SECOND FISH FROM THE RIGHT

I wanted to show the photograph to my father

because I thought it would give us a reason to talk again:

an old man selling goldfish in Beirut, eight flat eyes stamped

into four orange orbs, each hung like holiday ornaments

on the branches of a black-dead tree, a photo taken

before one war, or just after another. I thought we could

talk about politics or post-war economies. But I forget:

—it doesn’t work like that when he’s angry.

In the living room, his eyes glaze over and follow

the dark shapes on the television, closing himself off

until someone does something he wants.

It’s a documentary— a man explains how to

train an orca whale. If the whale does what you want,

you reward it with food. If the whale doesn’t do what you want,

you do nothing, you hold still. This is positive reinforcement

and neutral reinforcement. The man explains an orca

has never been known to eat a human in the wild.

In the documentary, a woman says if you spent

twenty-five years in a bathtub, you would be a little psychotic, too,

as the camera zooms out to show a whale dragging

a woman to the bottom of the tank and holding her there—

through the glass, her body like a ragdoll in his mouth.

The camera fades to blackout, my father’s face glowing

in the screen’s afterimages, his hand finally

shoving away the photo that I’ve given him.

Nothing is forgiven. He’s still angry. Now,

he’ll punish the whole house with silence.

Upstairs, my sister guts her closet, the ceiling translating

the clack and scrape of hangers and shoes thrown into

the center of her room, thrown into walls and doors.

Down the hall, my mother draws a bath and sets her wine glass

on the lip of the tub to test the water with her hands.

She’s drinking again, my sister said to me, she has new medication,

I don’t want to be the one to drag her body out of the tub one day.

In the documentary: autopsy photos show a crushed torso,

severed limbs, a mouth bruised into an iris.

Later, my father refuses to eat dinner and goes to bed

alone. Later still, my mother leaves a snow globe on the piano,

her way of saying sorry, things have been hard lately, he didn’t mean it

when he shook you by the shoulders and called you a stupid bitch.

It’s December, and if I bought my father a goldfish,

he wouldn’t understand what I was trying to say: I understand,

it’s not hard to die as something that lived to eat for fear of being eaten.

He sets his jaw and turns in his sleep. Don’t pity anything,

he’d say. Don’t pity anything that only understands glass.

_______________________________________________________________________

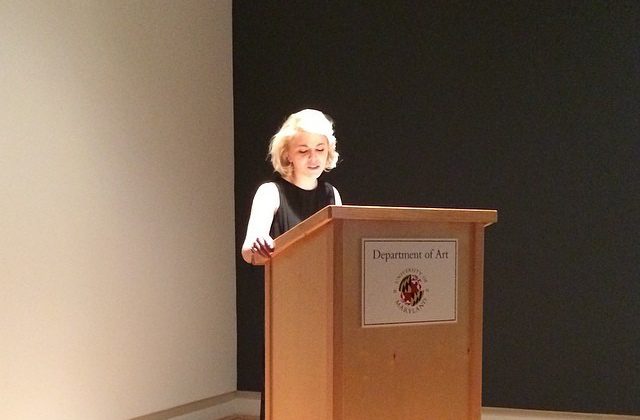

M.K. FOSTER‘s poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Gulf Coast; The Account: A Journal of Poetry, Prose, and Thought; Sixth Finch, District Lit; The Adroit Journal; Nashville Review; Cider Press Review; Word Riot; H.O.W. Journal; The Baltimore Review; Ninth Letter, and elsewhere. In 2013, her work was selected by Stanley Plumly for the Gulf Coast Poetry Prize, and in 2014, Sally Keith selected her poems for an Academy of American Poets Prize. She is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in English Literature through the Hudson Strode Program in Renaissance Studies at the University of Alabama, where her interests include trauma, performance theory, and the body.

_______________________________________________________________________

Read more work by MK Foster:

Poem in Cider Press Review

Poem in Gulf Coast

Poem in The Account

Poem in Sixth Finch

Poem in Ninth Letter

Poem in Radar Poetry