Editor’s Note: This is a condensation of sections from James Walling’s upcoming biography of the suspense novelist John D. MacDonald, to be published by Schaffner Press.

“I automatically buy every John D. MacDonald as it comes out, and not even MacDonald’s invention of a serial character, with all the dangers which I personally know so well, will deter me from continuing to do so.” –Ian Fleming

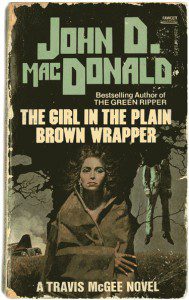

By 1962, the novelist John D. MacDonald relented to pressure from his editors and began preparations for the creation of a lasting serial character. The result would be the “salvage consultant” and reluctant rescuer of lost causes, Travis McGee. He would rival the great serial characters of the day (Archer, Bond, Wolf, et al.), with many titles in the series selling more than a million copies in early editions.

Having achieved notoriety and success in the pulp magazines, and with more than 40 novels already in print, MacDonald introduced a character that would eventually dwarf his previous publishing efforts. He would become the bedrock of MacDonald’s career, establishing a vast, devoted audience, and an almost sublime literary legacy. As the epitome of this legacy, the McGee series transcends genre fiction, and is rich with piercing psychological insight, social commentary, and clean, compelling prose that lapses into poetry.

I wasn’t immediately impressed. The lurid covers and pulp marketing aesthetic put me on notice—these are not intellectual novels. Or so it initially seemed to me when handed a copy of Cinnamon Skin (1982) by an influential mentor. The mentor had steered me toward Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, had introduced me to the work of Jiddu Krishnamurti and the novels of John Fowles, and he insisted quite sternly that I give MacDonald a try.

I wasn’t immediately impressed. The lurid covers and pulp marketing aesthetic put me on notice—these are not intellectual novels. Or so it initially seemed to me when handed a copy of Cinnamon Skin (1982) by an influential mentor. The mentor had steered me toward Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, had introduced me to the work of Jiddu Krishnamurti and the novels of John Fowles, and he insisted quite sternly that I give MacDonald a try.

The memory is crystalline. Holding that paperback with the fetching dead woman sprawled across the cover in my hands, flipping skeptically from page to page thinking, nope, nope, pulp, sexist, boring… beautiful, wait, full stop. This is some of the best writing I’ve ever read. It was stunning. It’s an experience many MacDonald fans will recognize and relate to.

Though destined to span 21 novels—each employing a different color or shade in the title—the McGee series was by no means a sure success at the outset. MacDonald would shelve two aborted attempts at The Deep Blue Goodbye (1964), before settling on a character that suited him.

Originally christened “Dallas” McGee, the character’s name was changed after John F. Kennedy was shot in Texas. The name “Travis” is purported to have occurred to MacDonald after he perused a list of Air Force bases at the suggestion of the writer MacKinlay Kantor. Even then, he would insist that his publishers hold onto the book until he could complete two more titles, A Nightmare in Pink, and A Purple Place for Dying, which were eventually published in three successive months in 1964 to positive commercial and even limited critical response.

The notion of MacDonald creating a serial character was suggested by one of his editors, Ralph Daigh, as early as 1952, but MacDonald resisted the idea for fear that he would be unable to pursue other subject matter if he took on a series so early in his career. The notion took hold nonetheless. After following his friend and editor Knox Burger from Fawcett Gold Medal to Dell in 1958, MacDonald began to seriously consider tackling a series.

The character had its genesis in MacDonald’s earlier protagonists, and was informed by his personal history. In his introduction to The Good Old Stuff (Harper & Row, 1982), Francis M. Nevins, Jr. says of MacDonald, “He was writing about disturbed war veterans […] including one or two recognizable prototypes of that perpetually disappointed beach bum and contemporary knight, Travis McGee.”

In correspondence with this author, Nevins Jr. shared his conviction that the early pulp character of MacDonald’s with the strongest resemblance to McGee was the protagonist Max Raffidy in A Corpse-Maker Goes Courting (1949).

