THE LONG HALF-LIVES OF LOVE AND TRAUMA

(an excerpt)

The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma

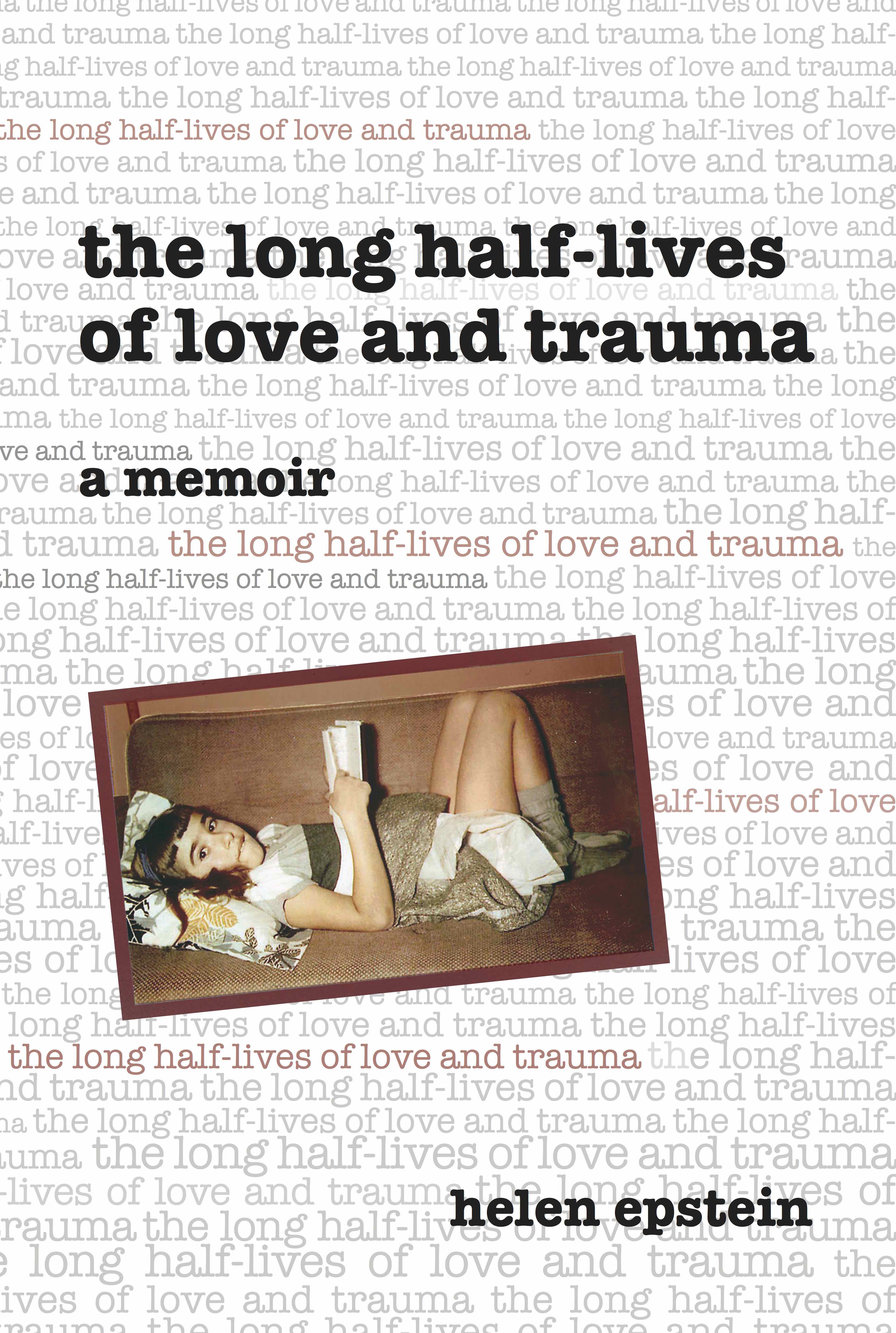

A memoir by Helen Epstein

Published by Plunkett Lake Press

We all carry cameos in our minds: miniature, idealized portraits of those who most deeply touched our lives. Apart from my parents, I carried no portrait more vivid than Robbie’s. I’d had several more intimate friends. I’d lived with men whose bodies I came to know far better than I ever knew his. I had married, given birth, raised two sons with my husband. But throughout it all, like some endlessly looping song, Robbie’s voice and face remained embedded in my being.

