Yannick Desranleau and Chloe Lum live in Montréal and have worked together since 2000. Their collaborative practice has spanned the fields of visual arts, music, and experimental graphic design. Together, they are the creative force behind Séripop, a collaborative duo whose work has been exhibited widely and is part of the permanent collections of galleries and museums across Europe and Canada, notably the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Until 2012, they were also members of the influential avant-rock trio AIDS Wolf.

B O D Y art editor Jessica Mensch caught up with Séripop on Skype to ask them a few questions about their newest projects and find out what life is like after the break up of AIDS Wolf.

B O D Y: Can you tell me about the title of your recent solo show at Galerie Hugues Charbonneau in Montreal, PQ: This Peculiar Bias Will Nonetheless Set Up A Vast Field For The Unforeseen.

Chloe: Well the show itself doesn’t have a title, mostly because we were caught in this giant onslaught of projects in the months leading up to the show, with no brain energy to think of words. Yannick came up with the title of the piece after we were done installing it.

Yannick: The title is about the making of the work itself, where we followed a “directed chance” approach. We each worked more or less on our own side until a certain point. Shortly before we went to install in the gallery we combined the elements we each came up with. We had a generic sketch to follow in-gallery, but the specific placement of each object, or the construction of each combination was decided on the spot. Our main goal was to set up a giant physics experiment by supporting a “roof” with little pillars. Since none of the construction’s details or the specifics of the material’s resistance were clear during the conception or throughout the exhibition period, we expected the whole to react, and we would embrace the final result as the “true work”.

Chloe: This type of improvisation is very outside of how we normally work.

Yannick: Yes, but in a way, a lot of the works we did in the past year had an improvised part in it. They mostly all involved staging various physical reactions for which we couldn’t plan the outcome.

Chloe: But it was more planned improvisation.

Yannick: So, the title is there as a reminder of what guided the conception of the work. Despite how much planning could be done in order to foresee all engineering aspects of the work, by bringing more elements to it and increasing its complexity, it became more and more open to unplanable possibilities. We created this set up in order for the project to have an educational value for us, so we could learn and pick up tricks from “what works” and “defects”. The elements falling into those two categories are actually processed as equals, and taken as conceptual matter from which we can build on. So even a reaction that can be traditionally perceived as a failure is considered as something to explore later. The advantage of working as a duo while following this state of mind is that there are two individual concepts at play in the work. They are both as good as each other, therefore we think it is telling of our work process that chance shapes the end result of a work.

This Peculiar Bias . . . was therefore just pushing the envelope a bit more compared to previous works by including hints at the production process in the finished work, and how all this got revealed by the physical phenomena it displayed. This is in addition to having the installation process being kind of obvious and telling a narrative – which has been a staple in many of our recent works.

Chloe: The lines between the two (production versus installation as performance) are blurred in this case.

B O D Y: This makes me think of your piece Uncountable (Not Comparable) at L’Ecart (2012), and your later installation for Art Souterrain, J’ m’ en suis deja souvenu (2012). They both make formal use of tearing – an improvisational gesture, although in the earlier work, it’s you who does the tearing.

Seripop covered a 17′ x 55′ path of floor at Complexe Guy-Favreau, Montreal, PQ, with a double sided screen print.

Yannick: Yes, This Peculiar Bias… pulls a lot of lessons from Uncountable. . .

Chloe: Uncountable . . . was the first thing we did in a gallery without a clear blueprint.

Yannick: Without getting more site-specific, this work (This Peculiar Bias . . .) involves us more in having to react to it on the spot. I guess we are getting more “painterly” in that effect.