Like MacDonald, who served with the OSS in the India-China-Burma Theater of Operations in WWII, McGee is a veteran of war. He is also a cynic about consumer culture, an early conservationist, and a lover of books, boats, liquor, food, good company, and sporadic attempts at the good life, all of which are perpetually sidelined by attacks of conscience.

MacDonald shaded his hero’s mythic manliness somewhat by bestowing upon him a seemingly hedonistic, counterculture lifestyle, with McGee inhabiting his mythical houseboat at slip F-18, Bahia Mar, a few slips away from the Alabama Tiger’s perpetual floating house party. The balancing force in this amusing milieu is McGee’s chivalric sense of self, and his general disinterest in joining any parties for long, even agreeable ones.

More than anything else, however, it is the combination of McGee’s keen sympathy with all but the darkest aspects of human nature and MacDonald’s remarkable prose that lifts the character out of the ranks of the Sam Spades and Mike Hammers. With McGee, we witness MacDonald at the height of his powers. In this one series, he was able finally to fuse a synthesis out of the conflicting styles and narrative oddities in his considerable repertoire.

Having come to prominence through the pulps in the same manner as Hammett and Chandler, MacDonald did his business in a medium consisting of strict narrative rules and character types. By the time he created McGee, however, his prose was consistently formed in the clean, muscular, and often poetic tradition of American writers like William Dean Howells, Faulkner, and even Hemingway. See, for example, the following short passage from The Deep Blue Goodbye, replete with MacDonald’s signature marriage of restraint and lyricism:

Having come to prominence through the pulps in the same manner as Hammett and Chandler, MacDonald did his business in a medium consisting of strict narrative rules and character types. By the time he created McGee, however, his prose was consistently formed in the clean, muscular, and often poetic tradition of American writers like William Dean Howells, Faulkner, and even Hemingway. See, for example, the following short passage from The Deep Blue Goodbye, replete with MacDonald’s signature marriage of restraint and lyricism:

I listened for the roar of applause, fanfare of trumpets, for the speech and the medal. I heard the lisping flap of water against the hull, the soft mutter of the traffic on the smooth asphalt that divides the big marina from the public beach, bits of music blending into nonsense, boat laughter, the slurred harmony of alcohol, and a mosquito song vectoring in on my neck.

MacDonald’s writing is clear and powerfully interesting. It is difficult indeed to find much in the way of unnecessary or uncommunicative writing anywhere in the series. MacDonald’s maxim “anything unnecessary is bad art” might have been Hemingway’s personal manifesto. The maxim in question is a reiteration of MacDonald’s feelings found in the highly-recommended A Friendship: The Letters of Dan Rowan and John D. MacDonald, 1967-1974 (1986), a useful source for readers interested in MacDonald’s personal life.

Allusions to Great Literature aside, perhaps the most striking feature of the McGee series is its accessibility. Fans of the series will tell you that the passive reader is just as likely to find the books entertaining as the lover of literature, regardless of whether either fully appreciates the deftness and richness of the prose.

The Scarlet Ruse (1972) provides another example of that unique combination of gritty descriptive detail and confessional, almost apologetic self-revelation that typifies MacDonald’s narrative style in the series. In it, he describes McGee attending the performance of a Spanish dance troupe:

I could see soiled places on the costumes. I could smell the fresh sweat of effort mingled with the stale sweat of prior engagements, trapped in gaudy fabric, released by heat. I could hear the dancing girls grunt and pant. I could see dirty knuckles, grubby ankles, and soiled throats. […] Ten rows back the illusion must have been perfect. But I was too damned close to the machinery, and it killed the magic.

In The Quick Red Fox (1964), MacDonald demonstrates the kind of social commentary and efficiency of line that separated him from the main body of genre hacks and allowed him to voice acerbic social criticism:

Their schools are group-adjustment centers, fashioned to same the rebellious. Their churches are weekly votes of confidence in God. […] The goods they buy grow increasingly shoddy each year, though brighter in color. […] You see, dear, there is no one left to ask them a single troublesome question. Such as: Where have you been and where are you going and is it worth it.

In the series, at least, there is someone left to ask the question—McGee. The character’s prerogative is paramount, but none of the books are mere mouthpieces for MacDonald’s musings, or a vent for his personal frustrations. The author juxtaposes commentary with compelling plot-lines, visceral action, and passages of unadulterated, naturalistically descriptive prose, the likes of which are rarely found in the works of mystery novelists from the period.