What was he exactly? Not a crush or even an authentic boyfriend, but a conflation of caring guides: my chaperone, my teacher, my eventual lover. Robbie had also been my model of the artist I wished to become. From the start, he had been a kind of ghost, appearing at key moments in my life and then disappearing — for over three decades.

I was 15 when we met at our piano teacher’s studio. “Fresh as a peach,” my mother embarrassed me by saying. I didn’t like to be compared to fruit or, as my father said, also in Czech, “a tadpole.” I had always been one of the taller girls in my classes but after puberty I grew to nearly six feet — an uncommon height for a girl in 1963. My breasts grew too, from ironing board flat to what girls called “developed” and boys called “stacked.”

I did what I could to make myself inconspicuous. Where there was a wall or table, I leaned on it. I wore flat-heeled shoes and loose sweaters. I walked quickly, shoulders hunched forward, as if I were hurrying in from the rain.

Maybe if I’d been born in the twenty-first century, I might have seen my body as a source of power. I had friends who did, while I wished I could be invisible. I still sometimes do. When women friends complain about men’s eyes passing over them and moving on, I think: what a relief!

My piano teacher was one of the few men back then who seemed oblivious to my body. For Mr. Labovitz, everything was about the music. I didn’t know about his role in Manhattan’s left- wing community. I wouldn’t have known then what “left-wing” meant. He was my piano teacher; that was all I thought.

“What did you prepare?” Mr. Labovitz asked when I arrived.

It didn’t matter. I knew I wasn’t born to be a musician and Mr. Labovitz knew it too. But my mother insisted that I learn piano, he had to make a living and, at least, I liked music.

When I was seven, Franci bought an old upright and set aside half an hour a day to cajole me into practicing. She bought the appropriate books; she applied herself to my instruction with the concentration she applied to making clothes. But even if she hadn’t been tense from a day of managing customers and employees in her salon, my mother had no idea of how to teach. We would argue about which Easy Duet to play, I would complain that my part was too hard or boring, that I was tired or that she was playing too fast. In the end, I would flounce off and leave my mother on the piano bench alone, improvising jazz standards from the 1930s.

One day, I said if she didn’t find a real teacher, I would never touch a piano again, and she found Mr. Labovitz. She gave up the fantasy of my becoming a famous pianist but not her desire that I learn the repertoire she had learned as a girl: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and Chopin. They were, to her, my inheritance: part of the cultural capital of every well-brought-up European girl since the invention of its middle class.

Every six months, Mr. Labovitz held a recital in which his students performed for one another. He expected us to dress for the occasion and I wore an outfit from my mother’s salon. She made elegant, well-constructed clothes that a woman had to fit into rather than the other way around and I felt taller and more awkward than usual. I knew none of the other piano students and was relieved when Mr. Labovitz stood between the two grand pianos and asked everyone to find a seat.

“Hi Robbie,” he waved to a boy who came in just before the first student began to play. “Have a seat.”

The recital proceeded uneventfully. When it was my turn I went to the piano and when I finished, there was the requisite applause. I had made no major mistakes. But I was aware that every time I learned a piece of music, Mr. Labovitz had to show me how to play it, as though he were translating from a foreign language. Only rarely could I play what the composer intended the way that I could read a book and know what the author meant. After I returned to my seat, he said, “Robbie?”

The boy who came in late sat down at the piano. He rolled up the sleeves of his white shirt to the elbows. I noticed that his pants were rumpled, his hair uncombed. He leaned over the keyboard and seemed to be waiting for something. Then he dove into the music. The piano I had played sounded like a different instrument. It was evident that piano lessons were something that he loved. I was sure Mr. Labovitz never had to exhort him, as he did me, to “play with conviction!”

