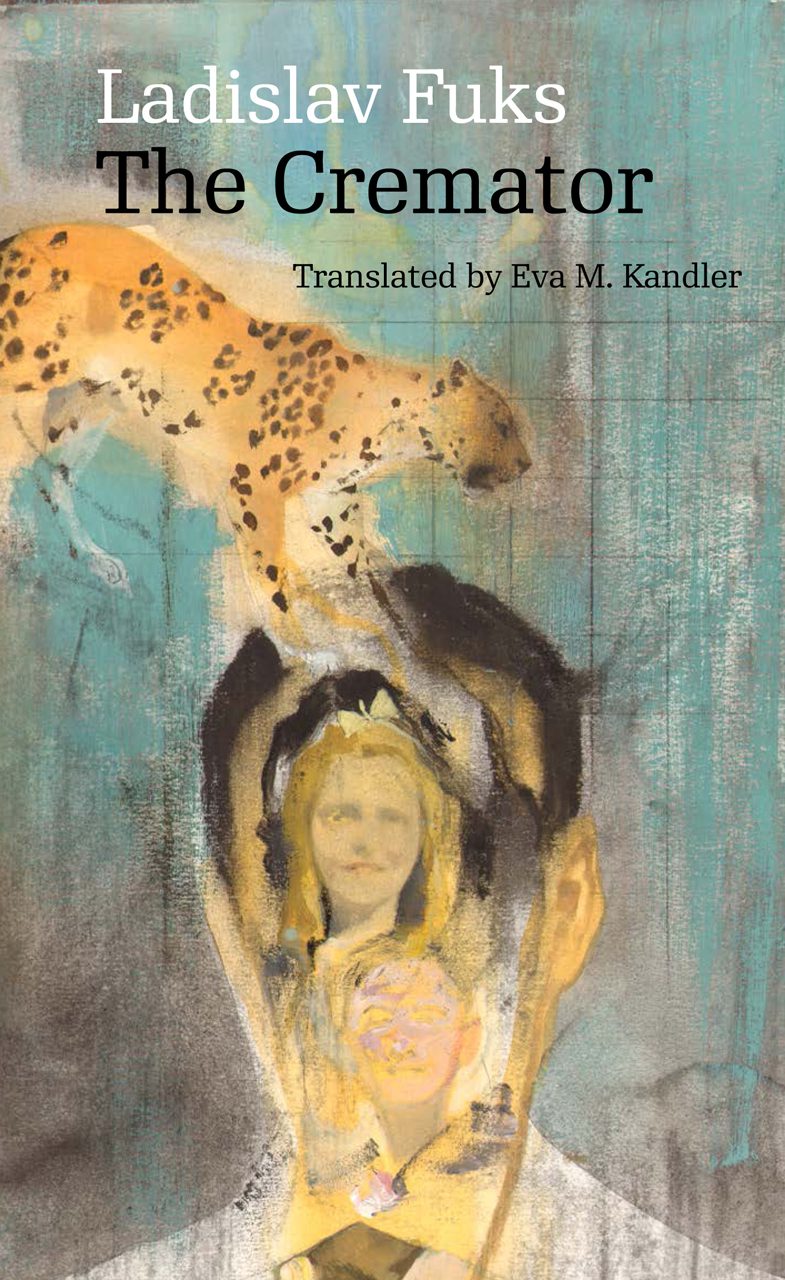

THE CREMATOR

(an excerpt)

The Cremator

A novel by Ladislav Fuks

Translated from the Czech by Eva M. Kandler

Published by Karolinum Press

The German Casino in Růžová Street, to which Mr. Kopfrkingl had dragged himself with his leg behind him and his body bent forward, had a white marble-covered entrance with three steps. ‘I love white marble-covered entrances with three steps,’ thought Mr. Kopfrkingl and slowly crossed the street to the pavement opposite. ‘They look like the entrance to some rich man’s villa. They could even be the entrance to some grand ceremonial hall. Willi’s inside,’ he thought. ‘Willi’s in there. I’ve never been inside, but I know it from his description. The carpets, mirrors, pictures . . . lavatories, bathrooms . . . first-class Prague German society, deputies, factory-owners, professors from the German University, not all of them of course . . . Mr. Boehrmann, who frequently goes to Berlin to consult with ministers, and first-class waitresses, barmaids and hostesses . . .’ Mr. Kopfrkingl reached the pavement opposite and involuntarily leaned against the wall of a building . . . Then he peered through his specs, shifted his leg slightly and bent his body so that Willi would find him in the correct posture when he came out of that white entrance with the three steps. As he stood in this manner against the wall of the building opposite and gazed at the white entrance, several people passed by without him noticing them at all. Except for one woman. She was slim and had biggish breasts. She was a complete stranger, he had never seen her before in his life. She dived into her handbag, and before Mr. Kopfrkingl could recover himself, he found a twenty-heller coin in his hand. He did not even realize that a split second before he had extended his hand with the palm turned upwards as he had done when he came out of the bathroom at home. His heart nearly stopped at this gift. ‘What a beautiful, good woman,’ he thought when he roused himself from his astonishment. ‘What proof that my disguise is perfect . . .’ At that very moment he saw his friend Willi walking energetically towards him from the Casino’s entrance.