In the series, at least, there is someone left to ask the question—McGee. The character’s prerogative is paramount, but none of the books are mere mouthpieces for MacDonald’s musings, or a vent for his personal frustrations. The author juxtaposes commentary with compelling plot-lines, visceral action, and passages of unadulterated, naturalistically descriptive prose, the likes of which are rarely found in the works of mystery novelists from the period.

Though known primarily for his detective stories, MacDonald wrote substantial science fiction and nonfiction works that are well worth pursuing at length. He was, and remains, an unsung generalist.

MacDonald’s background in a variety of literary styles is especially evident with McGee. In writing the character, he faced one particular technical difficulty that he had largely been able to gloss over in his standalone books. He explained the problem in “How A Character Becomes Believable,” published in Writer’s Digest in 1976. In it, he wrote, “The first-person treatment is seriously self-limiting. The ‘I’ must say all that is in his mind and heart. There is no good way to dimensionalize that ‘I.’ All psychic reactions are flattened out.”

MacDonald was nine books into the series before he found a satisfactory solution to the “self-limiting” aspect of his decision to write McGee as a first-person narrative. The introduction of the character Meyer in Pale Gray for Guilt (1968) was in many ways designed to solve this problem. With Meyer, MacDonald’s troubles became more manageable and the series deepens considerably.

During an interview for Criminal Intent, MacDonald commented: “I just got bloody tired of having McGee go through those interior monologues to explain to the reader what was going on. I finally realized I was going to have to have somebody he could bounce conversations off.”

Meyer—stout, hairy-chested, lovable Meyer—provides a dependable sounding board for McGee, and adds greater depth of perception in the form of side comments, sage advice, bad jokes, stern lectures, and warnings. According to McGee (from 1973’s The Scarlet Ruse): “[Meyer] can put a fly into any kind of ointment, a mouse in every birthday cake, a cloud over every picnic. Not out of spite. Not out of contrition or messianic zeal. But out of a happy, single-minded pursuit of truth. He is not to blame that the truth seems to have the smell of decay and an acrid taste these days.”

Meyer is McGee’s Carta Blanca-swilling Sancho Panza. By comparison, MacDonald granted Meyer a significantly higher IQ than most fictional sidekicks. No fumblingly helpful Doctor Watson, and far less clownish than Panza, Meyer makes his living as an economist, formulating theories such as this one from The Green Ripper (1980): “I remembered one of Meyer’s concepts about cultural resiliency. In the third world, the village of one thousand can provide itself with what it needs for survival. Smash the cities and half the villages, and the other half keep going. In our world, the village of one thousand has to import water, fuel, food, clothing, medicine, electric power, and entertainment. Smash the cities and all the villages die.”

Curiously, Meyer’s quirks and idiosyncrasies appear to have born a stronger resemblance to MacDonald the man than those of his protagonist. The author took a multiphasic personality inventory test three separate times at the University of Alabama; once as McGee, once as Meyer, and once as himself. The results strongly suggest that MacDonald’s thinking was more often in line with Meyer than he was with McGee. The psychology of it is pretty straightforward, as is the inescapable conclusion: Meyer observes and comments on both McGee and the world in much the same way that MacDonald did himself. They are, at least in this significant sense, one and the same.

In his personal life, MacDonald sometimes employed Meyer as a mouthpiece for what he referred to as his “pretentious elliptical sermons.” In letter to Dan Rowan, he hid behind Meyer in order to lecture his friend on the psychology of addiction, before signing off, “I told Meyer that by God he certainly wasn’t much help, and all he said was, ‘We are what we are and we do what we do, and the thing is to get all the way around the track without falling too many times and without running too many people into the rail.’ He yawned, scratched his hairy chest and went back to his damned girl-watching. I think he is an idiot, talking all that guilt and expiation stuff. Next thing you know he will be popping off about love, truth and beauty.”

