THE DEATH OF A CZECH DOG

A few years ago the Roma settled in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. To fight for their recognition as a German minority group and to compensate for “that time then” they thought it best to wage war where they perished before, hence Bergen-Belsen, hence the hunger strikes in Dachau. Still, no matter how spectacular the protests not a single fucking bigshot paid any attention to them. In fact they protested for so long that they learned to live in this state of protest, and for a long time before the police finally decided to move them out, Bergen-Belsen was their home.

It’s 9 a.m. I’m sitting in bed, head slumped and eyes closed because the pigeons have been gabbling since dawn. Again. One “dove” in fact, the symbol of peace, love and the Holy Spirit, a soloist deadlier than a pack since a soloist irritates but a choir lulls to sleep. So again I sit up in bed, curse, then get up and stumble to the mailbox to find a lone advertisement for the supermarket’s 49th anniversary. I head to the supermarket to maybe get something. I don’t get anything, but on on my way out I walk past a grill and spot rotisserie chicken at special anniversary prices: half a chicken for two euros, with a bread roll. I buy one and sit on a bench in the sun, in nice weather, eating with my hands, just the way I like.

An old man walks by with an old dog. The dog limps and he limps too, and I worry about my chicken but he has one of his own and the dog doesn’t pay any attention to me.

The old man sits on the bench next to me, feeds his dog and the dog eats. I eat, too. The phone plays a tune in my pocket. I can’t pick up. My hands are greasy, since I’m eating with my hands. I eat, and the phone plays a tune like it was programmed to do, and though each time I mean to put it on vibrate, I get called so rarely that I always forget.

Bench, sun, chicken, and this jolly, idiotic tune. Two Polish women walk by:

“Look! See, even beggars have it good here. A bench, sunshine, chicken and music. A lifelong picnic!”

“How do you know he’s a beggar?”

“Isn’t it obvious? I’ll bet you!”

“But how would we find out?”

“I’ll give him some change.”

“Stop it. I think he’s a Gypsy.”

They walk on and walk past me. I finish eating and head home. At home I lie down, tired of this gabbling world. Not a successful first half of the day but not a bad one either. There were worse before or afternoons, and how many days toppled down the stairs entirely…

Should the second half bring nothing I won’t complain since I’ve had many successful evenings and nights and a person shouldn’t expect too much considering we’re all just lonely buoys afloat a sea of the everyday, right?

I doze off. Maybe something will wake me. If not, I won’t complain even if I want to since how can I when I’m asleep?

A dog on the phone barks and wakes me. The phone wakes me, and a dog barks on the other end. A dog is calling me? In a moment a man’s voice comes to the foreground, an indecipherable and soft kind of voice you could touch by putting a finger to the gums. The voice of the old man says – asks – if it was me who posted that ad for dog walking services.

“Yes,” I say, “it was me.”

“Well, it was me who called you earlier about this very matter, but no one picked up.”

“Someone called, but I was eating chicken with my hands because my supermarket is having an anniversary sale, you see . . . I couldn’t . . .”

“The supermarket? . . . I was there, got half a chicken for the dog and . . .”

“And your dog limps?”

“He limps and I limp. How do you . . . ?”

“And you fed him chicken by the bench?”

“On the bench! How would you . . . so, it’s you! You sat next to us, on that bench?”

“And that’s when you called me?”

“I did. And that . . . that little song?”

“My phone . . . I forgot to put it on vibrate because, you know, I get called so rarely . . .”

“What a small world this is! You on that bench, me on that bench . . .” And then he asks, “so . . . can you come over?”

I tell him I can and ask, “When?”

“Today. Now— if you can.”

I tell him I can and ask, “Where?”

“Well, that’s old age for you,” he says and asks if I have something to write with.

He gives me his address, name, and explains that he scribbled in his last name by the buzzer downstairs, “Illegibly, but you know, I write like I talk and I talk like this because I have no teeth left.”

