braun, I’m

thinking here in this Cologne night, stuffy and dismal,

while I look at a photo, which tells of the love

story, kitschy and hand-colored,

Eva Braun, little monster among

the decor, smiling stupid and sad

in the photo, and before the photo was taken,

really. The eyebrows are

touched up, your mouth is open, lipstick

on the lips, are the stocking seams straight? Are you

wearing a flowered dress? Has someone

messed up your hair? What’s with the accent? Did

someone give you a horny look, your slightly fat baby

face? Have you forgotten your cunt? Did your

cunt dry up out of fear as the war began?

Berlin sky, as I flew in with a Pan Am plane,

I first saw a cemetery between

the houses, the gentlemen laid their

newspapers on the empty seats,

the taxi driver swore about the passers-by as

the lights went on. In the subway hall

someone held their bloody, dripping face between

their hands and turned toward the tiled wall

as the automatic doors slammed

shut. Did you mend your stockings with

Güterman’s silk thread? How did you look in

a swimsuit? Did you shave your armpits?

Shaved armpits always look like soap

and deodorant, stubbly and slick.

Fantasy has taken over the industry

with its employees.

Did you eat a liverwurst

sandwich? Did the liverwurst sandwich taste good?

Did Adolf Hitler have sweaty feet? Did he kiss your hand?

Did he talk in his sleep? What did you take

against the headaches? What did you think

as you were chauffeured along the Kurfürstendamm?

In the fading shadows of 5 in the morning

I sit there between the folded up,

locked up patio chairs and tables, smoke

kif in the shadow of the Café Kranzler awning and walk

through the tear gas clouds and shards of glass

from the shattered storefront windows, the whores

having hastily retreated as the street battle began

a few hours ago, then I take the first subway

train to the Wannsee, where a couple of swans are rocking

between the garbage along the shore, a lifeless pier,

a weak dawn, light gray. What kind of

fur coat did you wear? What kind of toothpaste

did you use? I tremble in the first dawn

in Berlin, take the socks from the radiator,

let down the shades. It’s a pity

that you didn’t invent love, Eva Braun.

I write this rock ‘n’ roll song about your

terrible insanity, Eva Braun. Would you have

liked this song? Would you have sweated as you danced?

What did you talk about as you were alone in the cement

bunker? Why the color brown? What did the tongue demand?

No one loved Adolf Hitler, and that was why he

had to win the war? Did you see the bodies?

Did you see the hand-to-hand combat? Did you see the

flame-throwers? Did you see the burned faces?

Did you see the gas-cripples? Did you

see the killer-virus spores? Did you see the

flower-shadows? Did you

look out the window? Did you turn off

the nightstand lamp? The permanent waves of

order on your head, your fat, bare

shoulder, your underwear from the department store,

your pierced ear lobe for the jewel, your

handkerchief with the mucous, the camellia

between the legs, your ass-shapes in the

garter belt, your nipples, will they remain a

secret? In the middle of the historical showplaces

of the war, the war is a showplace, who even

looks? Is a love story necessary that needs

so many questions? Now you’ve disappeared in the

historical photo. Now the disguises are going

around. Now the story is broken down and over.

4. (D-Train)

: letting the newspaper

flutter out the rolled down window,

a child’s hand, with the

shreds of paper against it,

the misery (foreign countries), which invests in this

country, sits on every

furtively glanced-at

street corner, sad, tired faces,

without expression, bags under the eyes, lines around

the tight-lipped mouth,

a young woman cries from exhaustion

in a two-and-a-half room apartment, in the

unfolded architecture of geometry,

it’s night and the heating pipes are ticking,

Quote: “The most dangerous animal that exists is

the architect. He has destroyed more than the war.”

Hair loss following birth, fear

on the street, in the middle of the day, if one stands

still, surrounded by the multitudes, the absent

glances, waking up, coughing & spitting

in the sink, postponed material circumstances,

the delicate bodies pushed up against the walls by

the cars, the same rows of suburban streets

all the way into the inner city,

single, running bodies between the

convoys of the auto industry, blurred figures

behind the dirt-flecked security glass windows, smaller

than their own bodies in the industrial shells,

the newspaper rips in the headwind,

shreds of paper drift over the narrow gardens

along the tracks, kites made of stinky

printer’s ink, collages of the

daily gradual madness,

frozen swirls of words: brand names,

reptile brains, hate, slander, semantics, the

big families continue on. In the streets

the skinny girls’ bodies, bones with a little

skin over them, in colorful rags from the second-hand store,

“when the music’s over” between the rain-

faded old advertisements, (neon-light

extinguished curiosity to live, calligraphy)