The Meyer character is so thoroughly imbued with MacDonald’s personality that it can be easy fails to breeze right past his functionality as a literary device. “Get all the way around the track without falling.” That’s another maxim. His role is just the sort of innovation that prompted MacDonald to proclaim in Writer’s Digest, “As the characters in mystery fiction become ever more fully realized, the dividing line between the mystery and the straight novel becomes constantly more vague.”

Before we get going about the inadequacy of genre classification in the branding of MacDonald’s work, it must be admitted that the series is unabashedly genre-specific in one undeniable respect. The subjects of sex and sexism come part and parcel with the lurid covers adorning many editions of the books. McGee falls into females often, and often as not for therapeutic reasons, sympathy, physical satiation, egotism, and plain old boredom. And like Philip Marlowe, he turns down nearly as many interested ladies as he ends up going to bed with.

In the light of modern feminism (and common sense), there is a case to be made that MacDonald was both sexist and a chauvinist. There is no denying the evident condescension McGee sometimes offers his female cohorts in the guise of kindliness and attentiveness. And yet, perhaps McGee may be viewed more accurately, or at least more sympathetically, through the lens of postfeminist thought offered in the work of Camille Paglia, among others. McGee’s lovers may have been routinely duped by other men, controlled by other men, wounded by other men, but they gave themselves willingly to McGee, and always for their own clearly apprehensible reasons, sensible or otherwise.

McDonald’s female characters developed demonstrably following his years in the pulps, and by the time he was worrying-out the goings-on aboard The Busted Flush, he had added considerable depth and dimensionality to the women who appeared in his fiction. It can be profitable to investigate and compare just how much “dimensionality” MacDonald’s male secondary characters possess in contrast to his women. In my reading, many of the female characters in the McGee books are actually a good deal more complex than their male counterparts.

In defense of our potentially sexist friend, one can offer the following passage from The Girl in the Plain Brown Wrapper (1968). It is hard to imagine lines like these coming from the mind of a true chauvinist:

In defense of our potentially sexist friend, one can offer the following passage from The Girl in the Plain Brown Wrapper (1968). It is hard to imagine lines like these coming from the mind of a true chauvinist:

So in the sensual-sexual-emotional areas each man and each woman has, maybe, a series of little flaws and foibles, hang-ups, neural and emotional memory pattern and superstition, and if there is no fit between their complex subjective patterns, then the only product you can expect is the little frictional explosion, but when there is the mysterious fit, then maybe there are bigger and better explosions down the in the ancient black meat of the hidden brain, down in the membraned secret rooms of the heart, so that what happens within the rocking clamp of the loins at that same time is only a grace note, and then it is the afterglow of affection and contentment that celebrates the far more significant climax in brain and heart.

On the subject of race, MacDonald was decidedly not good. He allied himself with the plights of minorities on a handful of occasions in his work (most notably in McGee), but always from a distance, and always speculatively, sympathetically even, but ultimately, it must be admitted, somewhat condescendingly. It’s my surmise that his condescension was more ingratiation than ignorance. His prerogative, that of an earnest onlooker rather than an active participant in the discussion of race in America. On that count, the jury has yet to even seriously enter into deliberations, let alone return a verdict.

Add to this mixture of authorial qualities the curative effects of self-awareness (he seemed to know that he didn’t understand much about the inner lives of minorities, and limiting his commentary accordingly), as well as the makings of an early conservationist, and a passionate social commentator on issues other than race, and one can overlook the near absence of racial politics in his work, or simply mark the topic a laudable one for further analysis. He penned as many novels as Balzac, after all. There is much else to discuss.

It wasn’t until MacDonald hit the meat of the books featuring his famous serial character that some serious critics finally began to praise his work without first qualifying him dismissively as, “genre writer,” “pulp writer,” or “mystery writer.” In reviewing The Dreadful Lemon Sky (1975) for The New York Times Book Review, Jim Harrison wrote, “MacDonald could never be confused with the escapism that dominates the suspense field. You would have to be batty or ignorant or a masochist to read a MacDonald novel for pure amusement […] MacDonald is a very good writer, not just a good ‘mystery writer.’”