I’ll go, I’ll take his dog out, why not. I had a dog once. I had her until she died. A boxer. Asta. When she got sick the vet said he’d come and put her to sleep. She lay on her side and watched me from the kitchen floor. I never gave her chicken because I was afraid the bones would hurt her. That day I bought her half a chicken from a rotisserie. She ate it lying on her side. The vet came and gave her sleeping pills. She threw up her last supper and died. I lived in an apartment complex next to the woods. I went to the woods, dug a hole, and to avoid making a scene, I waited until dark to bury her. Snow covered the ground. She was heavy. I put her on a sled and walked back and forth trying to remember the exact spot of the hole. It was dark, I was looking for the spot, and I couldn’t find it. It was hard to maneuver the sled around the trees. After a while I left her and walked around cussing until I found the hole by almost falling into it. When I walked back to get her, I walked and walked and I couldn’t find her—I thought I lost her. What is this? “Asta!” Her name slipped out – if this would’ve gone on a little longer I would have started whistling. Until finally, by almost walking into her, I found her and buried her, thinking, when you have a dog, you don’t have a hole and when you have a hole, you don’t have a dog and that’s just how it goes.

I ring the buzzer when I get there and walk up the stairs. There are so many shoes stacked by the doors that I think of Auschwitz. I introduce myself. The old man says he feels lousy, terrible in fact. The dog has to be taken out twice a day and he can’t manage anymore. He says he limps, the dog too, and sometimes the dog has to be carried down the stairs, up is just too hard, and there are so many shoes in the corridor that it’s hard to get through because the Turks, they live there, that’s why. Then he says I should feed him, feed the dog, I should put the food dish out and the dog will get used to me. Haf-haf barks the dog, that’s how a dog barks in Czech, in the village of Medlov-Králová. A pretty name, no? That’s where he got it. He was born in that village, and that’s why he got a dog from there, too, so the dog can go haf-haf in Czech and not some woof-woof. His daily dose of Czech, that dog is. I put the food dish out for the dog and the dog eats. When he finishes, the old man turns to me and tells me I can take the dog out to the park and when I come back we’ll talk business.

I joke and tell him that I’m sure we won’t have a problem that we can reach an agreement better than the one they came to for the Zaolzie region. Then he laughs and I laugh.

I climb down the stairs with the dog. Every step for him is a Velká Pardubická steeplechase. I take him into my arms, climb down slowly, and goddamn all those shoes. We walk down the street, I hold his leash and he trails behind me, slowly. Suddenly, out of nowhere, an ambulance appears and rushes by— it must have turned its siren on just before the intersection. It goes past us, I tug on the leash and nothing. Resistance. I turn around and the dog is lying on the ground, limp. I call him, tug on the leash, but the dog just lies there. A pregnant woman walks by bends over the dog, touches his neck and pronounces him dead. She can hardly get up with that belly. I help her get back on her feet and she says that the last thing she needs right now is for her water to break. I ask if I should call for an ambulance. She says no, it’s too early, and I should tend to the dog. I say that I can manage, that her condition is more important and take the heavy-as-a-TV dog into my arms and leave.

I walk with him to the bench. I sit down with him on the bench. We sit on the bench together. His Czech head on my Polish knees, I tap on his head lightly, pat him gently like he’s sleeping, I don’t want to cause a scene but I wonder what next. A cab won’t let him on, but to carry him home in my arms? He’s heavy but I have no choice. I try to carry him over my shoulder like you hold a child that’s about to be burped, with its head propped on your shoulder, but he’s too big. So I carry him so that he hangs across my arms, I carry him the way a soldier or a fireman would carry a wounded or a burned child. People turn, comment and ask what happened. I tell them that he was put to sleep during surgery and has a hard time waking up on account of his old age. Children ask his name, and I don’t know because I forgot to ask, and the Czech, on account of his old age, forgot to tell me, so I make it up—I say it’s Pepík, and the children behind me shout, “Pepík, Pepík wake up!” and more and more children join in.