extinguished poetry. The dawns

are damp and impassable, masses of bent-over

figures, they disappear in the offices, they go

into the stores, they have to go to schools, kindergartens,

their ways of life distinctive between

rows of products and shelves, in the pestilent-light-flicker

of the TV at night the faces of the politicians appear

and discuss, in the pestilent-light-flicker

of the TV the strange faces appear

on the wall of the room: do you remember

“until the end” the dark house entrances,

in which we stood together,

do you remember your own kisses in the

stairwell, do you remember kisses

at all? (Or what

you felt?) Submerged in the glowing grass

along the paths, seen from the open train window,

we let the newspaper shreds fly.

Yellow afternoon light reflects in the windows

which we pass by, September-yellow

and what kind of country is this,

what kind of thoughts are

thought to the finish here, finally to the end,

the end “the aristocracy

of feelings,” hahahaha, that’s

not to my taste,

if anyone should have anything to do with that at all,

IBM-typewriter-feelings and kisses,

I stretch out my feet, how does that

one over the other, in this fit together?

compartment, the white Converse All

Star basketball shoes, 12 dollars,

on the red plastic seat, and once again the

piece of newspaper torn for the child at the open

train window: how the words fly (masks),

the fragments, it’s one of those gentle afternoons that

we rarely have, light over the pale, monotone

cities, soft afternoon light

on the crumbling facades of the suburbs

and tract homes, soft September-afternoon-light

on the faces in the open windows

which we pass by,

gentle human-faces

in September,

the hate of the newspapers rips, flutters as

paper in the hand, that cheerful

sound in the moving

D-Train: it brings us from the northwest

regions of West Germany through the

zones of industry and profit,

dead, abandoned winding-towers, black

wheels in the air,

slag heaps,

dead roads, black, sooty

steam locomotives on a dead

track, rusted railway lines

& dust-coated Scotch broom along the embankment, do you

really remember your own kisses?

And when the West (“Oh to be out of here,

German industry here where everything went

collapses? as wished except for the new”)

“Here in this land I live!”: do you really

live? (“To be far away

and in a foreign

No, not this country.” E.P.)

sensation.

Until now this was a foreign country, wherever you

look,

Memory: I hear the shaky

The chestnut voice of the poet on a record

tree in the in an apartment, evening,

lightless sinister hallways

narrow courtyard, and without voices, maybe 60 names

on the nameplate in the entryway

still-standing by the glass door, locked early,

elevators, the stairwell light out, a red

glowing light switch at the end of the hall,

the calendar and then in the midst of the lifelessness

picture television film sounds behind a door

on a as I walk along there / the voice of the

office wall, poet stuttering in on a

Sunday morning, and

sun now, after the hallways, in this

blinds, West German apartment years later

suddenly again)

Prone Venus and Coca Cola 1974,

verbs in a continuous chronology,

“this Coca Cola of the entire world”

why do you want to speak nicely?

“Must we be idiots and dream in the

partial obscurities of a dubious mood

in order to be poets?“

(W.C.W.)

Burned out in a beautiful September light, the

personal economy: a total disaster,

is the economy a personal feeling? Contradictions

because I speak, contradictions because I think

about it: notes in the newspaper margin, being torn to

shreds. The few friends scattered about the

suburbs, the new friends strewn singly across the country-

side. Different

voices,

different biographies,

deviations, “good so.”

Discussion: Where everything is forced to connect…

What did you feel

as you touched the naked body

with your lips, what did you

feel in the middle of the trashed

landscape, word-gods,

side-street-sex,

under the arranged machines?

Let me

remember, you say,

let me remember, leave me

alone, you say, leave me, gentle face

in a soft September light,

like now: answer softly

answer, “in the midst of the daily

plundering, or?”

Like the faces in the open afternoon-windows

don’t answer. There is a sheet-metal field, dented,

“valse d’autumn” or how such a feeling is called,

not the clarity of looking out a D-Train window,

gentle, gentle rhythm here now,

let me, let me remember, you say.

Small train stations appear and remain behind,

meaningless structures, : remain behind?

meaningless stops : meaningless?

yellow-red fire

in a scrap yard,

gentle, gentle woods, last remains of

forests in which the thin morning fog

still hangs, traces of dampness, not

bent over, small peaceful ponds, forgotten

at the edge of an estate (:“we’re coming back,”

in that house, we’re coming home, home?) for the eyes

a fugitive rest, from the train window

looking out, the long, slow

even view across this country. There is a

hunkered-down green, fantastic green, which passes by,

and a child’s hand stretched out the train

window.