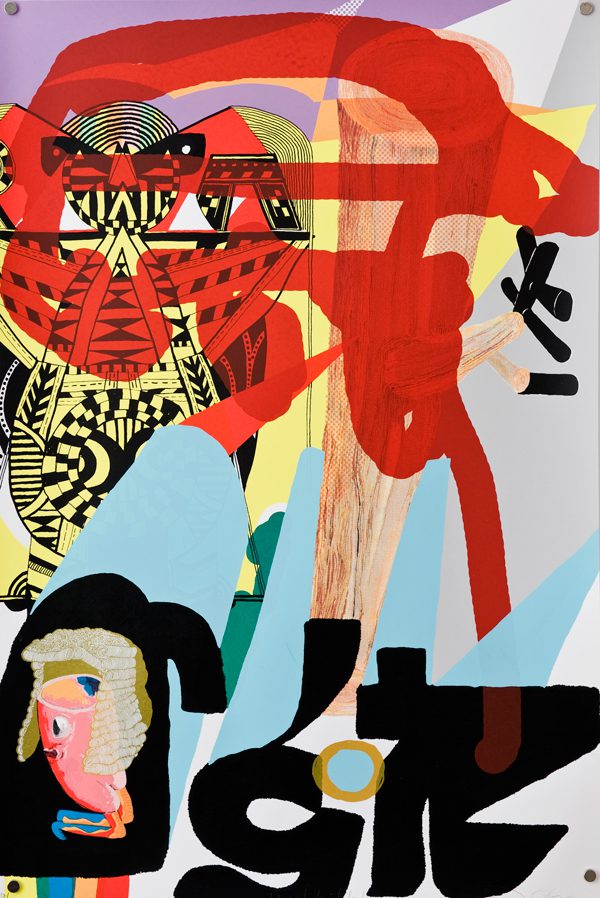

Chloe: I guess we could say it’s site responsive rather than site specific. It’s strange because I never thought of it that way before, but Janet Werner recently told us she saw our work as painting.

.

Yannick: Gesture has entered our visual vocab. I don’t know if that’s good.

B O D Y: Isn’t that what Post Minimalist Sculpture is about – the gesture of the material?

Yannick: It’s way less robotic than that. I don’t think we are trying to romanticize the materials here. I think our latest (work) is more about overtly showing precarity/physical tensions.

Chloe: In Minimalism and Post Minimalism there is also the formal concern of the viewer in the space of the work. I feel our intent is more matter of fact. I’m always ambivalent about the idea of assigning a role to the viewer.

[Our internet connection is lost. Some minutes pass before we resume the interview . . . ]

Yannick: $1885 .00 for an inflatable gorilla.

B O D Y: That’s expensive.

Chloe: No it’s cheap. The gorilla is huge!

B O D Y: Well how big?

Yannick: Well it’s 25 ft high.

B O D Y: Ha hah, you could live in it!

Yannick: Pretty much.

Chloe: We are thinking of getting four of them.

Yannick: That’s a three month rental price. Retail it’s probably $20,000.

B O D Y: What do you want to do with them?

Chloe: Invade downtown Montreal!

Yannick: We are invited to do a temporary public art piece and we are shopping ideas around.

B O D Y: Large inflatables are amazing.

Chloe: As long as it doesn’t blow away and destroy a greenhouse like Paul Mc Carthy’s turd.

B O D Y: Ha hah . . .

I noticed in several of your installations you have sculptural pieces composed of multiple layers of screen printed paper. This layering mostly obscures the screen printed image. This struck me as a strange thing to do.

Chloe: It’s funny because we used to do something similar in our poster work. We’d do really detailed drawings and then just print over them with big blobs of opaque colour.

Yannick: We carry this interest in accumulation/dissimulation from our poster days. Also it is referring to how posters are placed on hoardings. How they accumulate with time. First we wanted to replicate that with the information of the posters themselves, then it just got applied literally in the work through physical means.

B O D Y: By information, you mean the text?

Chloe: Text or drawing. There is also an interest to keep things “moving” so to speak, in long or repeated viewings.

Yannick: Visual and textual info. Graphic and textual.

Chloe: It’s all information. I think we also enjoy courting the perverse by making works destined to fail or decay, keeping a lot of the visual hidden from the viewer is just part of that impulse.

B O D Y: It does feels perverse.