So many that I’m at the head of a small procession. Traffic forms and curious drivers slow down, others honk . . . what a funeral he’s got, this Czech émigré from the village of Medlov-Králová.

Beautiful name this . . . Medlov-Králová.

I don’t know what next until I spot a TV repair shop. Enough of this procession, I walk in. A woman faints at the sight of me with the dog and the crowds amassing outside the shop window. A man emerges from the backroom, sees me, sees the dog, sees the woman on the floor and stops. And so it is that in a minute the TV repair shop turns into a cabinet of marionettes in which a visitor with my likeness lays down the dog, closes the door and revives the woman lying on the floor. As the woman gets off the floor, I try to explain what happened but she’s not listening. The woman is telling me to “Slow down, be quiet!” She is looking in the direction of the man who is still just standing there. Not wanting to lose any time, I look around searching for a large enough box. I see a large TV box, put the dog inside and look though the window to check if the coast is clear. It’s clear. I walk out. The box is heavy and as I’m trying to balance it on my shoulder it occurs to me to call a cab. I put the box down on the ground and walk back to the shop. The man is better now, he’s sitting down, and the woman who was lying on the floor is leaning over him. I ask for a cab number. They give it to me, I call a cab, walk out, and the box is gone.

Vanished.

I look right. I look left.

Gone.

“Where’s that box?”

Someone stands by the bus stop, someone who resembles a bus driver. Must be the bus driver. I ask him about the box. “I left it here a minute ago and now it’s gone.”

“That TV? The Gypsies took it. Drove by and took it. If that was yours then they stole it, thieves. I see everything, they steal everything.”

How to swallow this new development: the theft of a TV set in the shape of a dog. The earth spins on my account today. My heart rings like a bell. Bells are ringing in my ears. I can’t hear a thing. I ask the bus driver if he hears bells, but he can’t hear me. He shouts for me to speak louder because the church bells are tolling. Then something honks between one toll and the next and I turn around. A cab. The cab driver asks if it was me who just called. I say that it was, and try to picture quickly how I would tell the old Czech that his dog died. What face would I put on when he says okay, okay, but where is he? Should I tell him that his dog committed suicide or that he was stolen from me for the purpose of watching TV?

That’s why I ask the bus driver which direction they headed with that box. The bus driver points me in their direction and I ask what kind of car. He says what do you mean what kind of car? A strange-funeral-type-of-car.” I jump into the cab, tell the driver what happened and tell him that we have to undertake something like a car chase. The cab driver asks what car, I tell him, and we’re off.

We drive so fast that Jesus can barely hold on to the cross.

The cab driver is overwhelmed by the car chase and I even more, and to add to this, some idiotic tunes are coming from the radio. Tunes from the radio . . . the radio? No, it’s my phone. I don’t pick up. It has to be the old Czech. An intersection. Which way now? I give up. This is pointless. I want to get out but the cab driver tells me not to give up, that if one can rummage through the brain, a useful idea will be gained, for there is no shirt that can’t be ironed out, he tells me. That’s what his college-educated wife says, and he knows a place where they—Gypsies—are plentiful. Where they sit day and night, like they sit in the open-air museum Skansen, they sit all over Bergen-Belsen, and that his instinct has never led him astray. A sniper comes to mind, but not a cab driver, not in the least.

“Bergen-Belsen is a concentration camp!” I shout.

“Exactly.” says the driver, “Exactly, my dear sir, that’s where the Gypsies have pitched camp.”

“That’s a little far from Hamburg!”

He tells me not to worry. He’ll turn the meter off. “We’ll work it out in another way. Ready?” Ready. We’re moving fast, almost as fast as the wheels of history.

There, the driver stops at the gate amidst funeral-like cars. He wants to wait. He’s got an alibi. He says he’s worried about his car. I head for the camp alone and stop at the gate. A campfire burns inside the camp. Mothers stand around holding suckling babes, children play hide-and-seek and men are shuffling cards. I stand at the gate and they turn in my direction.