‘Fantastic,’ Willi laughed, glancing after the woman, who was already far away. ‘Fantastisch, tadellos. Why, you’re completely changed. You’re acting it just like Chaplin. Come, let’s walk together a little bit,’ he gave a laugh, ‘nebeneinander . . .’

With his leg behind him and his body bent forward, Mr. Kopfrkingl walks slowly beside Willi and says with a glance at Willi’s elegant coat:

‘Won’t it attract attention – you walking with me?’

‘Why?’ says Willi. ‘Why shouldn’t a citizen of this republic walk with a beggar for a little bit? After all, this is a free, democratic country, isn’t it? Ausgezeichnet,’ he laughed with a glance at the feet, ‘du schleichst wie ein echter Bettler.’ Then Willi put his hands into the pockets of his elegant coat, lowered his head and said quietly:

‘You want to live up to your honour. You were born for big tasks,’ he smiled at the bluish face, shocks of hair and stubble beside him. ‘You’re getting along fine. You’re doing it brilliantly. You’re no weakling, you’re a one hundred-percent man, with a pure German soul. Just crawl along the streets for a while to reinforce your inner resolve, and then off to Maislova Street. If you shuffle along there before six, it’ll be the right time. Hang about the entrance, stick your hand out too. Gape at the plate by the gate. I told you, there’s a kind of little glass plate hanging by the entrance, you can read it, there’s a street lamp nearby . . . And then . . . try to catch . . . a few words. Einige Worte au angen. A few words, the kind people usually say when going inside. Nämlich, ‘Willi gave a laugh, ‘what Jews say when they enter the Jewish Town Hall on 6 March 1939, on Chevra sude, which is a festival. . . I’ll ask tomorrow.’ Then he said:

‘You know that they’re a wretched people who don’t understand anything. They’re so ancient, they’re senile . . . But you can help them,’ he said, ‘help them when we find out what they’re talking about, what their views are. Besides, this is nothing but a sort of little test for you, a training of sorts, as I told you at your place. Considering that you’ve been a member of the SdP since last month it’s necessary to undergo a little such training. The whole German nation has undergone training, much more difficult training, in uniforms, in the field, in sacrifices . . . the young people in the Hitler Youth in boxing. What’s all this crawling . . .?’ Willi jerked his head at his friend Kopfrkingl creeping along beside him. ‘Why, it’s just plain tomfoolery compared to that. Well, and you’ll also have to come to the Casino soon . . .’

Mr. Kopfrkingl smiled kindly, if it is at all possible to smile kindly in such a miserable beggar’s disguise, and said:

‘Beautiful carpets, pictures, bathrooms, you say . . . beautiful women?’

‘Beautiful women,’ Willi gave a laugh, ‘fantastic! You won’t find more magnificent, affectionate women anywhere in Prague, und doch die Eleganz! Look here, those Petites of yours from the Malvaz pub, those Liškas, Strunnýs, Čárskýs of yours, or whatever you call them . . . you’ve got to put a stop to that. You won’t need it. Does the meaning of your life consist of regulating the flow of coffins into furnaces and measuring temperatures for ever?’ Then he said:

‘You were born for big tasks, and so you’ll have to keep company with suitable people. Go to Maislova Street, to the Town Hall, to those erring ones, strain your ears. Today you shuffle there as a beggar, but one day you may go there in a Mercedes. In a beautiful, green military car . . . Well, go now, I’ll ask tomorrow. Geh . . .’

Willi Reinke left and Mr. Kopfrkingl said to himself:

‘He didn’t even give me the twenty-heller coin he was to pretend to give me. It wasn’t necessary. This amazing business makes me feel almost feverish. It’s more amazing than the silver casket. It’s just as interesting and strange, this change of mine, this transformation, as the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation in my book about Tibet, although it’s got nothing to do with it at all. Why, mine is just an ordinary kind of disguise, nothing more. If Mr. Fenek should see me now, poor thing. Or poor Mr. Dvořák,’ he recalled again, ‘but that doesn’t matter. My forehead is as cool as metal, my hand is firm and my heart’s beating as if it was made of Germanic steel. That’s the test!’ And steely calm and in disguise, he mingled with the poor unfortunate people in the street . . .

____________________________________________________________________

LADISLAV FUKS (1923–94) was a Czech writer of primarily psychological fiction. His novels include Mr. Theodore Mundstock.

The Cremator is being republished in December 2016.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

EVA M. KANDLER is a translator of Czech origin who has lived in the United Kingdom since the 1960s.