In The New Yorker that same year, Naomi Bliven wrote, “There is […] the usual keen depiction of the moral grubbiness of contemporary American life, there is McGee’s oddly appealing and highly unfashionable integrity, and there is Mr. MacDonald’s total command of his craft.”

Of course, some critics continue to apply the stigma of genre to MacDonald’s work. Many academics and literary critics persist in dismissing MacDonald as the personification of the best that a bastard stepchild of serious literature can do. Note the distressing lack of attention paid to MacDonald in American universities—excepting a current vogue for courses devoted entirely to detective fiction.

Storyteller that he was, MacDonald can indeed be separated from the mainstream of American novelists today, many of whom have tended more frequently toward attempting either the humble task of reinventing the concept of narrative storytelling from scratch, or perfecting the manipulation of its perceived inert corpse. MacDonald’s business was different. He confided in the book critic Jonathan Yardley, “I do like the guys like John Cheever that have a sense of story, because, goddammit, you want to know what happens to somebody. You don’t want a lot of self-conscious little logjams thrown in your way.”

MacDonald worked within the strictures laid down by a combination of financial necessity, and the traditions of the narrative arc, as it had come to him from Aristotle to the Victorians, right up to his service in the war and the publishing of his first story, “Interlude in India,” inStory Magazine in 1946. The piece began as a letter written to his wife during wartime. It was both necessary (he was in a clandestine branch of service, and there were censors), and designed to capture the reader. It is for this writerly tendency that his work has been qualified, even by some savvy readers, as first-rate, second-rate stuff.

If ill treatment at the hands of the critical establishment ever got under MacDonald’s skin however, it wasn’t enough to alter his aesthetic sensibilities regarding his work. In a letter to Nevins Jr., he makes his tastes plain:

First, there has to be a strong sense of story. I want to be intrigued by wondering what is going to happen next. I want the people that I read about to be in difficulties—emotional, moral, spiritual, whatever, and I want to live with them while they’re finding their way out of these difficulties. Second, I want the writer to make me suspend my disbelief…. Next, I want him to have a bit of magic in his prose style, a bit of unobtrusive poetry. I want to have words and phrases really sing. And I like an attitude of wryness, realism, the sense of inevitability. I think that writing—good writing—should be like listening to music, where you identify the themes, you see what the composer is doing with those themes, and then, just when you think you have him properly identified, and his methods identified, then he will put in a little quirk, a little twist, that will be so unexpected that you have to read it with a sense of glee, a sense of joy, because of its aptness, even though it may be a very dire and bloody part of the book. So I want story, wit, music, wryness, color, and a sense of reality in what I read, and I try to get it in what I write.

The major themes at play in the McGee series are easily identifiable by the reader. Firstly, there’s heroism. Right from the start in The Deep Blue Goodbye, we stumble across Quixote, with his bent lance and busted steed, clearly evinced as McGee putts off in his ludicrously converted Rolls Royce pickup truck to come to the aid of Kathy Kerr, his backwoods damsel in distress.

Attempting, as McGee does, to indulge in chunks of retirement while young enough to properly enjoy them, McGee often agrees to assist wounded parties recover lost items or mete out vigilante justice for no other reason than his innate inability to ignore the pleas of the innocent. But this trait isn’t evinced without at least a hint of complicated feelings on the theme from McGee in The Empty Copper Sea (1978): “I had a sudden wrenching urge to shed my own identity and be somebody else. Somehow I had managed to lock myself into this unlikely and unsatisfying self, this Travis McGee, shabby knight errant, fighting for small, lost, unimportant causes.”

Not too surprisingly (spoiler), he never does succeed in shedding his identity. The second-to-last installment of the series, Cinnamon Skin, finds McGee in a seemingly hopeless attempt to track down a serial killer in a sprawling epic, by the standards of the series, that takes him clear across the country and down into the jungles of Mexico in pursuit of his villain. Even at this late stage, McGee is driven by his desire to set things right, regardless of the risks.

In the midst of slaying metaphorical dragons, locating needles in daunting stacks of hay, and defending the honor of the meek and the mild, McGee still manages to find time for love, and the alternately hopeful and tragic aspects of romantic love are important thematically. Despite the staggering number of casual affairs McGee partakes in (best estimate: 50), a handful of serious love affairs gain in significance as the series progresses.