My mother worshipped men who played the piano. My father fell asleep at concerts, so from the time I was four or five, I was her date. We climbed the stairs together to the top rung of Carnegie Hall. My mother always bought tickets on the keyboard side so that through her opera glasses we could watch the pianist’s hands — as though by watching, you might learn to make magic.

For Franci, a concert hall was asylum, spa, and spiritual retreat in one. Taking me with her was a re-enactment of a ritual she had performed with her mother, before she lost her. For me, a concert hall was the rare place where I had my mother at least partly to myself.

She sat rapt at the edge of her seat, opera glasses to her face, while I zoned in and out of the music. When it was lively, I paid attention. When it was slow, I turned my mind to the pastry tray in the downstairs café. At intermission, before we left our seats, my mother opened her purse and took out her silver lipstick holder. She swiveled the red stick out of its container, and painted her lips bright red. Then we went downstairs to the café. While my mother and her friends smoked, I would gobble down an éclair or napoleon.

That Sunday afternoon when Robbie played, I paid attention to the music. He made the notes sound like words and, although I could not have said what those words actually meant, they spoke to me. It was over before I was ready. People stood up. Mrs. Labovitz asked me to help her in the kitchen. When I came back out, Robbie was gone.

For 30 years, even when we lived on different continents, Robbie and I kept in touch. He read what I published; I listened to what he composed and, later, to what he said on the radio. Every now and then, Robbie would propose that we collaborate on a project but I always found reasons to refuse. We weren’t a good fit. I liked clear objectives and deadlines; he liked chasing amorphous subjects. Most important, I thought I’d wind up as scribe to the genius.

But when I received my invitation to speak in California in the fall of 1999, I thought we might work together on a book. I had been thinking about first love, my atypical adolescence and how the massive trauma of the Holocaust had affected survivors and their children in the intimate realms of sex and friendship — a theme that I had not been able to delve into in my first book. But, almost as soon as I began thinking about myself as a teenage girl, I ran into gaps and great patches of murk.

Robbie, I reflected, was a reliable source. He had come to our home for dinner every week after we first met, was fascinated by my parents, and continued to visit throughout my adolescence. He had known my two younger brothers and most of my friends. He could validate what I remembered, and remember what I’d forgotten. He could serve as my archive, mirror and muse.

I questioned those words as soon as I thought them. Why would I need an archive to write a memoir? Wasn’t my own memory sufficient? And what made me think that Robbie would help? We hadn’t seen one another in a dozen years.

Robbie sounded unsurprised to hear from me, as though we were picking up a conversation interrupted a few days instead of a few years before.

When I told him I had been invited to speak at a college near his home, he said, “Come.” When I asked if he’d be interested in helping me research a book, he said, “Sure.”

I was relieved, then alarmed. Why was he agreeing so quickly? Boredom? Middle-age, with its autumnal mix of panic and regret? Was he also feeling a need to reconnect with his early life?

I knew better than to ask. Robbie often responded to questions as though they were provocations. Unlike my marriage to Patrick — late, stable, a broad band of shared experience — my relationship with Robbie was like a narrow radio frequency, subject to static and frequent loss of signal. It was something of a mystery why our connection had lasted as long as it had.

____________________________________________________________________

HELEN EPSTEIN (helenepstein.com), born in Prague in 1947, is the author of Children of the Holocaust and Where She Came From: A Daughter’s Search for Her Mother’s History. The former was the first book to examine the inter-generational transmission of trauma. The second was the first post-Communist reconstruction of Czech Jewish family history. The last book in the trilogy, The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma, is set in the postwar Czech community of New York City and addresses the long-term fall-out of sexual assault. Helen is the editor of Archivist on a Bicycle, a book about the late Jiri Fiedler and translator to English of Heda Kovály’s classic memoir Under a Cruel Star and Vlasta Schönová’s Acting in Terezin. She has also written about her father, the Czech Olympic water polo player Kurt Epstein, in the book A Jewish Athlete.