Sunset. I have the sun behind me, and a long shadow stretching out in front.

Mothers cease feeding, children leave their hiding places, and the men stop playing cards. My eyes search for the TV box and don’t find it. One of the men gets up, an important-looking man. He moves in my direction. I try to think what to say, maybe that if they don’t give me back my box with the dog in it, I’ll leave but I’ll come back tonight and set the whole place on fire.

I open my mouth but the Important-Looking-One beats me to it. In German that’s broken in several places, he says, “We welcome you, sir, in our threshold of woe. You are first German that decides to visit us. You are man who rushes to save the honor of the German people. Will you, in that case, take part in the invitation to supper together?”

Wait a minute, I say, I’ll be right back. I run to the driver and tell him to head back, that I’m staying, explaining to him that there are just things you can’t refuse.

The driver tells me to get out of there because it looks like something is brewing, he saw some commotion and he’s a little uneasy.

I can’t leave, I say. I’ve lived in Germany for over twenty years and it’s high time that I do more for this country than just complain about WWII— even if it’s one of my favorite pastimes.

The driver understands. He wishes for God to be with me, but I tell him it’s better that God be with him because in his profession God is more essential. He thanks me graciously for letting God stay with him and drives away. I head back to the camp.

They’re waiting for me by the campfire. I’m offered an honorary seat and flowers, men start playing, women start dancing, and children sit at my feet. Grilled food is passed around and I’m handed a plate with steaming hot meat. That half-chicken I had today was not much. I start eating, picking at the meat with my hands, just the way I like.

I sit and eat with the ones who chose to settle on the grounds of their literally extinguished ancestors.

I swallow the first bite, a peculiar taste. I ask what kind of meat, and the Important-Looking-One tells me that that’s not important, what’s important is that it tastes good. I glance at the grill, back at the meat, at the grill again, and at that exact moment things go black. My kinescope goes out.

I’m swallowing the old man’s Czech connection.

I feel weak, and I would have fainted if it wasn’t for some idiotic tune, my phone going off. I can’t pick up. My hands are greasy since I’m eating with my hands, the way I like. Two Polish women walk through the camp and one turns to the other and says, “See, a Gypsy. I told you.”

____________________________________________________________________

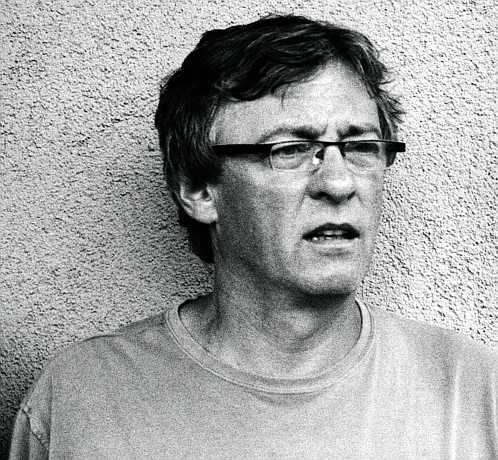

JANUSZ RUDNICKI (b. 1956) studied Slavic and German philology in Hamburg, where he has lived since 1983. He is a permanent contributor to the periodical Twórczość. He has published the volumes of prose: Life’s Like That (1992), Darn World (1994), There and Back Over the Rainbow (1997), and Potato Agony(2000). In 2007 W.A.B. published his My Wehrmacht, and Come On, Let’s Go! Rudnicki’s short story “The Sorrows of Idiot Augustus”, translated from the Polish by Jennifer Croft, was included in Best European Fiction 2012 by Dalkey Archive Press.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

BEATRICE SMIGASIEWICZ’s work has appeared in Denver Quarterly, Art Papers, Words Without Borders, and others. She’s currently pursuing a degree in Nonfiction Writing and Translation at the University of Iowa.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more about Janusz Rudnicki:

Author page at CULTURE.PL

About The Sorrows of Idiot Augustus on Literalab