Yannick: At the same time it reveals the tridimensional aspect of paper beyond folding it to “occupy space” or “take volume”, etc. This aspect is something that’s not thought about much, paper is almost always considered immaterial. . . Materiality through bidimensional invasion.

Chloe: Yes while kind of asking the question “what the fuck is art for?”

B O D Y: What do you mean by the tridimensional aspect of paper?

Yannick: Well because it’s so thin it is considered pretty much only for its flat, bi-dimensional self when it has to support an image or communicate something (Almost like the goddam thing is ethereal.) Even painting went beyond that. When you accumulate the sheets-and we are not talking like a book, but more like gluing sheets of paper on a wall, well, it breaks that. In this manner we see possibilities in printmaking . . . in its relation to matter.

B O D Y: Cool.

Chloe: Paper has this bad reputation for being flat when really it’s a super plastic medium that can be used in infinite ways.

B O D Y: It’s interesting thinking about that and your Charbonneau installation, where the paper almost appears to stand alone. Supported only by a few beams of wood . . .

Yannick: And paper balls and chairs and…

B O D Y: Do you disagree?

Yannick: No. What you can’t see in the pictures is this opposition or paradox happening. When you are looking at the piece from outside it’s a closed space, it’s very contained. But when you peek in there, it’s like this new space got created, and it feels like it is expanding forever.

Chloe: And from each vantage point the hidden space is dramatically different.

B O D Y: What is it about decay and failure – common threads in your work, that you’re attracted to?

Yannick: Failure is related to that thread of thought we talked about- this play with chance and undecided outcome. In a way we try to make failure a matter to play and respond with, and this often translates into booby trapping ourselves with our work.

Chloe: It’s also interesting to be in opposition to the archive.

Yannick: There is a will to provoking collisions, but you will never know how it will crash.

Chloe: We make objects but most of them can’t be owned. Failure and decay are both ways of bringing time into the object. The pieces end up as somewhat performative but without the requirements of our bodies or the bodies of the viewers. In that way we can see our works as events.

B O D Y: For many years you were both professional artists and musicians. Is there a comparison between the ideas you explore in your art practice and the music you composed with your band AIDS Wolf?

Yannick: We found similarities between the two projects mostly at a formal level that qualified the performative interplay between the collaborators and the matter. Writing music in AIDS Wolf was a lot about crashing different patterns and sentences together, chance (albeit directed chance), and the superposition of sounds. Our interest in atonality and dissonance translated a bit into our use of color to mark our territory in some of our installation work. The same goes with the loudness of our live performances; creating an immersive space, where abstract, ethereal matter and concepts become physical, or where we use sound/visual strategies to claim the architectural barriers around us.

Chloe: I feel with both we really use the space as a medium. With the band there was a lot of emphasis on letting sounds ring out in space and with using natural feedback, and I think we use those principles visually with our installation work. In both cases we are interested in complexity but also a certain scrappiness.

B O D Y: Does music influence your practice?

Yannick: Music did not influence our practice per say; music and art were always two different things. We have some rather pretty straightforward formal concepts that we apply and experiment with in both disciplines. We are aware of the difficulty of bouncing an idea from music to art and vice versa without falling into clichés, and we really tried to keep both practices isolated from each other. Although, the interdisciplinarity in which we were working had the effect of informing and developing those general concepts that were driving our research in both fields. So, since we are on hiatus from music now, I would say yes, there is certainly a residual influence.

Chloe: I think the main influence we pulled from music into our visual art is that can-do Black Flag- type of work ethic where we have these idiosyncratic projects that we make happen by whatever means necessary. Jammers tend to be highly resourceful people.

B O D Y: What have you been listening to lately?

Yannick: A fair bit of opera: Wagner, Berg, Adams. Death metal and 80’s prog metal. Serial composers, especially pieces that were composed as soundtracks, think Jerry Goldsmith (Planet of the Apes) for instance.

Chloe : Leonard Bernstein, Harry Partch and James Blood Ulmer. Death. I saw Weasel Walter/Mary Halvorson/Peter Evans trio the other night, it was nuts. Lots of tension.