There is Gretel Howard, whose murder drives McGee into a dark obsession with revenge and retribution in The Green Ripper, the book that won MacDonald an American Book Award in 1980. And there is Annie Renzetti, who steals McGee’s heart in two books, Freefall in Crimson (1981) and Cinnamon Skin, exhibiting nicely the vulnerability and fear of mediocrity at the core of McGee’s bachelor lifestyle. Quoth McGee in The Empty Copper Sea:

I am apart. Always I have seen around me all the games and parades of life and have always envied the players and the marchers. I watch the cards they play and feel in my belly the hollowness as the big drums go by, and I smile and shrug and say, Who needs games? Who wants parades?

McGee cannot help longing for stability and emotional security, even if it remains largely unobtainable for him. Formula dictated that McGee remain alone and “apart.” And one of MacDonald’s favored methods for extricating McGee’s partners from his life was to kill them off.

Unlike many protagonists in the annals of suspense fiction, McGee suffers the loss of his various lovers tremendously. Even more than the military horrors in McGee’s past, the deaths of his inamoratas contribute to the gradual hardening of McGee’s character, and the increasing note of melancholy in the stories.

Themes of love and loss recur and intensify as McGee advances in age. Although MacDonald didn’t intend for The Lonely Silver Rain to be the final installment in the series, a rare subplot (spoiler) lends additional poignancy when McGee discovers that he has a daughter, the lovechild of an ancient affair with Puss Killian, his lover in Pale Gray for Guilt. The emergence of a daughter at this late stage, even a grown daughter, provides McGee—and the series too—with a symbol of absolution and an undeniable sense of finality. How would McGee continue on in the usual solitary way once he knows that there is at least one person in the world for whom he is truly, ultimately, and permanently responsible? He wouldn’t is all, and he didn’t.

Apart from chivalry, love, loss, retribution and redemption, one thematic element in the series stands out as well ahead of its time. McGee repeatedly demonstrates a deep abhorrence of the degradation of the natural environment, both in America in general, and more specifically in MacDonald’s beloved Florida. To say that it was unusual to find an environmentally sensitive protagonist in a mystery novel as early as 1962 is something of an understatement. In his fiction and his life, MacDonald proved to be overflowing with vitriol on the subject of the environment (from Cinnamon Skin): “We’re getting a thousand new residents a day … We get thirty eight million tourists a year … And the rivers and swamps are dying, the birds are dying, the fish are dying. They’re paving the whole state … Everything is going to stop working all at once. Then watch the exodus.”

Such sentiments became typical of McGee. Hardly a book in the series is without similar observations. It was certainly old hat for MacDonald, whose scathing opinion pieces appeared regularly in the Florida press, often published under a pseudonym. He also fought several quixotic battles of his own with greedy, shortsighted developers near his home on Siesta Key.

Many of McGee’s rants could have been selected at random from MacDonald’s personal correspondence, such as the following passage, also from Cinnamon Skin:

Florida was becoming second rate, flashy and cheap, tacky and noisy. The water supply was failing. The developers were moving in on the marshlands and estuaries, pleading new economic growth. The commercial fishermen were an endangered species. Miami was the world’s murder capital … Wary folks stayed off the unlighted beaches and dimly lighted streets at night, fearing the minority knife, the ethnic club, the bullet from the stolen gun.

Controversial language won him some enemies, but many more fans and admirers. It is now common to come across liberal sentiments in genre fiction, and this is due in no small part to MacDonald’s unflagging stubbornness in the face of the destruction of Florida’s environment and culture. The novelist Carl Hiaasen, who claims MacDonald as a significant influence, summed up the feelings of a great many Floridians on a blurb for a reissue of McGee, writing, “Most readers loved MacDonald’s work because he told a rip-roaring yarn. I loved it because he was the first modern writer to nail Florida dead-center, to capture all its languid sleaze, racy sense of promise, and breath-grabbing beauty.”

Lauded by the Miami Herald as “the pre-eminent ‘Florida novelist,’” MacDonald still aspired to broader appeal and influence. Hollywood tempted his hunger to reach the broadest audience possible with an assortment of ever-changing and ultimately disappointing projects.