Why sadness? All: you gentle

faces in the afternoon light (no faces

: you gentle faces between for the coins)

the billboards, you gentle

faces in the window frames,

you gentle faces in the September light, you

gentle faces of West Germany, tired and sad,

you gentle faces, hungry for cunt, cock,

tits, hungry for an exotic everyday

life, hungry for a kiss, hungry

to feel your own kiss between the walls,

hungry between the advertisements, hungry between

the classified ads, hungry between the pictures,

the advertising sales department closes at nine in the evening

the movie theaters are darkened, to show a

little more life, the box offices close a

quarter-hour after the main feature begins,

the television station broadcasts until shortly after

midnight, hungry in the narrow

gardens, hungry for a gentle embrace,

what do you give your selves? What kind of a

horror is that, when one stops in the middle of the street,

standing among the passers-by,

& each for everyone a passer-by.

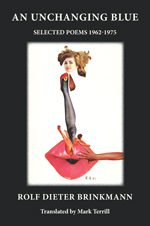

“Some Very Popular Songs” by Rolf Dieter Brinkmann and translated by Mark Terrill from An Unchanging Blue: Selected Poems 1962-1975. Translation (c) 2011 by Parlor Press.

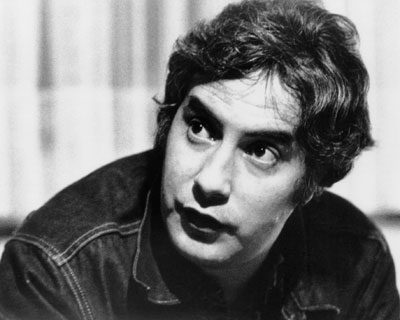

ROLF DIETER BRINKMANN was born in Vechta, Germany, in 1940, in the midst of World War II, and died in 1975, in London, England, after being struck by a hit-and-run driver. During his lifetime, Brinkmann published nine poetry collections, four short story collections, several radio plays, and a highly acclaimed novel. He also edited and translated two important German-language anthologies of contemporary American poetry (primarily Beat and New York School, for which Brinkmann had a particular affinity), and translated Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems into German, as well as a collection of poems by Ted Berrigan, entitled Guillaume Apollinaire ist Tot. In May, 1975, just a few weeks after his death, Brinkmann’s seminal, parameter-expanding poetry collection Westwärts 1 & 2 appeared, which was posthumously awarded the prestigious Petrarca Prize.

Rolf Dieter Brinkmann’s radical poetics was unique in postwar German literature. His primary influences were Gottfried Benn, European modernism and the French nouveau roman. In the 1960s these influences were merged with William Carlos Williams, Frank O’Hara and Ted Berrigan (the latter two of which Brinkmann translated into German). Brinkmann’s strong affiliation with the New American Poetry provided a reverse-angle, cross-cultural perspective on one of the liveliest epochs in American letters, with a decisively German slant. His permanent confrontation with the postwar German literary establishment (reminding one at times of Jack Spicer and his place in American poetry), and his envelope-pushing experiments with language, syntax and semantics (taken to the extreme in Westwärts 1 & 2), led him further and further away from the literary scene. His confrontational nature and volatile personality were feared at readings, and together with his huge creative output and his early death, earned him a reputation as the “James Dean of poetry,” a true enfant terrible of contemporary letters.

An Unchanging Blue provides a generous sampling of translations (with German originals) taken from ten collections of Rolf Dieter Brinkmann’s poetry published between 1962 and 1975. An extensive introduction by Mark Terrill contextualizes Brinkmann’s place in postwar German literature.

About the Translator:

MARK TERRILL was born in Berkeley, California, shipped out of San Francisco as a merchant seaman to the Far East and beyond, studied and spent time with Paul Bowles in Tangier, Morocco, and has lived in Germany since 1984, where he’s worked as a shipyard welder, road manager for rock bands, cook, postal worker and translator. The author of a dozen books and chapbooks, with other writings and translations appearing in more than 500 magazines, journals and anthologies worldwide, he’s received three Pushcart Prize nominations and was included in the anthology Ends & Beginnings (City Lights Review #6), edited by Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Recently he’s performed his work in various venues in Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin and Prague, and was guest-editor for a special German Poetry issue of the Atlanta Review in 2008.