After the qualified cinematic success of Cape Fear in 1960 (the terrific adaptation of MacDonald’s The Executioners (1957) by director J. Lee Thompson), each successive instance of MacDonald on the screen has been intermittently more insignificant. One exception may be the excellent remake of the aforementioned classic (1991, Dir. Martin Scorsese). In any case, it certainly holds true with McGee. The most widely viewed product of the endless negotiations and potential projects that MacDonald considered for McGee is 1970’s film adaptation of Darker Than Amber (1966).

According to critic and McGee aficionado Mike White: “Despite the ad copy that declared, ‘Rod Taylor IS Travis McGee’ I don’t feel that Mr. Taylor really captured the knight errant. He had the tan, yes, but that was about it.”

The other remnants of leftover attempts at bringing McGee to the screen belong to the scrapheap of media speculation, with only 1983’s television movie adaptation of The Empty Copper Sea, starring Sam Elliot, deserving of much more than passing comment.

The question of McGee’s ultimate cinematic fate remains open—particularly with recent adaptations being bandied about by the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio, Oliver Stone, and Christian Bale, among others, but the fact that he will live on in print is beyond doubt. He is waiting to be discovered by new readers, revisited by core fans, analyzed by critics, students and scholars, and imitated, if rarely duplicated, by writers scribbling in every conceivable genre.

It has been widely rumored that MacDonald had plans for a final “black” book, in which McGee would perish. MacDonald acknowledged the existence of some sort of treatment for the book, but made it clear that it was not his intention to publish it. He also claimed to have used the “black” concept to keep his publishers in check with the fear of killing off a cash cow.

He was specific about his plans for the end of the series, commenting during an interview with Peter J. Heck, “I’m gonna [end] with the twenty-second book. I got it blocked out enough to know that if the book goes alright, which I trust it will, he’s gonna pull up stakes with a bunch of about five or six other boats, good friends and whatnot.”

Of course we shall never have the final installment to cap the series off, and McGee remains the ripest fruit from an exceptionally abundant tree. MacDonald gave his best and most mature efforts to the series, and it is fitting that these are the books for which he will be best remembered. He effectively died writing, and writing well.

The successes of MacDonald’s substantial earlier works, particularly Slam The Big Door (1960), and The Drowner (1963), as well as his considerable contribution to the pulps, were remarkable within the context of the suspense field, but pale by comparison to McGee. One thing is clear—the sheer volume of MacDonald’s output in the years leading up to 1962 amounted to superb and unusual training for the daunting task of bringing an iconoclastic and deeply human character into the world of fiction.

The establishment of a serial character required MacDonald to work within the strictest confines of setting, characterization, and narrative that he would encounter professionally. The effects of such constraints were extremely positive, normalizing, and creatively liberating for MacDonald.

Great art has as much to do with limitation as it does with freedom. Jazz artists improvise within the strictures of keys and scales. Action painting takes place on a canvas. Many American novelists have a lot to learn from the writers in their midst who bind themselves to the traditional narrative arc and the conventions of genre. With the McGee series, MacDonald made as convincing an argument for this point of view as any American writer in the twentieth century.

When I first set myself to the task of writing about MacDonald, I did so with gusto, obtaining hard copies of everything he put into print, down to those odd bits of moneymaking that MacDonald himself hoped would disappear from the stacks.

Having read virtually all of it, and having handed copies off to writer friends in an attempt to solicit notes on themes, characters, structure, and so forth, I collected the books again, packed them all into a suitcase along with the most recent draft of a biography, and relocated to the Czech Republic via an Aer Lingus flight through Dublin. Somewhere en route, the suitcase was lost, its contents banished to a nether region of misbegotten personal effects.

–James Walling

_______________________________________________________________________

JAMES WALLING is a newspaper editor based in Montana. As a journalist and critic, his work has appeared in The Austin Chronicle, MauiTime, National Geographic Traveler, The Portland Mercury, The Prague Post, The Vancouver Voice, and Willamette Week, among others. His forthcoming biography of the American suspense novelist John D. MacDonald is being published by Schaffer Press.